Seventh Periodic Report on Law Enforcement Professional Standards

- Posted on - 06/29/2021

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Background Information

- Methodology

- Findings

- Update on Selected Recommendations from OSC's 2018 and 2020 Reports

- Conclusions and Recommendations

Introduction

The Office of the State Comptroller (OSC) completed its seventh performance review of the New Jersey State Police (NJSP), a division within the Department of Law and Public Safety, and the oversight provided by the Office of Law Enforcement Professional Standards (OLEPS), as mandated by statute. OSC is statutorily obligated to conduct performance reviews to determine if NJSP is maintaining its commitment to non-discrimination, professionalism, and accountability while fulfilling its mission to serve and protect New Jersey and its residents. For this review, OSC examined NJSP’s Office of Professional Standards (OPS), and its policies, procedures, and processes for documenting, classifying, and investigating complaints made against troopers, and any discipline imposed. OSC also examined OLEPS’s oversight of NJSP on these matters.

In 1999, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) sued NJSP and the State of New Jersey for “intentional discrimination . . . in performing vehicle stops and post-stop enforcement actions and procedures, including searches, of African American motorists traveling on New Jersey Highways, including the New Jersey Turnpike.”[1] On December 30, 1999, the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey approved a Consent Decree that settled the litigation and committed the State to a series of reforms involving the management and operations of NJSP. The Consent Decree states that “state troopers may not rely to any degree on the race or national or ethnic origin of motorists in selecting vehicles for traffic stops and in deciding upon the scope and substance of post-stop actions, except where state troopers are on the look-out for a specific suspect who has been identified in part by his or her race or national or ethnic origin.”[2]

The Consent Decree required reforms in the following areas that were aimed at eliminating the racially-motivated vehicle stops carried out by NJSP: policy requirements and limitations on the use of race in law enforcement activities; traffic stop documentation; supervisory review of individual stops; supervisory review of patterns of conduct; investigations of misconduct allegations; training; auditing; and public reports. Pursuant to the Consent Decree, from 2000 to 2009, independent federal monitors issued bi-annual reports documenting NJSP’s progress in these areas, ultimately concluding that NJSP was fully compliant with the mandates of the agreement.[3]

In 2009, the court dissolved the Consent Decree on a joint motion by the State and DOJ. To ensure NJSP continued to comply with reforms initiated under the Consent Decree, the Legislature passed the Law Enforcement Professional Standards Act of 2009 (the Act), N.J.S.A. 52:17B-222, et seq. In view of the “strong public interest in perpetuating the quality and standards established under the consent decree,” the Act created OLEPS to “assume the functions that had been performed by the independent monitoring team.” N.J.S.A. 52:17B-223. OLEPS, which operates under the direct supervision of the Attorney General, performs such “administrative, investigative, policy and training oversight, and monitoring functions, as the Attorney General shall direct.” N.J.S.A. 52:17B-225. OLEPS is required to issue bi-annual reports that evaluate NJSP’s “compliance with relevant performance standards and procedures,” referred to as “Oversight Reports,” as well as semi-annual reports that include aggregate statistics on motor vehicle stops and misconduct investigations, referred to as “Aggregate Reports.” N.J.S.A. 52:17B-229, -235.[4] OLEPS issued its Fourteenth and Fifteenth Oversight Reports in February 2019 and May 2020, respectively.[5] OLEPS issued its Eighth Public Aggregate Misconduct Report in May 2020.[6]

OPS is the internal investigative office of NJSP responsible for investigating allegations of trooper misconduct and making recommendations to the NJSP Superintendent for the imposition of trooper discipline. OLEPS is responsible for reviewing, monitoring, and reporting on NJSP’s progress in these areas.

OSC, for its part, is required to conduct audits and reviews of NJSP and OLEPS to examine “stops, post-stop enforcement activities, internal affairs and discipline, decisions not to refer a trooper to internal affairs notwithstanding the existence of a complaint, and training.” N.J.S.A. 52:17B-336(a). For this review, OSC focused on internal affairs and trooper discipline. An effective internal affairs and discipline process is critical to eradicating and preventing the conduct that led to the Consent Order. In order to eliminate instances of racial profiling by a state police force, there must be clear and effective consequences for troopers who engage in such conduct. Accordingly, it is imperative for NJSP to have an effective and efficient internal affairs and disciplinary system to investigate allegations of police misconduct—including allegations of racial profiling—and impose appropriate discipline. Without effective internal review and disciplinary systems in place, misconduct by NJSP troopers would remain unchecked.

Through this review, OSC identified weaknesses in the implementation of NJSP’s and OLEPS’s policies and procedures while finding that those entities generally complied with the Act. Among other findings, OSC determined that OPS departed from governing NJSP policy by administratively closing five cases that should have been classified as performance issues. OLEPS was aware of this deviation from policy but did not take affirmative steps to correct it. Similarly, a process OPS used to administratively close some racial profiling and disparate treatments complaints ran counter to governing policy. OSC also determined that OLEPS is not using existing data to analyze race, gender, or rank and their influence, if any, on the imposition of discipline. With the goal of ensuring adherence to the mandates of the Act and the reforms achieved under the Consent Decree, OSC has made recommendations for improvement to address these and other findings discussed herein.

Background Information

A. NJSP Office of Professional Standards (OPS)

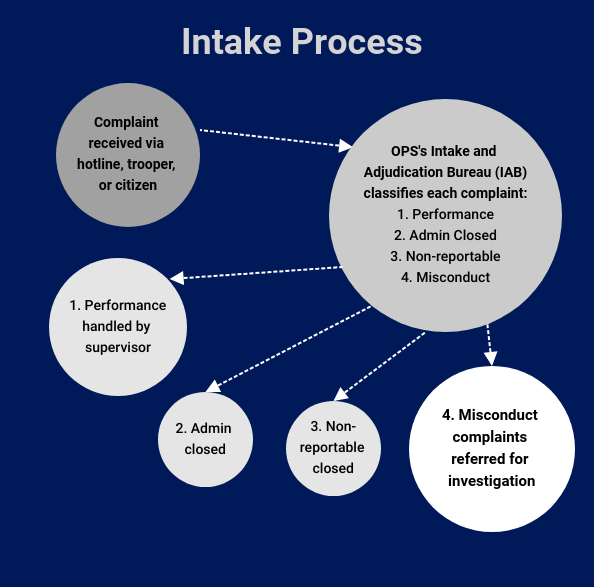

For this review, OSC examined the operations of OPS’s two internal affairs bureaus, the Intake & Adjudication Bureau (IAB) and the Internal Affairs Investigation Bureau (IAIB), and the relevant sub-departments contained within those bureaus. Specifically, OSC included in its review the Intake Unit and the Administrative Internal Proceedings Unit (AIPU), both within the IAB, and the three IAIB investigative units responsible for investigating misconduct complainants made against troopers.

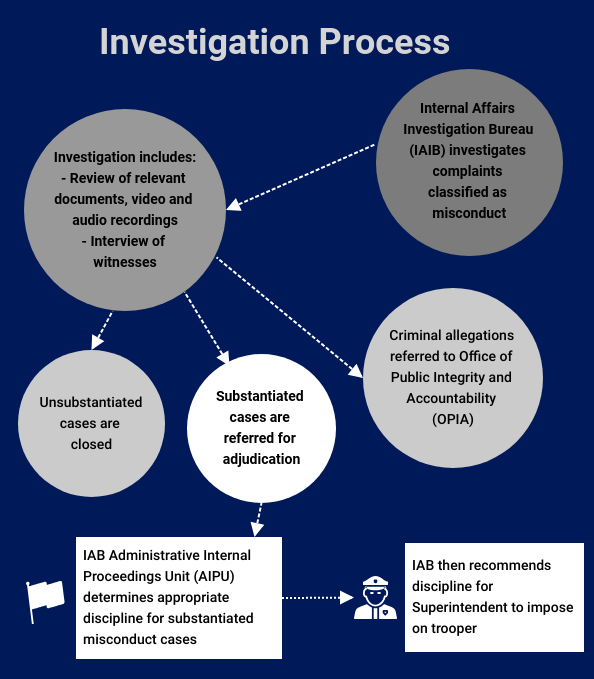

These bureaus and units, and their respective responsibilities in the handling of a complaint regarding a trooper’s conduct or performance, are discussed in greater detail herein. The below figures depict the process that a complaint regarding trooper performance or misconduct will generally follow.

Figure 1

Figure 2

1. Intake & Adjudication Bureau

OPS’s website provides instructions to the public on how to submit a complaint regarding NJSP trooper misconduct. A complaint may be made in person, physically mailed, emailed to an OPS inbox, or submitted via a hotline maintained by OPS.

The Intake Unit, within the IAB, is responsible for the receipt of all complaints against troopers and for the classification of those complaints. That classification determines the manner in which each complaint is handled. As set forth below, complaints are classified into one of three categories. The Intake Unit receives complaints either in writing, via email, or through the NJSP Complaint Hotline (Hotline). The manner in which the Intake Unit handles each of these complaints is governed by Standing Operating Procedure (SOP) B10, which details the internal investigative and disciplinary procedures, classification, processing, and adjudication of internal affairs matters.[7]

The operative version of SOP B10, which was approved by the Attorney General, has been in effect since July 2008. According to both NJSP and OLEPS, SOP B10 has been under review for a number of years. Proposed amendments have not yet been approved by the Attorney General.[8]

According to SOP B10, OPS must first determine if a particular complaint is a reportable[9] or non-reportable incident[10]. Non-reportable incidents are given a tracking number and closed out. Once OPS designates the complaint as a reportable incident, OPS forwards it to the subject trooper’s supervisors (Troop Command) for a recommendation on how the complaint should be classified. Pursuant to SOP B10, Troop Command is to make its recommendation within three business days of the receipt of the complaint from the Intake Unit and must include any available relevant documents utilized in its recommendation to the Intake Unit. Once the Intake Unit receives Troop Command’s recommendation and completes its own review, a complaint is classified as: (1) misconduct; (2) performance; or (3) administratively closed.

Misconduct classifications include, but are not limited to, allegations of racial profiling; disparate treatment; false arrest; excessive use of force; illegal or improper searches; or domestic violence. The Intake Unit forwards all misconduct complaints, except those handled as a misconduct short form[11], to IAIB for assignment to an investigator and commencement of an investigation. Any allegation of racial profiling or disparate treatment is also sent to the Office of Public Integrity and Accountability (OPIA) within the Attorney General’s Office for review of potential criminal conduct.

Performance classifications allege less serious inappropriate conduct. The Intake Unit classifies a complaint as performance-related for behavior that is non-disciplinary. Examples include allegations of attitude and demeanor, leaving a post, or failure to follow Mobile Video/Audio Recording (MVR) procedures. Once the Intake Unit classifies a complaint as performance-related, it forwards the case to the trooper’s supervisor for resolution. Per SOP B10, the supervisor must complete a Performance Incident Disposition Report (PIDR) on the allegations detailing any corrective actions, if needed, to resolve the minor infraction(s). A copy of the PIDR must be sent to OPS in order to close out the case.

Finally, the Intake Unit administratively closes a case if the initial evidence does not support a violation by the trooper.

The table below sets forth the number of complaints received and classified by the Intake Unit during the period of January 2018 through December 2020:

| Classification | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administratively Closed | 438 | 455 | 382 |

| Non-Reportable | 53 | 72 | 38 |

| Misconduct Short Form | 24 | 28 | 25 |

| Misconduct | 181 | 201 | 220 |

| Performance | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 702 | 758 | 665 |

SOP B10 also requires Intake Unit personnel handling Hotline complaints to (1) advise callers that the telephone line is recorded; (2) ensure callers are being treated with appropriate courtesy and respect; (3) not discourage callers from making complaints; and (4) obtain all necessary information about each complaint.

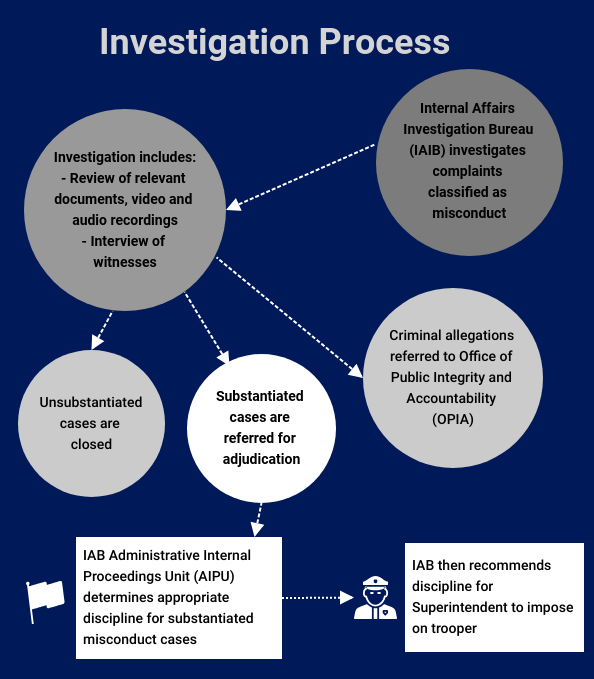

2. Internal Affairs Investigation Bureau

Once the Intake Unit has classified a complaint as misconduct, it sends an investigative file, which contains all documentation and evidence compiled during the classification process, to IAIB. IAIB then assigns the case to one of the three IAIB investigative unit heads who, in turn, assigns the case to an IAIB investigator. SOP B10 and the Operational Guide and Manual for Conducting Internal Investigations (Investigation Manual) provide that the assignment of a misconduct case to an investigator starts the 120-working day default deadline within which an investigator should complete an investigation.[12] A misconduct case is considered completed when the investigator submits it for supervisory review.

According to SOP B10 and the Investigation Manual, if an investigation will not be completed within 120 days, an extension must be applied for through the investigator’s chain of command. IAIB investigative unit supervisors track the 120-day time period for each investigation in their unit by providing a case accounting to the IAIB Bureau Chief. An investigator may request an extension of the 120-day rule for reasons such as a pending criminal prosecution or for a legal review by OPIA. The investigator is required to submit an extension form to the investigator’s supervisor, which must include a justification for the request. Extension requests are approved by the IAIB Chief and, when granted, toll the 120-day requirement. An OPS supervisor is then required to enter the extension request into IA-Pro, an internal NJSP computer program and database containing, among other things, data on internal affairs investigations and discipline of troopers.

The Investigation Manual requires that certain investigative steps be taken in each investigation, including the collection of all relevant physical evidence, documents, NJSP video, external surveillance video, police radio calls, photographs, internal NJSP reports, and external reports and records, but leaves the sequence of these steps to the discretion of each investigator. Investigators are also required to conduct interviews of the complainant, all fact witnesses, and the trooper against whom the complaint was made.

The investigator must inform the complainant of the existence of the investigation and give the complainant the opportunity to provide a statement. If the complainant cannot be reached by telephone or initially declines to be interviewed, the investigator must send a letter to the complainant advising that an investigation has begun and requesting that the complainant contact the investigator within ten days to schedule an interview. An investigation continues to its conclusion even if the complainant declines to provide a statement. The investigator also conducts interviews of any fact witnesses. All interviews are recorded to preserve the statements made and to aid in any later review of the matter by OLEPS and OPIA.

If, at any time during the course of the investigation, a question of criminality arises, OPS supervisory personnel contacts OLEPS and OPIA. If criminal charges are warranted, the administrative investigation is suspended pending the outcome of the criminal proceedings. If criminal charges are not warranted, the case is returned to OPS to continue with the administrative investigation.

When a case is returned to OPS, the investigator completes the investigation and prepares a final report, which includes detailed findings and conclusions. Pursuant to SOP B10 and the Investigation Manual, the investigator must make one of the following conclusions with regard to the allegation(s) in the complaint:

- Substantiated: a preponderance of the evidence shows that the trooper violated federal or state law, NJSP rules, regulations, SOPs, directives, or training.

- Unfounded: a preponderance of the evidence shows that the alleged misconduct did not occur.

- Exonerated: a preponderance of the evidence shows that the alleged conduct did occur, but it did not violate federal or state law, NJSP rules, regulations, SOPs, directives, or training.

- Insufficient Evidence: there is insufficient evidence to determine whether or not the alleged conduct occurred.

The Investigation Manual requires the final report to be subjected to three levels of supervisory review. At each level, the reviewer can either agree or disagree with some or all of the findings and conclusions and append any comments to the original report. Following the finalization of the investigation report, any substantiated allegations are forwarded to OPS’s AIPU for a recommendation concerning discipline, as discussed further below.

3. Disciplinary Process and Adjudication

Upon completion of an investigation, IAIB forwards the file on a substantiated allegation in a misconduct case to AIPU for further action. AIPU is responsible for recommending discipline to the NJSP Superintendent in cases in which an allegation has been substantiated. The SOP B10 requires OPS to consider the nature and scope of the misconduct and the information in the Management Awareness and Personnel Performance System (MAPPS)[13] when imposing discipline upon a trooper.

In practice, AIPU reviews the IAIB case file to ensure that there is sufficient evidence to support a finding of misconduct by the preponderance of the evidence standard, as would be required to prosecute a case at an administrative hearing. AIPU then examines a number of factors to determine the appropriate level of discipline including the nature of the misconduct, the trooper’s past disciplinary history, the trooper’s work performance, and comparable discipline imposed on other troopers for similar conduct. Additionally, AIPU reviews the trooper’s disciplinary history in IA-Pro and performance information on the trooper in MAPPS. To obtain comparable discipline cases for other troopers who committed similar misconduct, AIPU uses data in IA-Pro.

AIPU staff prepares a report for each substantiated case, which includes a statement of the allegations and conclusions, a concise disciplinary history of the subject trooper, detailed information about the trooper from MAPPS, the discipline imposed upon other troopers for similar misconduct, and AIPU’s recommended discipline. The report is ultimately sent to the NJSP Superintendent who, under SOP B10, is authorized to take disciplinary action against a trooper. The Superintendent considers the AIPU report in making a final disciplinary determination.

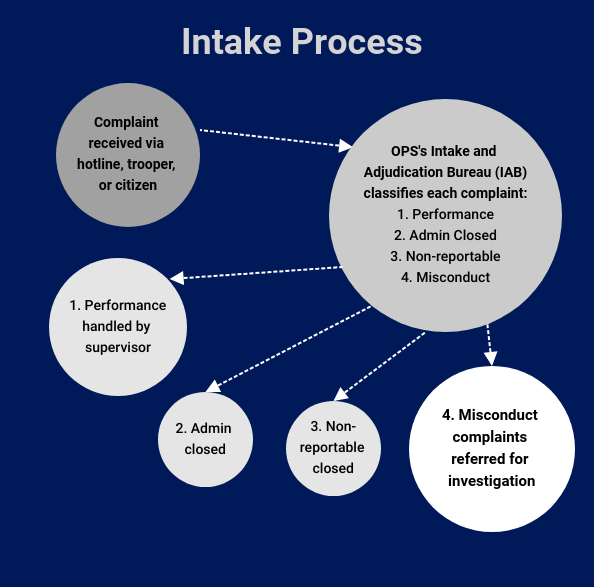

For this review, OSC examined the operations of OPS’s two internal affairs bureaus, the Intake & Adjudication Bureau (IAB) and the Internal Affairs Investigation Bureau (IAIB), and the relevant sub-departments contained within those bureaus. Specifically, OSC included in its review the Intake Unit and the Administrative Internal Proceedings Unit (AIPU), both within the IAB, and the three IAIB investigative units responsible for investigating misconduct complainants made against troopers.

These bureaus and units, and their respective responsibilities in the handling of a complaint regarding a trooper’s conduct or performance, are discussed in greater detail herein. The below figures depict the process that a complaint regarding trooper performance or misconduct will generally follow.

Figure 1

Figure 2

1. Intake & Adjudication Bureau

OPS’s website provides instructions to the public on how to submit a complaint regarding NJSP trooper misconduct. A complaint may be made in person, physically mailed, emailed to an OPS inbox, or submitted via a hotline maintained by OPS.

The Intake Unit, within the IAB, is responsible for the receipt of all complaints against troopers and for the classification of those complaints. That classification determines the manner in which each complaint is handled. As set forth below, complaints are classified into one of three categories. The Intake Unit receives complaints either in writing, via email, or through the NJSP Complaint Hotline (Hotline). The manner in which the Intake Unit handles each of these complaints is governed by Standing Operating Procedure (SOP) B10, which details the internal investigative and disciplinary procedures, classification, processing, and adjudication of internal affairs matters.[7]

The operative version of SOP B10, which was approved by the Attorney General, has been in effect since July 2008. According to both NJSP and OLEPS, SOP B10 has been under review for a number of years. Proposed amendments have not yet been approved by the Attorney General.[8]

According to SOP B10, OPS must first determine if a particular complaint is a reportable[9] or non-reportable incident[10]. Non-reportable incidents are given a tracking number and closed out. Once OPS designates the complaint as a reportable incident, OPS forwards it to the subject trooper’s supervisors (Troop Command) for a recommendation on how the complaint should be classified. Pursuant to SOP B10, Troop Command is to make its recommendation within three business days of the receipt of the complaint from the Intake Unit and must include any available relevant documents utilized in its recommendation to the Intake Unit. Once the Intake Unit receives Troop Command’s recommendation and completes its own review, a complaint is classified as: (1) misconduct; (2) performance; or (3) administratively closed.

Misconduct classifications include, but are not limited to, allegations of racial profiling; disparate treatment; false arrest; excessive use of force; illegal or improper searches; or domestic violence. The Intake Unit forwards all misconduct complaints, except those handled as a misconduct short form[11], to IAIB for assignment to an investigator and commencement of an investigation. Any allegation of racial profiling or disparate treatment is also sent to the Office of Public Integrity and Accountability (OPIA) within the Attorney General’s Office for review of potential criminal conduct.

Performance classifications allege less serious inappropriate conduct. The Intake Unit classifies a complaint as performance-related for behavior that is non-disciplinary. Examples include allegations of attitude and demeanor, leaving a post, or failure to follow Mobile Video/Audio Recording (MVR) procedures. Once the Intake Unit classifies a complaint as performance-related, it forwards the case to the trooper’s supervisor for resolution. Per SOP B10, the supervisor must complete a Performance Incident Disposition Report (PIDR) on the allegations detailing any corrective actions, if needed, to resolve the minor infraction(s). A copy of the PIDR must be sent to OPS in order to close out the case.

Finally, the Intake Unit administratively closes a case if the initial evidence does not support a violation by the trooper.

The table below sets forth the number of complaints received and classified by the Intake Unit during the period of January 2018 through December 2020:

| Classification | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administratively Closed | 438 | 455 | 382 |

| Non-Reportable | 53 | 72 | 38 |

| Misconduct Short Form | 24 | 28 | 25 |

| Misconduct | 181 | 201 | 220 |

| Performance | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 702 | 758 | 665 |

SOP B10 also requires Intake Unit personnel handling Hotline complaints to (1) advise callers that the telephone line is recorded; (2) ensure callers are being treated with appropriate courtesy and respect; (3) not discourage callers from making complaints; and (4) obtain all necessary information about each complaint.

2. Internal Affairs Investigation Bureau

Once the Intake Unit has classified a complaint as misconduct, it sends an investigative file, which contains all documentation and evidence compiled during the classification process, to IAIB. IAIB then assigns the case to one of the three IAIB investigative unit heads who, in turn, assigns the case to an IAIB investigator. SOP B10 and the Operational Guide and Manual for Conducting Internal Investigations (Investigation Manual) provide that the assignment of a misconduct case to an investigator starts the 120-working day default deadline within which an investigator should complete an investigation.[12] A misconduct case is considered completed when the investigator submits it for supervisory review.

According to SOP B10 and the Investigation Manual, if an investigation will not be completed within 120 days, an extension must be applied for through the investigator’s chain of command. IAIB investigative unit supervisors track the 120-day time period for each investigation in their unit by providing a case accounting to the IAIB Bureau Chief. An investigator may request an extension of the 120-day rule for reasons such as a pending criminal prosecution or for a legal review by OPIA. The investigator is required to submit an extension form to the investigator’s supervisor, which must include a justification for the request. Extension requests are approved by the IAIB Chief and, when granted, toll the 120-day requirement. An OPS supervisor is then required to enter the extension request into IA-Pro, an internal NJSP computer program and database containing, among other things, data on internal affairs investigations and discipline of troopers.

The Investigation Manual requires that certain investigative steps be taken in each investigation, including the collection of all relevant physical evidence, documents, NJSP video, external surveillance video, police radio calls, photographs, internal NJSP reports, and external reports and records, but leaves the sequence of these steps to the discretion of each investigator. Investigators are also required to conduct interviews of the complainant, all fact witnesses, and the trooper against whom the complaint was made.

The investigator must inform the complainant of the existence of the investigation and give the complainant the opportunity to provide a statement. If the complainant cannot be reached by telephone or initially declines to be interviewed, the investigator must send a letter to the complainant advising that an investigation has begun and requesting that the complainant contact the investigator within ten days to schedule an interview. An investigation continues to its conclusion even if the complainant declines to provide a statement. The investigator also conducts interviews of any fact witnesses. All interviews are recorded to preserve the statements made and to aid in any later review of the matter by OLEPS and OPIA.

If, at any time during the course of the investigation, a question of criminality arises, OPS supervisory personnel contacts OLEPS and OPIA. If criminal charges are warranted, the administrative investigation is suspended pending the outcome of the criminal proceedings. If criminal charges are not warranted, the case is returned to OPS to continue with the administrative investigation.

When a case is returned to OPS, the investigator completes the investigation and prepares a final report, which includes detailed findings and conclusions. Pursuant to SOP B10 and the Investigation Manual, the investigator must make one of the following conclusions with regard to the allegation(s) in the complaint:

- Substantiated: a preponderance of the evidence shows that the trooper violated federal or state law, NJSP rules, regulations, SOPs, directives, or training.

- Unfounded: a preponderance of the evidence shows that the alleged misconduct did not occur.

- Exonerated: a preponderance of the evidence shows that the alleged conduct did occur, but it did not violate federal or state law, NJSP rules, regulations, SOPs, directives, or training.

- Insufficient Evidence: there is insufficient evidence to determine whether or not the alleged conduct occurred.

The Investigation Manual requires the final report to be subjected to three levels of supervisory review. At each level, the reviewer can either agree or disagree with some or all of the findings and conclusions and append any comments to the original report. Following the finalization of the investigation report, any substantiated allegations are forwarded to OPS’s AIPU for a recommendation concerning discipline, as discussed further below.

3. Disciplinary Process and Adjudication

Upon completion of an investigation, IAIB forwards the file on a substantiated allegation in a misconduct case to AIPU for further action. AIPU is responsible for recommending discipline to the NJSP Superintendent in cases in which an allegation has been substantiated. The SOP B10 requires OPS to consider the nature and scope of the misconduct and the information in the Management Awareness and Personnel Performance System (MAPPS)[13] when imposing discipline upon a trooper.

In practice, AIPU reviews the IAIB case file to ensure that there is sufficient evidence to support a finding of misconduct by the preponderance of the evidence standard, as would be required to prosecute a case at an administrative hearing. AIPU then examines a number of factors to determine the appropriate level of discipline including the nature of the misconduct, the trooper’s past disciplinary history, the trooper’s work performance, and comparable discipline imposed on other troopers for similar conduct. Additionally, AIPU reviews the trooper’s disciplinary history in IA-Pro and performance information on the trooper in MAPPS. To obtain comparable discipline cases for other troopers who committed similar misconduct, AIPU uses data in IA-Pro.

AIPU staff prepares a report for each substantiated case, which includes a statement of the allegations and conclusions, a concise disciplinary history of the subject trooper, detailed information about the trooper from MAPPS, the discipline imposed upon other troopers for similar misconduct, and AIPU’s recommended discipline. The report is ultimately sent to the NJSP Superintendent who, under SOP B10, is authorized to take disciplinary action against a trooper. The Superintendent considers the AIPU report in making a final disciplinary determination.

B. Office of Law Enforcement Professional Standards and its Oversight Role

OLEPS’s oversight of NJSP includes, but is not limited to, the production of the semi-annual Aggregate Misconduct Reports, bi-annual Oversight Reports, and bi-annual audits of OPS.

The Act requires OLEPS to compile statistical data on complaints of misconduct on the part of NJSP troopers. This data and analysis are compiled and published in OLEPS’s Aggregate Misconduct Reports and Oversight Reports. In its Aggregate Misconduct Reports, OLEPS provides information concerning the number and types of complaints made against troopers in a given time period. The reports also address various trends in complaints against troopers, as well as the outcomes of those complaints. OLEPS’s Oversight Reports provide a summary of OLEPS’s audits of OPS for the time period covered.

OLEPS also conducts bi-annual audits of OPS that are, in part, intended to ensure that OPS is properly and thoroughly investigating misconduct allegations. The audits are also intended to assess the accuracy and consistency of information between IA-Pro and investigative case files, and to determine whether OPS is meeting the 120-day requirement for completing investigations.

As part of its audits, OLEPS reviews all cases closed by OPS in a six-month period involving the following categories: domestic violence, excessive force, racial profiling and disparate treatment, illegal/improper search, and false arrest. OLEPS also reviews a sample of the remaining misconduct, administratively closed, and performance cases closed by OPS. In conducting its review of these cases, OLEPS investigators review the OPS hardcopy case file, data from IA-Pro and, if needed, any video and audio recordings associated with the case.

OLEPS reviews each case to ensure the complaint was properly classified and all the required documentation is in the case file. For misconduct cases, OLEPS also examines whether OPS’s conclusions concerning each allegation are supported by a preponderance of the evidence.

During its audits, OLEPS evaluates whether investigations were performed within timeframes established by OLEPS. The goal in tracking these timeframes is to identify areas in which misconduct cases may be delayed in the investigative process. The timeframes include:

- Time between OPS’s receipt of complaint to assignment to an investigator – 25 working days;

- Time between investigation completion and completion of supervisory reviews – 40 working days;

- Time between completion of supervisory reviews and submission for legal sufficiency review – 30 working days.

Additionally, under SOP B10, OLEPS is required to conduct a weekly review of a representative number of recorded Hotline calls. The purpose of the Hotline reviews is to ensure OPS is (1) advising callers the telephone line is recorded; (2) treating callers with appropriate courtesy and respect; (3) not discouraging complainants from making complaints; and (4) obtaining all necessary information about each complaint. OSC found that OLEPS conducted these weekly reviews until March 9, 2020, when it was unable to continue such reviews due to the logistical challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. OLEPS plans to reinitiate the reviews once restrictions due to the pandemic are lifted.

OLEPS’s oversight of NJSP includes, but is not limited to, the production of the semi-annual Aggregate Misconduct Reports, bi-annual Oversight Reports, and bi-annual audits of OPS.

The Act requires OLEPS to compile statistical data on complaints of misconduct on the part of NJSP troopers. This data and analysis are compiled and published in OLEPS’s Aggregate Misconduct Reports and Oversight Reports. In its Aggregate Misconduct Reports, OLEPS provides information concerning the number and types of complaints made against troopers in a given time period. The reports also address various trends in complaints against troopers, as well as the outcomes of those complaints. OLEPS’s Oversight Reports provide a summary of OLEPS’s audits of OPS for the time period covered.

OLEPS also conducts bi-annual audits of OPS that are, in part, intended to ensure that OPS is properly and thoroughly investigating misconduct allegations. The audits are also intended to assess the accuracy and consistency of information between IA-Pro and investigative case files, and to determine whether OPS is meeting the 120-day requirement for completing investigations.

As part of its audits, OLEPS reviews all cases closed by OPS in a six-month period involving the following categories: domestic violence, excessive force, racial profiling and disparate treatment, illegal/improper search, and false arrest. OLEPS also reviews a sample of the remaining misconduct, administratively closed, and performance cases closed by OPS. In conducting its review of these cases, OLEPS investigators review the OPS hardcopy case file, data from IA-Pro and, if needed, any video and audio recordings associated with the case.

OLEPS reviews each case to ensure the complaint was properly classified and all the required documentation is in the case file. For misconduct cases, OLEPS also examines whether OPS’s conclusions concerning each allegation are supported by a preponderance of the evidence.

During its audits, OLEPS evaluates whether investigations were performed within timeframes established by OLEPS. The goal in tracking these timeframes is to identify areas in which misconduct cases may be delayed in the investigative process. The timeframes include:

- Time between OPS’s receipt of complaint to assignment to an investigator – 25 working days;

- Time between investigation completion and completion of supervisory reviews – 40 working days;

- Time between completion of supervisory reviews and submission for legal sufficiency review – 30 working days.

Additionally, under SOP B10, OLEPS is required to conduct a weekly review of a representative number of recorded Hotline calls. The purpose of the Hotline reviews is to ensure OPS is (1) advising callers the telephone line is recorded; (2) treating callers with appropriate courtesy and respect; (3) not discouraging complainants from making complaints; and (4) obtaining all necessary information about each complaint. OSC found that OLEPS conducted these weekly reviews until March 9, 2020, when it was unable to continue such reviews due to the logistical challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. OLEPS plans to reinitiate the reviews once restrictions due to the pandemic are lifted.

Methodology

For this report, OSC evaluated NJSP and OLEPS with regard to their responsibilities concerning trooper misconduct investigations and the imposition of trooper discipline as the result of such investigations. OSC reviewed OPS’s classification of complaints; the completeness and proper documentation in OPS’s case files; NJSP’s compliance with the requirement that misconduct investigations be completed within 120 days or if required extensions were obtained[14]; the accuracy of dates entered into IA-Pro as compared to dates included in the hard copy file; the thoroughness of OPS’s investigation of misconduct complaints; and whether NJSP considered the nature and scope of the misconduct as well as the trooper’s prior performance when imposing discipline upon a trooper. OSC also examined OLEPS’s oversight role to ensure OPS is meeting these and other performance standards.

To conduct its review, OSC studied the following:

- relevant NJSP rules, regulations, SOPs (including SOP B10), and OPS’s Investigation Manual;

- OPS’s internal complaint classification guide and a sample of complaints made on NJSP’s Hotline;

- a random and judgmental sample of 82 OPS investigative files closed during the review period, January 2018 through June 2020[15];

- a random sample of 16 OLEPS reviews of OPS investigative files from January 2018 through June 2019[16];

- relevant OLEPS’s operating procedures and internal memoranda directed to OPS;

- OLEPS audit reports issued in December 2018, June 2019, and December 2019, along with supporting documents;

- OPS’s annual reports, including draft reports that have not yet been released to the public.

OSC also interviewed various personnel within OPS, including but not limited to the IAB Chief, the IAIB Chief, and the AIPU Head. OSC investigators also observed the process by which a complaint of trooper misconduct is handled from intake through investigation and adjudication. OSC spoke with OLEPS personnel to discuss its oversight responsibilities regarding OPS’s handling of trooper performance complaints and the imposition of discipline. OSC discussed with OPS and OLEPS the status of selected recommendations made in OSC’s Fifth and Sixth Periodic Reports.[17] Finally, OSC interviewed police organizations and advocacy groups including civil rights groups, police unions, and others for additional perspective and information regarding the matters addressed in this report.

A draft of this report was sent to OLEPS and NJSP to provide them with an opportunity to comment on the issues identified during the course of our review. The written responses received were considered in preparing this final report and were incorporated herein where appropriate.

Findings

A. OSC’s Findings Related to the Performance of OPS’s Intake Unit and IAIB

To determine if OPS’s Intake Unit was properly classifying complaints against troopers, OSC sampled and reviewed 82 OPS cases closed during the review period. This sample included 37 cases that the Intake Unit had classified as administratively closed, 39 that had been classified as misconduct, two that had been classified as misconduct short form, and four classified as non-reportable. Of the sampled files reviewed, OSC found that, with the exception of five cases discussed in Section IV(A)(1) below, the Intake Unit had properly processed and documented those complaints. OSC also observed operations at the Hotline call center and listened to recorded conversations between complainants and Intake Unit personnel. OSC’s review found that the Intake Unit dealt with callers in a professional and courteous manner and obtained pertinent information from them.

To establish whether IAIB is conducting thorough misconduct investigations, OSC reviewed the 39 misconduct cases to ensure they contained all the required investigative documents and evidentiary material. OSC also examined whether IAIB’s determinations that allegations were either substantiated, unfounded, exonerated, or had insufficient evidence were supported. OSC reviewed all relevant documentation and evidence contained in each of those files, including audiotaped statements of the complainant(s), the trooper that was the subject of the complaint, and any witnesses; MVR and body worn camera videos of the incident; any prior disciplinary history of the trooper; and any references to discipline imposed in similar cases.

OSC’s review of the 39 completed misconduct investigations found that the evidence supported the findings and conclusions in each of the cases. Based upon available documents, it also appeared to OSC that discipline imposed was consistently meted out. OSC, however, was not able to review details of the prior offenses captured in the disciplinary lookback for the charged offenses.[18]

Notwithstanding OSC’s determination that the Intake Bureau and IAIB were generally compliant with governing procedures for classification and discipline, OSC identified deviations from established policy. Specifically, OSC found that OPS failed to follow SOP B10 in three ways, each of which is separately discussed below. OSC also found that the NJSP website instructions for filing a complaint with OPS required certain improvements.

1. OPS Unilaterally Instituted a Change in the Process for Classifying Complaints by Eliminating the Performance Classification.

OSC’s review of OPS’s Intake Unit included an examination of 37 cases that the Intake Unit had classified as administratively closed. OSC determined that five of these cases should have been classified as performance cases instead of administratively closed according to the criteria noted in SOP B10. When OSC asked OPS personnel why the cases were closed administratively, OSC was told that OPS had ceased using the performance classification several years earlier. As discussed above, the performance classification is used for complaints involving less serious inappropriate conduct or behavior that is non-disciplinary in nature. It could also include instances when the trooper’s demeanor is unprofessional or rude during a motor vehicle stop.

OPS personnel could not provide OSC any documentation on how and why this change to the classification process was implemented. OPS personnel provided OSC with a blank copy of what they referred to as an “unofficial” NJSP OPS Incident Classification form, which is currently being used. This Incident Classification form did not list performance as one of the classification options for a complaint. Instead, in addition to the misconduct and administratively closed classifications, the form listed a new classification, “Administratively Closed With Other Action Taken.” This new classification is not authorized by, or mentioned in, SOP B10. In addition, OPS personnel advised there is no SOP or Operations Instruction governing the elimination of the performance classification or the newly created administratively closed classification.

OPS should not have implemented this change to the classification process before the necessary amendments were made to the governing SOP and approved by the Attorney General. Written policies and procedures are designed to ensure consistency, accountability, and transparency. In fact, the Act specifically mandates that any changes to NJSP rules, regulations, standing operating procedures, and operations instructions relating to the consent decree be approved in writing by the Attorney General prior to issuance or adoption by the superintendent. N.J.S.A. 52:17B-223(e). OPS failed to secure the necessary approvals before unilaterally eliminating the performance classification, in clear violation of the Act.

By not following the clear mandate of the Act, NJSP has created a weakness in the very system designed to ensure professional conduct on the part of troopers. By eliminating the performance classification and administratively closing a complaint, it is possible that some issues regarding a trooper’s performance may not be addressed and documented as thoroughly. Although the effect of this decision may have only reached minor performance issues, leaving even those unaddressed can lead troopers to develop poor work habits that can lead to more serious issues. Under SOP B10, the classification of a complaint as performance-related required both OPS and the trooper’s supervisors to take some action and to document it in a PIDR.

Accordingly, OSC recommends that NJSP immediately reinstate the use of the performance classification, and further assess whether discontinuing its use is appropriate. Should a change in policy occur regarding the use of the performance classification, NJSP should receive approval of that change from both OLEPS and the Attorney General. Careful consideration should be given to whether the elimination or modification of this category would undermine effective supervision and documentation of trooper conduct.

In its written response to a discussion draft of this report, NJSP disagreed with this recommendation, and stated that it “declines to discontinue its changes to the performance classification process.” NJSP explained that the performance classification process “was changed in an effort to more quickly resolve non-disciplinary complaints,” and that the changed process “operates to better allocate investigative resources towards disciplinary complaints so that investigators are assigned those complaints rather than minor, non-disciplinary matters.” NJSP also described that new process as “a pilot program” and explained that the process has “been recognized, and continually analyzed and reviewed by OLEPS in each of its audits since 2018 with positive results.”

OSC nonetheless maintains its recommendation, which is aimed at remedying NJSP’s process failure to follow both the mandates of the Act and its own policies. Regardless of the ultimate merits of changing the performance classification process, NJSP is required to comply with the Act to change the processes in question, and should have done so in order to ensure consistency, accountability, and transparency in its written policies and procedures. In its response to the draft report, NJSP acknowledged that moving forward it “will evaluate its process for the development and implementation of new pilot programs and work with OLEPS and OPIA to implement a more documented approval process as OPS continues to work to increase its operational efficiencies.” NJSP also stated that “revisions to SOP B10 are under review and are expected to be finalized in the near future.”

2. OPS Established a New Process to Administratively Close Some Racial Profiling and Disparate Treatment Complaints Without Investigation by IAIB Investigators and Without Review by the Attorney General’s Office

According to SOP B10 and the Investigation Manual, allegations of racial profiling and disparate treatment by troopers are classified as misconduct and sent to IAIB for investigation. As part of IAIB’s investigation, these complaints are sent to OPIA for review to determine if criminal prosecution is warranted. This review is referred to by OPS as a legal review. If OPIA declines to prosecute, it will notify IAIB to continue with the administrative investigation.

OSC’s review revealed, however, that OPS, with the concurrence of OLEPS and OPIA, instituted a new process in October 2019 on a trial basis for administratively closing certain racial profiling and disparate treatment complaints. Specifically, OPIA, OLEPS, and OPS agreed that OPS could close some racial profiling and disparate treatment cases if certain agreed upon criteria were met.[19] Under this new process, OPS may close the complaint if:

- There is a complete video and audio recording of the incident that gave rise to the allegation of racial profiling or disparate treatment;

- The Intake Unit reviews the recordings and any other available documentation and ensures the video and audio is free from any indication of race-based statements, actions, or any other discriminatory practice/behavior;

- The trooper does not have any current or past allegations of discrimination made against them;

- If the incident involved a motor vehicle stop, the Intake Unit has conducted an analysis of the trooper’s motor vehicle stop history, which demonstrated that there were no statistical disparities relevant to the driver/occupant’s race and/or gender; and

- The Intake Unit has contacted the complainant.

Under the new process, all the information regarding the incident and evidence gathered by the Intake Unit are documented on an intake review form that is sent to OPIA, along with a list of all available documentation, for review.[20] Importantly, if a complaint is administratively closed under this new procedure, there is neither an investigation by IAIB nor a legal review by OPIA. This new process seemingly deviates from the requirements of SOP B10 and was never approved in writing by the Attorney General as required by N.J.S.A. 52:17B-223(e).

OSC was told by OLEPS, OPS, and OPIA that the justification for implementing this new process was to streamline the review of some racial profiling and disparate treatment cases that did not warrant a full investigation. OLEPS also advised OSC that any racial profiling or disparate treatment cases administratively closed by OPS would be reviewed as part of OLEPS’s bi-annual audits.

OPS and OPIA advised OSC that, although this new process for closing cases is still available to OPS, it is no longer being used.[21] At present, according to OPS, all racial profiling and disparate treatment complaints are being sent to IAIB for investigation and legal review by OPIA. Should this process resume, OSC is concerned that the closing of racial profiling and disparate treatments complaints without further investigation may lead to valid complaints being overlooked.

OSC recommends that NJSP, in consultation with the Attorney General, continue to refrain from its practice of administratively closing racial profiling and disparate treatment complaints without further investigation when certain criteria are satisfied, and further assess whether such a practice is appropriate. Any changes to the current practices concerning the treatment of racial profiling and disparate treatment complaints should be formalized in SOP B10 after approval by the Attorney General. Careful consideration should be given to whether this proposed practice of administratively closing certain racial profiling complaints would undermine the Attorney General’s oversight of NJSP in the area of racial profiling. In its written response to a discussion draft of this report, NJSP stated that it “agrees that if the pilot project is to continue, it will be included in the revised SOP B10, and any matters evaluated using the procedure described in the pilot project will still be subject to review by both OLEPS and OPIA.”

3. Investigators Do Not Always Make or Memorialize Requests for an Extension of the 120-Day Requirement

To determine if OPS is complying with the requirement that misconduct investigations be completed within 120 days,[22] OSC reviewed 39 completed misconduct investigations. OSC calculated the length of an investigation using the date the case was assigned to an investigator and the date the investigation was completed as recorded in the hardcopy case file.[23]

OSC’s review found that 12 of the 39 misconduct investigations were not completed within 120 days, representing 30.8 percent of the cases. On average, it took 101.9 working days from assignment to completion of the investigation. OLEPS’s most recent bi-annual audit calculated that 25.76 percent of the cases it reviewed took longer than 120 days to complete. OLEPS found that, on average, it took 105.5 working days for an IAIB investigator to complete a misconduct investigation. Both OSC’s review and OLEPS’s audit show that while there is room for improvement, OPS has made improvements in reducing the number of cases exceeding the 120-day requirement.

OSC also compared dates in IA-Pro to dates entered in hardcopy case files pertaining to various investigative activities. For example, OSC compared the date a case was assigned to an investigator as shown in IA-Pro to the date reflected in the hardcopy case file. OSC’s review found only seven instances in which the dates did not match and most were only one or two days off. OLEPS also examines the differences between dates entered into IA-Pro versus the dates in case files to see if they match. OLEPS, in its most recent audit of OPS, found three instances in which there was a difference between the dates a misconduct case was assigned to an investigator in IA-Pro and the date recorded in the hardcopy case file. OSC’s review concludes that while there is opportunity for improvement, OPS has improved its performance in ensuring the data in IA-Pro matches that reflected in the hardcopy case file.

If a case cannot be completed within 120 days, the investigator must make a request for extension beyond the 120-day requirement. OSC’s case review of 39 files found that of 12 misconduct cases that exceeded the 120-day requirement, three lacked the required request for an extension.

In completing the extension request, an investigator must provide an explanation regarding why the 120-day requirement cannot be met. The explanation contained in the extension request is a valuable tool for OPS in identifying possible systemic issues that may be causing delays in completing investigations. Furthermore, the extension requests hold the investigators accountable for completing their caseload in a timely manner. The request also assists OLEPS and OSC in understanding why delays occurred when conducting their audits and reviews of OPS. Reasons for not meeting the 120-day deadline can include caseload, witness unavailability, and changing investigators. OSC was also told that, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to shift investigators to non-IAIB matters, one investigative unit experienced a backlog of investigations.

The timely resolution of misconduct investigations enables prompt intervention designed to avoid the recurrence of any misconduct and satisfy the public that transgressions by police officers are addressed appropriately. Equally important, troopers who are the subject of misconduct investigations have an interest in the timely resolution of complaints against them. OPS staff noted that trooper promotions or transfers may be delayed until a misconduct investigation has been resolved. Additionally, complainants and the public will have greater confidence in the investigative process if the 120-day rule is adhered to unless extensions are requested. The consistent use of extension requests when appropriate strengthens that public trust by providing a reasonable basis for delays in the investigative process.

OSC recommends that IAIB investigative unit heads ensure IAIB investigators request an extension of the 120-day requirement to complete an investigation when an investigation will exceed such time frame. In its written response to a discussion draft of this report, NJSP agreed with this recommendation and advised that “OPS will continue to work to further improve in this area in accordance with SOP B10 and the Internal Affairs Policy and Procedures Manual (IAPP).”

4. The NJSP Website’s Online Complaint Submission Instructions Require Improvements

NJSP’s website provides information to the public on how to file a complaint against a trooper.[24] OSC has identified two problematic issues with the website instructions that should be improved: the lack of an email address for complaint submissions and the inclusion of a website disclaimer that threatens prosecution and civil action against those who submit frivolous complaints.

a. Email Address for Complaints

Until recently, the only means to file such a complaint was either calling the toll-free Hotline, mailing a letter, or making an in-person complaint. During the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person complaints were no longer being accepted, so the only manner in which complaints could be submitted by the public was via the Hotline or mail. The absence of an email address on the website appears to be a missed opportunity to receive complaints given how much communication is done by email both within and outside of government.

During a February 16, 2021 interview with OPS Intake Unit personnel, OSC learned that an email address did, in fact, exist to which complaints regarding trooper misconduct could be emailed, but that the email address had not yet been made available to the public on the NJSP website.

OSC recommends that NJSP provide an email address for OPS so members of the public can file online complaints, and confirms that OPS has now complied with this recommendation. On February 22, 2021, just over a week after OSC raised the issue with OPS personnel, OSC was informed that NJSP had updated the website to include the email address for filing complaints. OSC was further advised by the Intake and Adjudication Bureau Chief that, as a result of publishing the email address on the website, there has been an increase in complaints. In its response to a discussion draft of this report, NJSP stated that it agreed with OSC’s recommendation and confirmed that after OSC brought this issue to OPS’s attention, the email address was added to NJSP’s website.

b. Website Disclaimer

Although the NJSP website properly provided a description of the complaint submission process and the corrective action that may result from a complaint, it also contained the following caveat in bolded, italicized text: “We take your complaint seriously. However, if a complaint is found to be fabricated and maliciously pursued, the complainant may be subject to criminal prosecution and/or civil proceedings.”[25]

This warning and the threat of prosecution it provides may have had an improper chilling effect on complaints submitted to OPS. And it is unusual to include such a warning in instructions for a law enforcement misconduct tip hotline.[26]

OSC accordingly recommends that NJSP remove disclaimers from its complaint submission instructions that threaten criminal prosecution and/or civil proceedings against complainants. In its written response to the discussion draft of this report, NJSP agreed with OSC’s recommendation and advised that “[a]fter a review of internal affairs best practices, OPS removed the disclaimer from the website effective June 3, 2021.”[27]

To determine if OPS’s Intake Unit was properly classifying complaints against troopers, OSC sampled and reviewed 82 OPS cases closed during the review period. This sample included 37 cases that the Intake Unit had classified as administratively closed, 39 that had been classified as misconduct, two that had been classified as misconduct short form, and four classified as non-reportable. Of the sampled files reviewed, OSC found that, with the exception of five cases discussed in Section IV(A)(1) below, the Intake Unit had properly processed and documented those complaints. OSC also observed operations at the Hotline call center and listened to recorded conversations between complainants and Intake Unit personnel. OSC’s review found that the Intake Unit dealt with callers in a professional and courteous manner and obtained pertinent information from them.

To establish whether IAIB is conducting thorough misconduct investigations, OSC reviewed the 39 misconduct cases to ensure they contained all the required investigative documents and evidentiary material. OSC also examined whether IAIB’s determinations that allegations were either substantiated, unfounded, exonerated, or had insufficient evidence were supported. OSC reviewed all relevant documentation and evidence contained in each of those files, including audiotaped statements of the complainant(s), the trooper that was the subject of the complaint, and any witnesses; MVR and body worn camera videos of the incident; any prior disciplinary history of the trooper; and any references to discipline imposed in similar cases.

OSC’s review of the 39 completed misconduct investigations found that the evidence supported the findings and conclusions in each of the cases. Based upon available documents, it also appeared to OSC that discipline imposed was consistently meted out. OSC, however, was not able to review details of the prior offenses captured in the disciplinary lookback for the charged offenses.[18]

Notwithstanding OSC’s determination that the Intake Bureau and IAIB were generally compliant with governing procedures for classification and discipline, OSC identified deviations from established policy. Specifically, OSC found that OPS failed to follow SOP B10 in three ways, each of which is separately discussed below. OSC also found that the NJSP website instructions for filing a complaint with OPS required certain improvements.

1. OPS Unilaterally Instituted a Change in the Process for Classifying Complaints by Eliminating the Performance Classification.

OSC’s review of OPS’s Intake Unit included an examination of 37 cases that the Intake Unit had classified as administratively closed. OSC determined that five of these cases should have been classified as performance cases instead of administratively closed according to the criteria noted in SOP B10. When OSC asked OPS personnel why the cases were closed administratively, OSC was told that OPS had ceased using the performance classification several years earlier. As discussed above, the performance classification is used for complaints involving less serious inappropriate conduct or behavior that is non-disciplinary in nature. It could also include instances when the trooper’s demeanor is unprofessional or rude during a motor vehicle stop.

OPS personnel could not provide OSC any documentation on how and why this change to the classification process was implemented. OPS personnel provided OSC with a blank copy of what they referred to as an “unofficial” NJSP OPS Incident Classification form, which is currently being used. This Incident Classification form did not list performance as one of the classification options for a complaint. Instead, in addition to the misconduct and administratively closed classifications, the form listed a new classification, “Administratively Closed With Other Action Taken.” This new classification is not authorized by, or mentioned in, SOP B10. In addition, OPS personnel advised there is no SOP or Operations Instruction governing the elimination of the performance classification or the newly created administratively closed classification.

OPS should not have implemented this change to the classification process before the necessary amendments were made to the governing SOP and approved by the Attorney General. Written policies and procedures are designed to ensure consistency, accountability, and transparency. In fact, the Act specifically mandates that any changes to NJSP rules, regulations, standing operating procedures, and operations instructions relating to the consent decree be approved in writing by the Attorney General prior to issuance or adoption by the superintendent. N.J.S.A. 52:17B-223(e). OPS failed to secure the necessary approvals before unilaterally eliminating the performance classification, in clear violation of the Act.

By not following the clear mandate of the Act, NJSP has created a weakness in the very system designed to ensure professional conduct on the part of troopers. By eliminating the performance classification and administratively closing a complaint, it is possible that some issues regarding a trooper’s performance may not be addressed and documented as thoroughly. Although the effect of this decision may have only reached minor performance issues, leaving even those unaddressed can lead troopers to develop poor work habits that can lead to more serious issues. Under SOP B10, the classification of a complaint as performance-related required both OPS and the trooper’s supervisors to take some action and to document it in a PIDR.

Accordingly, OSC recommends that NJSP immediately reinstate the use of the performance classification, and further assess whether discontinuing its use is appropriate. Should a change in policy occur regarding the use of the performance classification, NJSP should receive approval of that change from both OLEPS and the Attorney General. Careful consideration should be given to whether the elimination or modification of this category would undermine effective supervision and documentation of trooper conduct.

In its written response to a discussion draft of this report, NJSP disagreed with this recommendation, and stated that it “declines to discontinue its changes to the performance classification process.” NJSP explained that the performance classification process “was changed in an effort to more quickly resolve non-disciplinary complaints,” and that the changed process “operates to better allocate investigative resources towards disciplinary complaints so that investigators are assigned those complaints rather than minor, non-disciplinary matters.” NJSP also described that new process as “a pilot program” and explained that the process has “been recognized, and continually analyzed and reviewed by OLEPS in each of its audits since 2018 with positive results.”

OSC nonetheless maintains its recommendation, which is aimed at remedying NJSP’s process failure to follow both the mandates of the Act and its own policies. Regardless of the ultimate merits of changing the performance classification process, NJSP is required to comply with the Act to change the processes in question, and should have done so in order to ensure consistency, accountability, and transparency in its written policies and procedures. In its response to the draft report, NJSP acknowledged that moving forward it “will evaluate its process for the development and implementation of new pilot programs and work with OLEPS and OPIA to implement a more documented approval process as OPS continues to work to increase its operational efficiencies.” NJSP also stated that “revisions to SOP B10 are under review and are expected to be finalized in the near future.”

2. OPS Established a New Process to Administratively Close Some Racial Profiling and Disparate Treatment Complaints Without Investigation by IAIB Investigators and Without Review by the Attorney General’s Office

According to SOP B10 and the Investigation Manual, allegations of racial profiling and disparate treatment by troopers are classified as misconduct and sent to IAIB for investigation. As part of IAIB’s investigation, these complaints are sent to OPIA for review to determine if criminal prosecution is warranted. This review is referred to by OPS as a legal review. If OPIA declines to prosecute, it will notify IAIB to continue with the administrative investigation.

OSC’s review revealed, however, that OPS, with the concurrence of OLEPS and OPIA, instituted a new process in October 2019 on a trial basis for administratively closing certain racial profiling and disparate treatment complaints. Specifically, OPIA, OLEPS, and OPS agreed that OPS could close some racial profiling and disparate treatment cases if certain agreed upon criteria were met.[19] Under this new process, OPS may close the complaint if:

- There is a complete video and audio recording of the incident that gave rise to the allegation of racial profiling or disparate treatment;

- The Intake Unit reviews the recordings and any other available documentation and ensures the video and audio is free from any indication of race-based statements, actions, or any other discriminatory practice/behavior;

- The trooper does not have any current or past allegations of discrimination made against them;

- If the incident involved a motor vehicle stop, the Intake Unit has conducted an analysis of the trooper’s motor vehicle stop history, which demonstrated that there were no statistical disparities relevant to the driver/occupant’s race and/or gender; and

- The Intake Unit has contacted the complainant.

Under the new process, all the information regarding the incident and evidence gathered by the Intake Unit are documented on an intake review form that is sent to OPIA, along with a list of all available documentation, for review.[20] Importantly, if a complaint is administratively closed under this new procedure, there is neither an investigation by IAIB nor a legal review by OPIA. This new process seemingly deviates from the requirements of SOP B10 and was never approved in writing by the Attorney General as required by N.J.S.A. 52:17B-223(e).

OSC was told by OLEPS, OPS, and OPIA that the justification for implementing this new process was to streamline the review of some racial profiling and disparate treatment cases that did not warrant a full investigation. OLEPS also advised OSC that any racial profiling or disparate treatment cases administratively closed by OPS would be reviewed as part of OLEPS’s bi-annual audits.

OPS and OPIA advised OSC that, although this new process for closing cases is still available to OPS, it is no longer being used.[21] At present, according to OPS, all racial profiling and disparate treatment complaints are being sent to IAIB for investigation and legal review by OPIA. Should this process resume, OSC is concerned that the closing of racial profiling and disparate treatments complaints without further investigation may lead to valid complaints being overlooked.

OSC recommends that NJSP, in consultation with the Attorney General, continue to refrain from its practice of administratively closing racial profiling and disparate treatment complaints without further investigation when certain criteria are satisfied, and further assess whether such a practice is appropriate. Any changes to the current practices concerning the treatment of racial profiling and disparate treatment complaints should be formalized in SOP B10 after approval by the Attorney General. Careful consideration should be given to whether this proposed practice of administratively closing certain racial profiling complaints would undermine the Attorney General’s oversight of NJSP in the area of racial profiling. In its written response to a discussion draft of this report, NJSP stated that it “agrees that if the pilot project is to continue, it will be included in the revised SOP B10, and any matters evaluated using the procedure described in the pilot project will still be subject to review by both OLEPS and OPIA.”

3. Investigators Do Not Always Make or Memorialize Requests for an Extension of the 120-Day Requirement

To determine if OPS is complying with the requirement that misconduct investigations be completed within 120 days,[22] OSC reviewed 39 completed misconduct investigations. OSC calculated the length of an investigation using the date the case was assigned to an investigator and the date the investigation was completed as recorded in the hardcopy case file.[23]

OSC’s review found that 12 of the 39 misconduct investigations were not completed within 120 days, representing 30.8 percent of the cases. On average, it took 101.9 working days from assignment to completion of the investigation. OLEPS’s most recent bi-annual audit calculated that 25.76 percent of the cases it reviewed took longer than 120 days to complete. OLEPS found that, on average, it took 105.5 working days for an IAIB investigator to complete a misconduct investigation. Both OSC’s review and OLEPS’s audit show that while there is room for improvement, OPS has made improvements in reducing the number of cases exceeding the 120-day requirement.

OSC also compared dates in IA-Pro to dates entered in hardcopy case files pertaining to various investigative activities. For example, OSC compared the date a case was assigned to an investigator as shown in IA-Pro to the date reflected in the hardcopy case file. OSC’s review found only seven instances in which the dates did not match and most were only one or two days off. OLEPS also examines the differences between dates entered into IA-Pro versus the dates in case files to see if they match. OLEPS, in its most recent audit of OPS, found three instances in which there was a difference between the dates a misconduct case was assigned to an investigator in IA-Pro and the date recorded in the hardcopy case file. OSC’s review concludes that while there is opportunity for improvement, OPS has improved its performance in ensuring the data in IA-Pro matches that reflected in the hardcopy case file.

If a case cannot be completed within 120 days, the investigator must make a request for extension beyond the 120-day requirement. OSC’s case review of 39 files found that of 12 misconduct cases that exceeded the 120-day requirement, three lacked the required request for an extension.

In completing the extension request, an investigator must provide an explanation regarding why the 120-day requirement cannot be met. The explanation contained in the extension request is a valuable tool for OPS in identifying possible systemic issues that may be causing delays in completing investigations. Furthermore, the extension requests hold the investigators accountable for completing their caseload in a timely manner. The request also assists OLEPS and OSC in understanding why delays occurred when conducting their audits and reviews of OPS. Reasons for not meeting the 120-day deadline can include caseload, witness unavailability, and changing investigators. OSC was also told that, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to shift investigators to non-IAIB matters, one investigative unit experienced a backlog of investigations.

The timely resolution of misconduct investigations enables prompt intervention designed to avoid the recurrence of any misconduct and satisfy the public that transgressions by police officers are addressed appropriately. Equally important, troopers who are the subject of misconduct investigations have an interest in the timely resolution of complaints against them. OPS staff noted that trooper promotions or transfers may be delayed until a misconduct investigation has been resolved. Additionally, complainants and the public will have greater confidence in the investigative process if the 120-day rule is adhered to unless extensions are requested. The consistent use of extension requests when appropriate strengthens that public trust by providing a reasonable basis for delays in the investigative process.

OSC recommends that IAIB investigative unit heads ensure IAIB investigators request an extension of the 120-day requirement to complete an investigation when an investigation will exceed such time frame. In its written response to a discussion draft of this report, NJSP agreed with this recommendation and advised that “OPS will continue to work to further improve in this area in accordance with SOP B10 and the Internal Affairs Policy and Procedures Manual (IAPP).”

4. The NJSP Website’s Online Complaint Submission Instructions Require Improvements

NJSP’s website provides information to the public on how to file a complaint against a trooper.[24] OSC has identified two problematic issues with the website instructions that should be improved: the lack of an email address for complaint submissions and the inclusion of a website disclaimer that threatens prosecution and civil action against those who submit frivolous complaints.

a. Email Address for Complaints

Until recently, the only means to file such a complaint was either calling the toll-free Hotline, mailing a letter, or making an in-person complaint. During the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person complaints were no longer being accepted, so the only manner in which complaints could be submitted by the public was via the Hotline or mail. The absence of an email address on the website appears to be a missed opportunity to receive complaints given how much communication is done by email both within and outside of government.

During a February 16, 2021 interview with OPS Intake Unit personnel, OSC learned that an email address did, in fact, exist to which complaints regarding trooper misconduct could be emailed, but that the email address had not yet been made available to the public on the NJSP website.

OSC recommends that NJSP provide an email address for OPS so members of the public can file online complaints, and confirms that OPS has now complied with this recommendation. On February 22, 2021, just over a week after OSC raised the issue with OPS personnel, OSC was informed that NJSP had updated the website to include the email address for filing complaints. OSC was further advised by the Intake and Adjudication Bureau Chief that, as a result of publishing the email address on the website, there has been an increase in complaints. In its response to a discussion draft of this report, NJSP stated that it agreed with OSC’s recommendation and confirmed that after OSC brought this issue to OPS’s attention, the email address was added to NJSP’s website.

b. Website Disclaimer

Although the NJSP website properly provided a description of the complaint submission process and the corrective action that may result from a complaint, it also contained the following caveat in bolded, italicized text: “We take your complaint seriously. However, if a complaint is found to be fabricated and maliciously pursued, the complainant may be subject to criminal prosecution and/or civil proceedings.”[25]

This warning and the threat of prosecution it provides may have had an improper chilling effect on complaints submitted to OPS. And it is unusual to include such a warning in instructions for a law enforcement misconduct tip hotline.[26]

OSC accordingly recommends that NJSP remove disclaimers from its complaint submission instructions that threaten criminal prosecution and/or civil proceedings against complainants. In its written response to the discussion draft of this report, NJSP agreed with OSC’s recommendation and advised that “[a]fter a review of internal affairs best practices, OPS removed the disclaimer from the website effective June 3, 2021.”[27]

B. OSC's Findings Related to the Performance of OLEPS

To examine OLEPS’s performance in its oversight of the disciplinary process, OSC reviewed applicable operating procedures, memoranda, public reports, audits, and supporting audit documentation. OSC interviewed the OLEPS Director and OLEPS staff members. OSC also examined OLEPS’s oversight regarding changes NJSP makes to its rules, regulations, and SOPs pertaining to OPS operations.