|

White Sharks: New Jersey's Misunderstood Seasonal Visitors |

|

by Maggie Sager, Hourly Fisheries Technician

Bureau of Marine Fisheries

January 7, 2016

At the start of summer 2015, beach goers along the East Coast were once again reminded of the untamed nature of the ocean. A series of shark attacks in North Carolina led to a media frenzy and ignited concerns for vacationers, including here in New Jersey. While it is important to remember that we share the ocean with the marine species that call it home, it is also important to be aware of how unlikely a shark attack is. In fact, in 2014 there were no fatal attacks in the United States, and only six fatal unprovoked attacks worldwide (the average annual number for the past decade).

With over 400 species of shark officially recognized, the International Shark Attack File - a compilation of thousands of reported incidents ranging as far back as the 1500s - lists approximately 40 species implicated in unprovoked attacks on humans. Of these, around fifteen have fatal attacks attributed to them: less than 4% of all known shark species. Three of these, known collectively as the "Big Three," are responsible for the vast majority of attacks: the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier), and the bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas).

All of the Big Three are apex predators (at the top of the food chain not preyed upon by any other animal) and have evolved over hundreds of millions of years. They are large, inquisitive, and capable of inhabiting a wide range of environments, including the waters along New Jersey. While bull and tiger sharks seem to prefer the warmer sub-tropical waters along the southeastern seaboard, the white shark (commonly known as the Great White) is a frequent and common resident along the Jersey Shore, especially from mid-summer through early autumn.

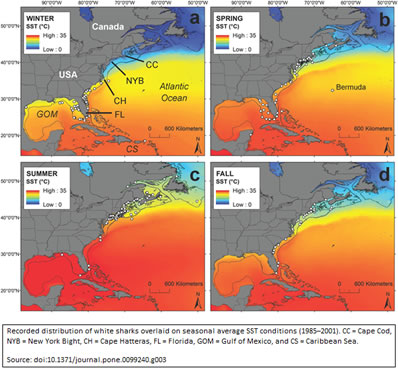

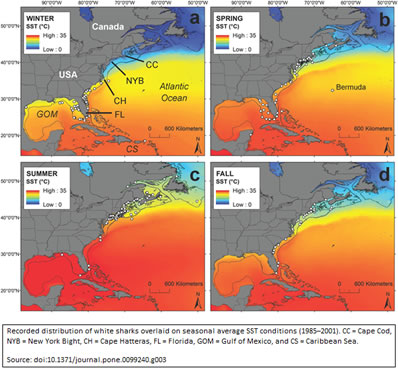

White sharks can tolerate colder water than many shark species (due to their ability to partially control their own body temperature), but seem to show a preference for a temperature range between 14° and 23° C (57.2° to 73.4° F). The wide continental shelf along the coast is similar to environments commonly associated with white shark nurseries; in fact, a 2014 study (Curtis et al.) supports this theory. Juveniles, particularly those born within the year, are most abundant in the region surrounding the New York Bight, the indentation extending from Cape May Inlet to Montauk Point on the eastern tip of Long Island.

|

Click to enlarge

|

Click to enlarge

|

Despite the size and environmental significance of white sharks, very little is known of their behavioral patterns. Data collection on white sharks for the northeastern United States only began in 2009 with a tagging program run from Cape Cod, by the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy.

Though it is acknowledged that juveniles feed on fish (particularly menhaden, hake, and bluefish) and adults primarily target pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) for their high fat content, Dr. Greg Skomal (one of the founding members of the Conservancy) confirmed that very little is known of specific white shark hunting strategies in this region.

Unlike well-studied populations, such as those in South Africa and the Farallon Islands, an active seal attack in the North Atlantic has only been witnessed a handful of times; the first-ever footage of a white shark predation off Monomoy Island, MA (captured by the Conservancy) made news headlines in early August, and showed breach behavior commonly seen in Pacific populations. As seal populations along the northeast continue to rebound, it seems likely that more white sharks will begin to congregate in the area, allowing for further study of their hunting behavior.

|

White sharks are ambush predators with excellent contrast vision; when hunting, attacks appear to occur from below and at great speed. In 2005, Martin et al. observed that white sharks near Seal Island, South Africa, attacked mostly around sunrise; one theory suggests that they are able to utilize the blinding effect of sunlight to their advantage while attacking from below and behind. The sharks of Seal Bay tended to show a preference for younger, clumsier seals, rather than more experienced and defensive adults. Erratic movements, such as those produced by the young seals, are known to attract sharks to potential prey sources. Furthermore, the sharp teeth and claws of a fighting seal can cause significant damage- the effort required to subdue an adult rarely outweighs the benefit.

So what factors go into an unprovoked attack on a human? George Burgess, Curator of the International Shark Attack File, spoke about the "perfect storm" of factors around the North Carolina attacks: warmer than usual water temperatures for the time of year, reduced rainfall (leading to a spike in salinity), and a banner season for baitfish (particularly menhaden). In his opinion, however, the culprits in the more serious attacks were likely bull sharks, with blacktip sharks and/or spinner sharks (neither of which are generally found in New Jersey's waters) accounting for the less severe cases.

|

Dr. Skomal echoed the sentiment that schooling baitfish are a potential precursor of increased shark activity. White sharks tend to congregate where large numbers of prey can be found, specifically seal colonies like the ones found off Cape Cod, South Africa, and the Farallon Islands. He also stressed the generally curious nature of these animals. White sharks have been known to "spy hop," peeking above the surface to get a view of their surroundings.

Mouthing objects is another commonly observed behavior: for a creature lacking hands, its teeth (which are full of nerve endings) must act as the primary tactile pathway. Test bites have been witnessed towards objects ranging from boat motors to floating seabirds. While this behavior lacks the speed and ferocity of a true attack, the strength of a fully-grown white shark (potentially up to 26 feet and 4000 pounds for the larger females), coupled with rows of serrated teeth specifically designed to grip and tear, can mean that serious (albeit unintentional) damage is done.

|

"Spy hopping" allows white sharks to examine their environment from a different perspective.

Click to enlarge

|

While sharks can pose a threat to humans, it is important to realize that we as a species are a far greater threat to them. Despite the annual worldwide average of six shark-related human fatalities, a shark attack has not occurred in New Jersey since 2013, and the last fatal attack in our waters was in 1926. Meanwhile, an estimated 100 million sharks are killed each year between sport fishing, bycatch, and commercial shark fishing. With a lifespan as long as the average human, white sharks do not reach sexual maturity until 26 to 33 years of age (for males and females respectively). Biologically, most shark species are incapable of quickly rebounding from any event that lowers the population. Although some, including white sharks, are protected by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), it could take decades for their populations to recover from a sharp decline.

In recent years, however, public sentiment has slowly begun to shift. Over the course of the 2015 summer, beach goers in Cape Cod worked to save multiple beached white sharks, and were successful at least once. Greater awareness of these animals continues to lead to greater tolerance, and one organization, OCEARCH, has created a website that allows the public to track sharks the research team has tagged.

In the second half of 2015, 16-foot white shark Mary Lee became a local celebrity as she made several trips up and down the New Jersey coast. Instead of avoiding the water, social media erupted with comments from people heading to the beach in hopes of a sighting. While such a positive reaction is a step in the right direction for shark populations globally, it is important to remember that they are wild animals; leaving them alone benefits both human and shark.

What can be done to minimize the risk of encountering a shark? Remaining aware of your surroundings is your best defense against a run-in with these super-predators. Never swim alone or after dark, and trust your instincts when in the water. Avoid areas where schools of baitfish may gather, such as sandbars, drop-offs, and murky areas near river mouths; similarly, avoid areas where people are actively fishing, as the splashing of hooked fish and traces of blood can lure predators to an easy meal.

Marine mammals should also be avoided: seals are a favorite source of prey for white sharks, and dolphins target some of the same prey preferred by sharks. If you do see a shark, or are told by a lifeguard to exit the water, do so in a calm, controlled manner. Splashing and panicking will only incite a shark's curiosity, and may provoke a bite.

Finally, remember to keep your relative risks in perspective: the United States Lifesaving Association estimates that over 100 deaths occur in the nation annually due to people being caught in rip currents. Despite what gets hyped by the media, most beach goers will never encounter a shark. Though they are most certainly aware of our presence in the water, the vast majority of sharks are content to avoid us and share the space. We simply aren't worth their effort.

References

Curtis TH, McCandless CT, Carlson JK, Skomal GB, Kohler NE, Natanson LJ, et al. 2014. Seasonal Distribution and Historic Trends in Abundance of White Sharks, Carcharodon carcharias, in the Western North Atlantic Ocean. PLoS ONE 9(6): e99240. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0099240

Global Shark Attack File. c1991-2014. The Shark Research Institute; [accessed 2015 July 31].

www.sharkattackfile.net.

International Shark Attack File. 2015. Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida; [accessed 2015 July 15].

www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/sharks/isaf/isaf.htm

Martin RA, Hammerschlag N, Collier RS, Fallows, C. 2005. Predatory behaviour of white sharks. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. UK 85: 1121-1135.

Shark Tracker. OCEARCH; [accessed 2015 December 8].

www.ocearch.org/#SharkTracker.

|