|

Connecting Waterfowl Behavior With Wintering Habitat Requirements In Coastal New Jersey

by

Jeremiah Heise, Graduate Student, Dept. of Wildlife Ecology, University of Delaware

Orrin Jones, Graduate Student, Dept. of Wildlife Ecology, University of Delaware

Paul Castelli, Wildlife Biologist, Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, and NJ DFW (ret.)

Christopher Williams, Associate Professor, Dept. of Wildlife Ecology, University of Delaware

|

|

February 15, 2013

A snowflake flits into your squinted eye and snaps you out of a frigid daze as a single black duck silently swings wide into your Spartan decoy rig. You wait until he is hovering over your furthest decoy and, sure of his being within range, you pull up and empty your chamber. Frustratingly, the duck flies away unscathed and you blame the miss on an improperly shouldered gun and an uncooperative trigger finger, both a result of being stiff from the cold.

The winters of 2009-10 and 2010-11 were two of the harshest on record, with snowfalls measured in feet rather than inches accompanied by bitter cold temperatures. A diehard hunter can appreciate what waterfowl are subject to during a given winter, but nonetheless end up exiting the marsh to a fully stoked fire, a hot cup of coffee, a warm meal, and a cozy bed.

|

What's on the menu for a black duck? Cold killifish with a side of iced snails. A brant? Frozen sea lettuce with a side of dead golf course grass. Black ducks and brant are exposed to the elements 24-7, and the food they eat must supply all the energy necessary for surviving the rigors of life in a winter salt marsh.

How much energy does a black duck or brant need to survive the winter in good condition so they can migrate north and breed? How many acres of habitat are needed to support a black duck or a brant? These are fundamental questions for waterfowl managers, yet the answers are elusive. With better answers to these questions, managers could set realistic population goals based on what is plausible and avoid population goals based on what might be desirable but not attainable.

Research into the energy dynamics of wintering waterfowl on the New Jersey coastal marshes began in 2006 with two collaborative projects, one focusing on American black ducks, and the other on Atlantic brant. Each of these projects had two phases: the first, completed by University of Delaware graduate students Dane Cramer (black ducks) and Zach Ladin (brant), encompassed diurnal (daytime) behavioral observations, radio telemetry to document habitat use, and quantified the energy density in preferred food items.

|

Black ducks conserve energy by resting in the sun on a cold winter's day in the saltmarsh.

Black ducks conserve energy by resting in the sun on a cold winter's day in the saltmarsh.

Click to enlarge |

The second phase of each project began in 2009 and focused on refining behavioral observations of each species by incorporating behavior during the night into 24-hour energy expenditure estimates.

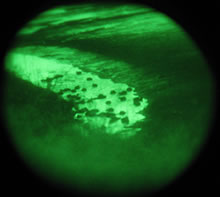

Black ducks feeding at night, viewed through a night vision scope used in this study.

Black ducks feeding at night, viewed through a night vision scope used in this study.

Click to enlarge |

Accurate estimates of behavior are important in calculating energy demands because there are tremendous differences in the amount of energy expended by birds exhibiting different behaviors. For example, flying requires 13 times the number of calories when compared to resting.

These research projects were a partnership between the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Edwin B. Forsythe and Cape May National Wildlife Refuges (NWR), Ducks Unlimited, Black Duck Joint Venture, Arctic Goose Joint Venture, Atlantic Flyway Council, New Jersey Waterfowlers Association, and the University of Delaware.

By observing black duck and brant behavior across all hours of the day, we were able to calculate the first 24-hour daily energy expenditure estimate for both species which was an important and novel contribution to the waterfowl research world. Observations were done from the third week of October 2009 and 2010, which coincides with the general arrival date of brant from Arctic breeding areas through the third week of February each winter. We established 44 observation locations from Atlantic City to Tuckerton, including both state Wildlife Management Areas and Forsythe NWR marshes. We collected data in areas both open and closed to hunting. Observations were conducted when the Coastal Zone hunting season was open and closed in both areas. We also collected weather, tide, daylight, and hunter presence data as possible explanatory variables in the behaviors that we observed. |

Observing birds throughout the entire 24-hour period was a daunting task. A single observation session was 6 hours in length and consisted of observing all birds within 200 meters of the observation location every 10 minutes. We conducted observations from permanent grassed blinds, pop-up blinds, and vehicles. Access to some locations relied on either boats or ATVs, which was especially challenging when travel to these locations was required during nighttime periods.

|

To fully account for the 24-hours of a day, observation sessions occurred across four defined times: 3:00-9:00am and 3:00-9:00pm to account for the respective morning and evening crepuscular (dawn and dusk) periods, or 9:00am-3:00pm and 9:00pm-3:00am to account for daytime and night time periods, respectively. Across both winters, we conducted over 30,000 observational scans inclusive of all present waterfowl. 11,616 observations included black duck behavior data and 5,862 observations included brant behavior data.

We found that both black ducks and Atlantic brant were active at night. Black ducks (see Figure 1) fed the most during the evening and night and flew less at night. Brant (see Figure 2) rested the most at night, fed the most during the day and evening, and flew the most in the morning. Additionally, we found that factors such as tidal height, hunting pressure, and weather influenced behavior across the 24-hour period. For example, black ducks and brant were more likely to use areas open to hunting at night than during the day, presumably to avoid hunting pressure during the day.

|

|

Previous studies of waterfowl energetic demand have assumed that behaviors were similar between night and day. However, the advances in night vision technology used in this study have allowed us to refine energetic demand through the 24-hour cycle during the important wintering period. The results of these projects will help managers further evaluate the habitat requirements and population dynamics of both species, with the goal of developing realistic, achievable habitat and population goals. Ultimately this should ensure sustainable populations that can support wildlife viewing and harvest into the foreseeable future.

RELATED PAGES

|