The High Price of Unregulated Private Police Training to New Jersey

- Posted on - 12/6/2023

Table of Contents

Introduction

The Office of the State Comptroller (OSC) is authorized to conduct audits, investigations, and reviews of Executive branch entities, including state and local police departments, to identify and prevent fraud, waste, and abuse in the expenditure of public funds. OSC initiated this investigation into Street Cop Training (Street Cop or the Company) after receiving information that public funds were spent to send New Jersey police officers to a six-day conference in October 2021 in Atlantic City that trained officers on questionable policing tactics and contained offensive and discriminatory content (the Conference). Street Cop is a New Jersey-based company.

Around 990 law enforcement officers nationwide attended the Conference, with about 240 from New Jersey. The 240 New Jersey officers came from agencies across the state, working at all levels of government—interstate, state, county, and municipal. The majority of these officers had their attendance paid for by their public employers. OSC’s investigation confirmed that at least $75,000 in public funds were directly spent by New Jersey entities on attendance at the Conference. This number does not include paid time off and/or paid training days relating to officers’ attendance.

To conduct this investigation, OSC’s Police Accountability Project reviewed documents, videos, and other materials received from the Company, training centers, and various law enforcement agencies and departments with officers in attendance at the Conference, among other sources. OSC also consulted directives, regulations, policies, and case law, and conducted interviews of relevant witnesses. OSC also conducted a sworn interview with Street Cop’s founder and Chief Executive Officer, Dennis Benigno.

OSC’s investigation uncovered alarming deficiencies in the police training provided at the Conference and a dangerous and potentially costly gap in the oversight of private post-academy police training. Currently, private post-academy police training in New Jersey is not regulated by the Attorney General, Police Training Commission (PTC), or any other designated entity.

Among other things, OSC found:

- Instructors at the Conference promoted the use of unconstitutional policing tactics for motor vehicle stops;

- Some instructors glorified violence and an excessively militaristic or “warrior” approach to policing. Other presenters spoke disparagingly of the internal affairs process; promoted an “us vs. them” approach; and espoused views and tactics that would undermine almost a decade of police reform efforts in New Jersey, including those aimed at de-escalating civilian-police encounters, building trust with vulnerable populations, and increasing officers’ ability to understand, appreciate, and interact with New Jersey’s diverse population; and

- The Conference included over 100 discriminatory and harassing remarks by speakers and instructors, with repeated references to speakers’ genitalia, lewd gestures, and demeaning quips about women and minorities.

This kind of training comes at too high a price for New Jersey residents. The costs of attendance for training like this is small in comparison to the potential liability for lawsuits involving excessive force, unlawful searches and seizures, and harassment and discrimination. It is well-documented that state and local entities in New Jersey spend millions of dollars litigating these types of allegations. Between 2012 and 2018, over 100 excessive force lawsuits were brought against officers and departments in New Jersey.[1] And in 2022, just one excessive force lawsuit cost a New Jersey county $10 million.[2] The costs of lawsuits alleging discrimination or harassment can be just as expensive. By one estimate, from 2019 to 2023, New Jersey police departments agreed to pay at least $87.8 million to resolve claims of misconduct by officers, and many of those claims involved harassing and discriminatory behaviors.[3] Of course, these quantifiable high dollar amounts do not include the immeasurable and hidden cost to the victims, their families, and their communities.

Quality police training can play a crucial role in ensuring law enforcement is equipped with the knowledge, expertise, and experience to navigate complex and difficult situations safely. But training that encourages officers to employ techniques that violate civil liberties, disparage legitimate public safety initiatives, undermine police reform efforts, and promote a toxic culture in which women and racial and ethnic minorities are made to feel unwelcome — this is not training that should be paid for with New Jersey’s public money.

In light of these findings, and because Street Cop and other private police training companies who receive public funds operate without oversight or regulation by the Attorney General, PTC, or any other designated organization, OSC makes nine recommendations. OSC is also making a number of referrals to appropriate agencies, including to the Attorney General, the Division on Civil Rights, and internal affairs departments for further investigation into OSC’s publicly reported findings, and into additional concerning conduct identified in OSC’s review of the Conference presentations.

**This report and the accompanying videos contain explicit and offensive language and content.**

Background

A. Police Reform Initiatives in New Jersey

Over the past eight years, New Jersey has made significant efforts toward reforming police practices, including prohibiting all forms of racially influenced policing, reevaluating use of force policies, and taking steps to promote positive interactions between police and the communities they serve. Among other reforms, in 2016, the Legislature enacted a law requiring the Department of Law and Public Safety to identify or create a uniform diversity training that would promote positive interactions with all residents within a community, including residents of all racial, ethnic, and religious backgrounds and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals.[4] In turn, the Attorney General issued a directive that established the Community-Law Enforcement Affirmative Relations Continuing Education Institute, also known as the “CLEAR Institute.” Regular training hours of qualifying courses related to these cultural competencies were mandated, including on topics such as “de-escalation techniques; cultural diversity and cultural awareness; racial profiling/racially-influenced policing; implicit bias; conflict resolution; communications skills; crisis intervention training and responding to persons with special needs (e.g., mental health issues); and investigating bias crimes.” Additional training related to appropriate use of force was also endorsed in the directive.

Just three years later, in 2019, the Attorney General’s Office adopted additional comprehensive reforms affecting policing in New Jersey.[5] Coined the “Excellence in Policing Initiative,” the reforms are intended to promote “the culture of professionalism, accountability, and transparency that are the hallmarks of New Jersey’s best law enforcement agencies” and to strengthen trust between law enforcement and the communities they serve. The core of these reforms involved limiting when officers can use force, overhauling police training and culture, ensuring accountability, and building trust with vulnerable populations.[6] The reforms also prioritized de-escalation techniques and training that helps officers identify signs of mental illness so they can more adequately respond to individuals who do not present a threat to others.

In 2020, the PTC voted to create a statewide police licensing program to “overhaul” the statewide training programs for law enforcement officers. Part of this process focused on “modernizing police academy curricula to emphasize a ‘guardian’ mentality rather than a ‘warrior’ mindset” and promoting trust between law enforcement and vulnerable populations including immigrants, LGBTQ individuals, at-risk juveniles, and victims of sexual assault. [7] A related directive noted that it is a “shared responsibility as law enforcement officers to ensure the safety of all of our residents. That is a difficult task that requires, among other things, building trust with marginalized communities so that everyone in New Jersey will feel comfortable approaching law enforcement, whether as a victim, a witness, or a member of the public, including in moments of crisis.”[8]

Also, in December 2020, revisions were made to the “Use of Force Policy” that placed “strict limits” on the use of force and “call[ed] upon law enforcement to protect the life, liberty, and dignity of residents in every interaction.” At the same time, “de-escalation training” was mandated and an online use of force dashboard was launched to provide information to the public about “every use of force incident in New Jersey” to increase accountability.

Additional reforms made by the Attorney General’s Office in this vein included substantial changes to the Internal Affairs Policies and Procedures and the issuance of the Major Discipline Directive, which requires all law enforcement agencies to annually publish names of officers who have been terminated, demoted, or suspended for more than five days due to a disciplinary violation.[9] The ARRIVE (Alternative Response to Reduce Instances of Violence & Escalation) Together mental health-law enforcement co-responder program was also expanded and a working group formed “to study and produce policy recommendations concerning interactions between law enforcement and community-based violence intervention (CBVI) groups.” The efforts to reform policing in New Jersey are ongoing.

B. Regulation of Private Police Training Companies in New Jersey

The PTC, under the authority of the Police Training Act, is responsible for “development and certification of basic training courses for county and local police, sheriffs’ officers, state and county investigators, state and county corrections officers, juvenile detention officers, and a number of other law enforcement positions, as well as several instructor development courses.”[10]

PTC staff are responsible for the “certification of training course curricula, instructors, trainees, and academies authorized to conduct any of the 35 PTC-certified training courses.” PTC staff also “develop operational guidelines to implement applicable training standards, monitor the operation of all PTC certified academies, review all trainee injuries, investigate possible violations of the Police Training Act or PTC Rules occurring during authorized training courses, and handle appeals involving challenges to PTC decisions.”

In addition to those responsibilities, the PTC is now charged with police licensing. In July 2022, two years after the PTC voted to overhaul statewide law enforcement training, the Governor signed legislation that formally created a police licensing system in New Jersey. That law will take effect in January 2024 and will require all law enforcement officers to hold an active license issued by the PTC. In enacting the new law, the Legislature found that “police work . . . is professional in nature, and requires proper educational and clinical training in a State whose population is increasing in relation to its physical area and in a society where greater reliance on better law enforcement through higher standards of efficiency is of paramount need.”[11] The law requires officers to take training courses throughout their career to remain licensed.

However, the new law does not address post-academy training conducted by private police training companies, vendors, and instructors.[12] There are at least 50 police training companies that advertise in-person training in New Jersey, and even more in-state and out-of-state companies that advertise virtual training to New Jersey’s law enforcement community. Because post-academy private police training is unregulated in New Jersey, these companies are operating without any oversight by the PTC or any other designated organization to ensure their training meets even minimal standards and does not contravene current police policy as set by the Attorney General.[13]

C. NJ Criminal Interdiction, LLC d/b/a Street Cop Training

Street Cop, founded in 2012, is a private law enforcement training vendor that conducts business in the State of New Jersey. The founder and CEO of the Company is Dennis Benigno, a former law enforcement officer who worked with a municipal police department in Middlesex County, New Jersey, until 2015.

Benigno claims to lead “one of the largest, if not the largest, police training providers in the United States,” impacting approximately 25,000 to 30,000 law enforcement officers nationally on an annual basis.[14] In New Jersey alone, the Company conducts 40 to 45 courses annually, training in “excess of 2000 state and local law enforcement officers.”[15] Included in the New Jersey course offerings is a case law class “tailored specifically to New Jersey,” which Benigno himself instructs.

Overall, Street Cop offers more than 70 courses taught by over 40 instructors “from a variety of law enforcement agencies nationwide,” including active law enforcement officers with a state agency, county prosecutors' offices, and municipal police departments in New Jersey. Street Cop employs at least seven active New Jersey law enforcement officers. Beyond its for-profit training operation, which is continuously expanding, the Company has a strong free-of-cost online presence, including a private social media law enforcement community that requires verification of employment with over 90,000 followers, an “educational” channel in a popular platform with over 40,000 followers, and a podcast featuring Benigno interviews with Street Cop instructors, among others, about policing issues.

D. The October 2021 Street Cop Conference in Atlantic City, New Jersey

Street Cop hosted a conference at a casino in Atlantic City, New Jersey, between October 3, 2021 and October 8, 2021. The Conference consisted of six days of presentations, which were given by both law enforcement and non-law enforcement speakers and instructors. The format of the presentations was generally lecture-style with some speakers and instructors utilizing videos, images, and PowerPoint slides, while presenting to all of the attendees of the Conference as a group.

Instructors at the Conference included active and former law enforcement officers in New Jersey, as well as active and former law enforcement officers from other states. Presentations were also given by non-law enforcement speakers.[16]

The Company’s records indicate that approximately 240 law enforcement officers from New Jersey attended the Conference.[17] This included officers from one interstate agency, four state agencies, six county agencies, and 77 municipal police departments.[18] The ranks of attending officers from New Jersey varied from patrol to chief/officer-in-charge. Officers attended both in-person and virtually by purchasing the training for on-demand viewing.

Benigno acknowledged in a court filing in a lawsuit against OSC that the Conference was “standard fare” for the Company. He also acknowledged that Street Cop received state and local funds, as well as federal grant money which was made available by local government entities, to send their law enforcement officers to the Company’s training.

OSC has included examples from the presentations in its findings below. Along with this written report, OSC has selected video excerpts from the Conference which further support its findings.[19]

Methodology

Pursuant to N.J.S.A. 52:15B and 52:15C, OSC is responsible for conducting audits, investigations, and reviews of the Executive branch of State government, including entities that exercise Executive branch authority, such as police departments. OSC reports to the Governor, the Legislature, and the public about the extent to which those entities are achieving their goals and objectives, N.J.S.A. 52:15C-5a; if there are areas where cost savings could be achieved; and if misconduct has been detected within the programs and operations of any governmental agency funded by, or disbursing, state funds.[20] Relatedly, OSC is charged with monitoring the procurement processes, N.J.S.A. 52:15C-10, to make sure that taxpayer dollars are protected by ensuring that contracts are competitively bid and are held to high standards of fairness and transparency. And OSC has authority to conduct audits and performance reviews of the New Jersey State Police and the Office of Law Enforcement Professional Standards to “examine stops, post-stop enforcement activities, internal affairs and discipline, decisions not to refer a trooper to internal affairs notwithstanding the existence of a complaint, and training.”[21]

OSC initiated this investigation based on information received that raised concerns about wasteful spending by police departments in New Jersey related to the content of the training at the 2021 Street Cop Conference. To conduct this investigation, OSC examined numerous documents, videos, and other materials received from Street Cop, training centers, and various law enforcement agencies with officers who attended the Conference, among other sources. OSC also reviewed relevant directives, regulations, policies, and case law. OSC reviewed video footage of the Conference provided to OSC by Street Cop. And OSC conducted interviews with active and retired law enforcement officials and individuals involved with police training in New Jersey. In addition, OSC took sworn testimony from Benigno, Street Cop’s founder and CEO.

Multiple lawsuits have delayed OSC’s ability to efficiently obtain the information necessary to complete its investigation. While the New Jersey courts have consistently upheld OSC’s authority to conduct its investigation and obtain the requested information, anticipated additional delays have informed OSC’s decision to issue its findings to date.[22] Based on the available information, OSC determined it is in the public’s interest to have greater transparency now about the lack of oversight of private police training vendors in New Jersey and its attendant risks as set forth in the findings below. However, OSC’s investigation remains ongoing at this time.

OSC sent a discussion draft of this Report to Street Cop to provide the Company with an opportunity to comment on the facts and issues identified. All speakers and instructors referenced in this report also received an opportunity to comment on the portions relevant to their presentations.[23] OSC also provided the Attorney General, PTC, and individual law enforcement agencies with advance notice of OSC’s Report and an opportunity to comment on relevant findings. In preparing this Report, OSC considered the responses received and incorporated them where appropriate.

Findings

A. State and Local Government Entities Wasted Public Funds by Paying for Risky Police Training

Investing in police training is an essential part of maintaining public safety and ensuring an effective, professional, accountable, and well-trained police force. But state and local government investments in training should yield tangible results and foster positive outcomes between the police and the communities they serve. Wasting public funds on training that undermines or even directly contradicts police reform and training initiatives set forth by the State’s chief law enforcement officer squanders public money and compromises reform efforts.

OSC’s investigation demonstrates the actual costs, as well as the risks, of investing in private police training like that provided at the Street Cop Conference. By paying for officers to attend the Conference, state and local government entities implicitly endorsed the training and the conduct promoted at the event. The cost of this poor investment by these entities is not limited to just the amount spent on the training but also includes tangible and intangible costs in the form of potential civil rights violations, excessive uses of force, discrimination, harassment, issues in recruiting women and minorities, significant costs of any resulting litigation, and the erosion of public trust in law enforcement.

OSC’s investigation confirmed that, combined, 54 interstate, state, and local government entities expended over $75,000 to send officers to attend the Conference,[24] not including any paid time off related to attendance.[25] This number is an estimate as OSC was not able to conclusively determine exactly how much was spent by New Jersey public entities on the Conference or exactly who attended or viewed it online because Street Cop produced incomplete and inaccurate information.[26] Street Cop records showed that the Company is an ongoing vendor with New Jersey law enforcement agencies and has received at least $320,000 from various New Jersey agencies for other police trainings conducted between 2019 and 2022, although further investigation showed this number to be drastically underreported.[27]

But as noted above, the immediate financial costs of problematic police training may be a small fraction of the long-term financial costs of such training to the public. As discussed in more detail below, the longer-term financial consequences may include:

- Costs of re-training officers on proper motor vehicle stop procedures and current use of force policies, as well as on discrimination, bias, and harassment laws and policies;

- Costs of litigation and settlement related to officers using unconstitutional policing tactics and excessive force in violation of civilians’ civil rights; and

- Costs of litigation and settlement related to claims of employment discrimination, sexual harassment, and hostile work environment.

And the non-financial costs may also be significant. For nearly a decade, Attorneys General have made significant efforts to reform policing in New Jersey, focusing on de-escalation and decreasing the use of force, approaching policing with a “guardian” mentality rather than a “warrior” mentality, providing accountability through more transparent internal affairs procedures, and highlighting the need for training on cultural awareness, implicit bias, mental health issues, and discrimination. The training at this Conference appears to directly contradict and undermine many of these initiatives.

New Jersey’s state and local governments should not waste public money on training that increases, rather than decreases, the risk of excessive force, unreasonable search and seizure, and discrimination and harassment among members of law enforcement. At least 50 police training companies offer in-person training in New Jersey and even more offer virtual training to New Jersey’s law enforcement community. Yet there are no standards or requirements dictating what can or should be taught to officers at these trainings and no guarantee that what is taught at the courses complies with state or federal law or policies. The findings in the sections below demonstrate the dangers and costs of this “hands-off” approach to private police training.

B. Instructors Taught Unconstitutional Policing Tactics and Techniques

A significant portion of the six-day Conference focused on officers taking proactive steps to detect criminality during the course of motor vehicle stops for speeding and minor traffic violations. OSC found that a number of the tactics taught at the Conference were both unjustifiably harassing and unconstitutional under both New Jersey and federal law.[28]

- Unconstitutional Motor Vehicle Stops – The RAS Checklist

Police are not allowed to randomly stop people for no reason.[29] They are also not allowed to stop a person or a motor vehicle for arbitrary reasons or based on an inarticulate “hunch” or “gut feeling” that the driver or passenger might be engaged in criminal activity.[30] In order for a motor vehicle stop to be lawful, “a police officer must have a reasonable and articulable suspicion that the driver of a vehicle, or its occupants, is committing a motor vehicle violation or a criminal or disorderly persons offense.”[31] Courts look to the “whole picture” to determine whether the facts were sufficient to meet this standard.[32] While the mere fact that conduct could have an innocent explanation does not itself defeat reasonable suspicion, the inferences of criminality drawn by an objectively reasonable officer must be rational and reasonable.[33]

According to multiple speakers at the Conference, one of the main tools that officers should use to assess whether a motorist is engaged in criminal activity—and thus whether to “find a reason” to stop them—is Street Cop’s “Reasonable Suspicion Factors (RAS) Checklist” (RAS Checklist). Trainers suggested that if a driver’s or passenger’s behavior checks enough boxes on the RAS Checklist, those cars should be targeted for stops because the driver or passengers are likely criminals who are trying to avoid detection. Then, after the target motor vehicle is identified and stopped, the RAS Checklist will provide articulable facts that are consistent with criminality that officers could use as justifications to prolong stops, ask for consent to search the vehicle, or call for a canine to sniff the car for drugs. The RAS Checklist was offered to all Conference attendees to assist them in their policing duties going forward.[34]

OSC’s review of the seven-page RAS Checklist revealed that it is largely a compilation of observations an officer might make regarding driving behavior, a driver’s body language before and during a motor vehicle stop, and interviewee responses. The document also describes the conduct that Street Cop believes should be considered suspicious and, in certain instances, explains why it is indicative of criminality. Some of the observations and reasoning find support in case law, but others appear to be arbitrary and contradictory.

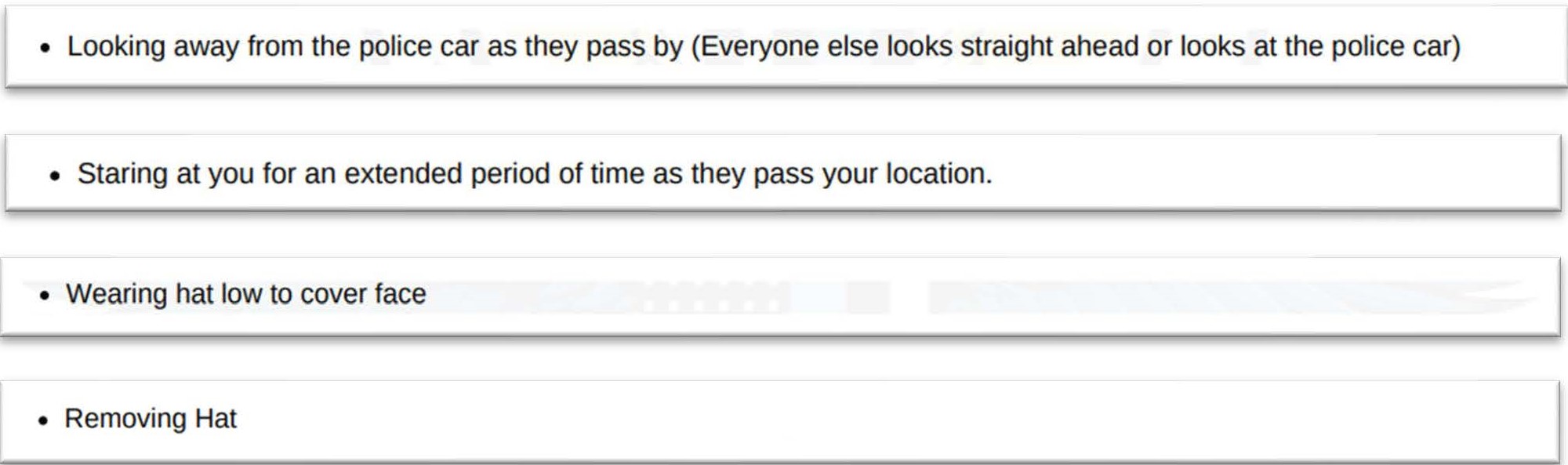

For example, when analyzing driving behavior, the RAS Checklist explains that it is suspicious if the driver passing by a police car looks away from the police car, because “everyone else” will look straight ahead or at the police car. But, according to the checklist, it is also suspicious if the driver looks at the police car to see if the officer is watching them or looks at them for “an extended period of time as they pass [the officer’s] location.” The RAS Checklist explains that it is “not normal” for drivers traveling at or near the speed limit to suddenly brake upon seeing a police car; and it is suspicious if a driver tilts their head, makes some other “slight head movement,” removes their hat, or wears their hat so low that it covers their face. Also listed under suspicious “driving behavior” is “passengers on their cell phone, usually texting,” during a motor vehicle stop, on the theory that a passenger engaged in texting “may be a wanted person.” Excerpts from the RAS Checklist are below.

The list notes that officers should look for motorists turning up their music and singing along, vehicle occupants starting to whisper to one another when they pass the police car, or drivers and passengers “clearly conversing” but looking forward instead of at each other. The checklist does not discuss how an officer would be able to detect whether whispering is occurring while the vehicle is in motion or why it would be troubling for a motorist to look forward at the road while driving rather than at a passenger sitting next to them. According to the checklist, officers should also keep an eye out both for motorists indicating turns “way too soon,” and those “[w]aiting until the very end to turn signal on.”

Many of the “physical factors and behaviors” listed also fail a reasonableness test. The list includes a “Felony Stretch” (which is any stopped motorist stretching their arms, back, or neck in any way while sitting or standing on the side of the road during the pendency of the stop), “not always but often” yawning (regardless of the time of day), and smoking during a motor vehicle stop. During his presentation Benigno, the owner of Street Cop, asserted that smoking during a motor vehicle stop is a “big fucking deal” because, as set forth on the RAS Checklist, there are only three reasons why a motorist would ever smoke a cigarette during a traffic stop: “1. They’re trying to mask an odor”; “2. Trying to calm themselves down”; and “3. It’s their last cigarette before they go to jail.” The checklist warns officers to look out for anyone “Licking Lips to Lubricate Lies,” and those who create “awkward closeness” or “awkward distance” while being interviewed. The checklist highlights that suspicious body language includes “blading” your body so the motorist can see the car and the officer at the same time, but also notes it is suspicious if the motorist stands directly in front of the car or leans on it to “guard it.”

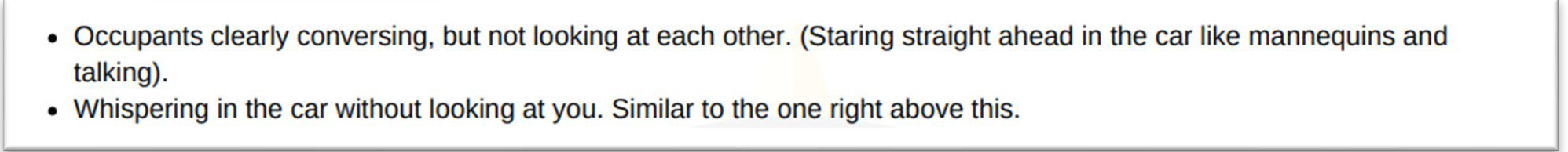

The checklist advises that it is suspicious if the car’s occupants are too nicely dressed if they are traveling a long distance, if they are driving a minivan without a child seat in it, if the car has a “lived-in look” with food wrappers and water bottles, or if the car has a trash bag in it for garbage. It is suspicious if the car has a single key ignition, does not have an EZ Pass, contains more than one cell phone or a backpack, or there is a lawyer’s business card visible inside the car. It is suspicious if a motorist leaves on their turn signal after getting pulled over (referred to as the “Felony Flasher”), and it is also suspicious if the motorist shuts off the car when being asked to step out. If a motorist calls anyone—for example, a family member or friend to tell them they have been pulled over—that too is suspicious. And, among other things, the checklist states that it is suspicious if a “driver becomes very aggressive/agitated” when the officer asks for consent to search their car “after a polite conversation for several minutes.” This suggests that asserting one’s privacy rights is suspicious. The checklist advises that officers should ask everyone they stop for their social security numbers to gauge their response, on the theory that it is an “extremely normal” and common question everywhere in the United States except the “Mid-North and Northwest regions.” And if the motorist questions the reasons for the stop, asks to speak with a supervisor, or says they are either heading to work or heading home, that should all be considered suspicious too.[35]

Because none of these factors are more consistent with guilt than innocence, a stop based on a combination of those factors alone—without some additional factor that suggests criminality—would be unconstitutional.[36] In turn, if any drugs, weapons, or other evidence of criminality was recovered as a result of a stop based on these factors alone, they would likely be suppressed.

Notably, the RAS Checklist contains a disclaimer that it “is in NO WAY meant to be a replacement for formal training, nor is it a comprehensive checklist of every possible factor consistent with criminal activity.” The disclaimer further cautions that “without formal training” an officer “would not be able to properly explain how any of these factors could potentially correlate to criminal activity” and that “[n]one of these factors, by themselves, indicate anything other than the presence of that single factor. . . . In order to establish a nexus with criminal activity, several factors must be observed, and that nexus must be explained through prior training and experience.”

But the training provided at the Street Cop Conference itself failed to establish this nexus. Some of the training included little more than video montages of people stretching and yawning during motor vehicle stops to prove the point that drug traffickers and other criminals stretch and yawn during police encounters. And for many other so-called suspicious factors, the training amounted to little more than an instructor asking rhetorical questions like “why would you say that?” or firmly asserting that a particular behavior, like smoking during a car stop, is significant.

Benigno claimed that employing the techniques from his class and the RAS Checklist would result in the ferreting out of criminality that is missed by officers who do not use his approach. In an effort to prove this point, he showed footage from an uneventful motor vehicle stop that ended with a minor traffic ticket but insisted that application of his methods would have uncovered evidence of serious criminality.

This video clip showed a conversation between an officer and a clearly identifiable woman standing outside of a car the officer had already stopped. The clip does not show the initial stop or whether the officer had already completed a motor vehicle lookup. It also does not provide any context for how long the woman had been stopped at the point when the video clip picks up with the officer asking questions about whether there was anything illegal in her car.

Benigno started and stopped the video clip intermittently to make comments on the woman’s body language and behavior that led him to conclude she is likely “someone who is engaged in some kind of criminal enterprise—whether doing credit card fraud or identity theft or shoplifting, things of that sort.” He also assessed her appearance, which he noted had factored into his conclusion that the woman was “obviously an illicit drug user” because she is “not a runway model, that’s for sure.” Ultimately, the officer never searched the car because the officer’s supervisor arrived on the scene and told him that he was wrong to continue to detain the woman on the side of the road for further investigation.

Nevertheless, Benigno declared that the following factors from his RAS checklist proved that the supervisor was a “fucking idiot” and should have allowed the investigation to continue so a canine unit could have sniffed the car for drugs:

- The woman has her arms crossed like she is “guarding” the vehicle.

- She is smoking a cigarette.

- After being asked if there is a possibility that her passengers have anything illegal in the car, or large sums of currency, she says “not that I know of but I don’t think so because I told them I don’t deal with that shit,” and they are “pretty good guys.”

- She turns her back on the officer for a moment and then leans against the car’s trunk while she keeps talking with the officer.

- When asked whether she has any crack cocaine in the car (after just saying she did not have any drugs in the car), she says “uh” and then chuckles a little before saying “no.”

- When asked if she has “any stolen or fraudulent merchandise in there?” she replies, “No, just all my personal and Paul’s personal.”

- The woman did not consent to allowing the officer to search her car even though they were having a “calm, polite conversation.”

Despite Benigno’s claims to the contrary, the supervisor was correct to direct the officer to release the woman after giving her a traffic ticket. Even giving the officer the benefit of all reasonable inferences from the facts as presented, the combination of these factors alone falls short of the level of suspicion needed to justify the woman’s continued detention to wait for a canine unit to arrive and inspect her vehicle.

The same clip also separately highlights that Benigno suggests to attendees that they should use the fact of a person’s refusal to give consent as further justification for a search or prolonged detention, which is unlawful in New Jersey. In New Jersey, it has been long settled that the police must have reasonable suspicion of criminality before they ask for consent to search a motor vehicle in the first instance.[37] Even outside of New Jersey, many courts have found that a “refusal to consent to a search cannot itself form the basis for reasonable suspicion: ‘it should go without saying that consideration of such a refusal would violate the Fourth Amendment.’”[38] Yet, in addition to the above described clip, there is an entire section of Benigno’s training during the Conference dedicated to an “I Do Not Consent Game,” during which Benigno shows a montage of people refusing consent in an attempt to illustrate that a motorist’s refusal to consent is a suspicious factor that justifies further prolonging an investigative detention.[39] Some images from the presentation are below.

Several other instructors also advocated techniques that could violate constitutional rights.[40] Multiple instructors suggested it was appropriate to stop a motorist solely based on arbitrary factors. For example, instructor Kenny Williams, current Sergeant, Hobart Police Department, stated that, in Indiana, the “speed limit for trucks is 65, [but] for cars it’s 70” and, in his opinion, “there is no fucking way that any car should be behind a semi if you have the ability to pass it.” “When you do that,” Williams explained, “if you are coming through Indiana, I am going to stop your ass . . . all the fucking time” even though you could “be totally legit.” In support of this point, Williams showed video footage where he pulled over a car that was driving behind a truck. It did not appear from the video that the driver committed a motor vehicle infraction or that there were other factors that amounted to reasonable suspicion of criminality that would justify a car stop. A similar situation was illustrated in another video clip, when Williams pulled a car over because it was driving behind a truck, was driving in the lane near but not over the “white fog line,” and it looked like it was a new red car. Williams stated during his presentation that he is “not a fan of red flashy cars.” A slide from Williams’ presentation is below.

Similarly, instructor Tommy Brooks, current law enforcement officer, Boston Police Department, encouraged Conference attendees to stop a designated number of cars to get a “general baseline” of normal behavior during a motor vehicle stop. He instructed officers to choose a day to stop 20 cars on the highway with the “sole purpose” of asking them a series of simple questions such as “where are you coming from” and “where are you going.” Brooks explained that officers should be “real friendly about it” and just see how people answer questions, so they can get a baseline of what is normal and which answers to those same questions “are just weird.” Without an objectively reasonable basis for the stop, those stops, as described, would violate the Fourth Amendment prohibition on unreasonable seizures.[41]

2. Illegally Prolonging Motor Vehicle Stops

During a car stop, police officers are allowed to make “ordinary inquiries” incident to the stop, such as checking the driver’s license, car registration, and insurance, and running a check for outstanding warrants. While making those inquiries, officers are allowed to ask questions of the driver and passenger, even if those questions are unrelated to the justification for pulling over the car in the first instance. But officers are not allowed to perform those inquiries in a way that unreasonably prolongs the stop and can only extend the length of the stop if there is reasonable suspicion of criminality that justifies it. Absent that justification, once the “mission of the stop” is complete, whether it is issuing a ticket or a warning, the police officer must release the motorist to go on their way immediately. If an officer detains a motorist for any additional time—in an effort to develop reasonable suspicion to justify a consent search or request a canine sniff—the stop becomes illegal and any evidence obtained from that point forward (including guns, drugs, and incriminating statements) likely will not be admissible in court.[42] The officer and the police department could also be subject to civil liability.[43]

In addition to training on unconstitutional stops, instructors also provided training that encouraged police officers to illegally prolong stops in violation of the Fourth Amendment. One of the most serious examples of this behavior was illustrated by instructor Brad Gilmore, current Detective, Bergen County Prosecutor’s Office, Narcotics Task Force, when he discussed the way in which instructor Williams appears to prolong car stops by “finger-fucking” his computer and “playing Tetris” while questioning suspects.[44] In other words, Gilmore’s statements endorsed a practice of pretending to conduct a computer lookup so an officer can illegally but surreptitiously continue an investigation during a motor vehicle stop that should have already concluded.

Instructor Williams himself discussed a situation in which he may have unlawfully prolonged a stop. In this stop, Williams had the driver sitting in the front of his patrol car, and Williams can be seen typing on his laptop computer the entire time he has the driver sitting next to him. Williams did not show or describe the entire encounter, and instead used video excerpts to explain when and how he began to suspect the driver had something illegal in his car. Williams noted that seven minutes into the stop, he asked the motorist whether there was anything illegal in the car, at which time the motorist raised for the first time that being in a police car, as a Black man, made him feel nervous. Williams informed the motorist that he was only going to get a “warning for the minor infraction,” and not get a fine or have to go to court. But rather than conclude the stop at this point, Williams continued asking the motorist questions. Williams then explained to the Conference attendees that he ultimately found a large quantity of drugs in this car. However, on the facts shown, there was not a lawful basis for Williams to prolong the stop at that point.[45] These examples used as training material are dangerous, as they create a real risk that Conference attendees will emulate this behavior, civilians’ rights will be violated, and any recovered evidence will likely be suppressed.

Multiple instructors also suggested that if an officer simply assured a motorist that the stop would result in nothing more than a warning or if the officer handed back at least one document to a motorist (such as a driver’s license or an insurance or registration card), it would buy the officer more time to further detain the motorist to confirm or dispel reasonable suspicion with further questioning.[46] For example, instructor Rob Ferreiro, current Lieutenant, Warren Township Police Department (held the rank of sergeant at the time of the Conference), explained his tactic as a “little bit of a mental fuck” where he will return one document to the driver, such as the insurance card, so that they think the stop has concluded and they are free to leave. This approach is legally flawed. If a reasonable person would not feel free to leave—and “[a]s a practical matter, citizens almost never feel free to end an encounter initiated by the police”—providing an assurance or giving some but not all documents back to the motorist will not legitimatize a stop that has been illegally prolonged.[47]

When OSC asked during an interview whether the presentations given are reviewed for compliance with the law, Benigno did not respond to the question directly but rather stated that “nothing [was] brought to my attention that was in non-compliance with the law.” He further explained that “our instructors aren’t teaching case law unless they’re a case law instructor.”[48] As evidenced by the above examples, this approach to police training is as flawed as it is dangerous.

C. Street Cop Training Undermined NJ’s Police Reform Initiatives

Despite the many reforms in place in New Jersey at the time of the Conference[49] and the nation-wide shift towards community or problem-oriented policing, OSC found that presenters at the Conference made comments that directly contradicted those reforms in several ways, including promoting a militaristic style of policing, undermining state-mandated training and safety initiatives, encouraging insubordination, and dehumanizing civilians.[50] Some examples are below.

- Promoting a Militaristic Approach to Policing

Speakers throughout the Conference made comments glorifying violence and the application of military techniques to policing. These instructors encouraged officers to adopt a warrior/enemy mentality, rather than the “guardian” approach that is more consistent with police reform initiatives.

For example, non-law enforcement speaker Tim Kennedy made comments about “loving violence” and later displayed a slide advising attendees to “Be the calmest person in the room but have a plan to kill everyone.” He praised savagery and “drinking out of the skulls of our enemies,” which he described as “fucking rad, right?” Instructor Sean Barnette, then SWAT Medic and Deputy Sheriff for the Oklahoma County Sheriff’s Office, joked about law enforcement officers loving guns and “shooting folks . . . not shooting folks, but shooting well. Sometimes you have to shoot folks.” Former New York Police Department Detective Ralph Friedman stated that he felt “victorious” about having killed people in the line of duty and described his involvement in 13 incidents of deadly force, when he shot eight people, killing four, as “batting .500.” Instructor Shawn Pardazi, a former law enforcement officer, mimicked the sound of gunshots to describe how he would pursue a suspect.[51]

Benigno also made several comments that encouraged officers to adopt the warrior/enemy mentality. During his presentation, Benigno asked attendees why they are “treating this job like it won’t take your fucking life in a second,” questioned whether they want to be at holidays or their next birthdays, and advised attending officers to “treat every motor vehicle stop as if you are going to die and you might just live.” Comments such as this are reflective of a hyper-vigilant “warrior” mentality to policing, in which every interaction with a civilian is to be treated as a potential deadly threat. Benigno also used a clip from a television show about policing during his presentation, which he described as a life-threatening situation that should have been handled in a completely different manner. Contrary to Benigno’s assertions, the suspect in the video readily submits to the officer’s authority and is arrested without incident or any use of force.

A major theme with many speakers at the Conference was an “us versus them” mentality—law enforcement officers versus civilians, liberals versus conservatives, or those officers who follow Street Cop’s teachings versus those who do not. Instructor Tom Rizzo, current Captain, Howell Township Police Department, even referred to Street Cop as “starting a god damn army.”[52] Instructor Kivet, current Sergeant, Robbinsville Township Police Department, called the Street Cop logo a “family crest” and Benigno stated during his presentation that if an officer is at the Conference they know the officer is “on our side.”[53] Some images used during Rizzo’s presentation are below.

Millions of dollars are spent on litigating allegations of excessive force brought against officers and law enforcement agencies in New Jersey. There were over 100 excessive force lawsuits brought against officers and departments in New Jersey between 2012 and 2018. And last year, just one excessive force-related settlement cost a county in New Jersey $10 million. There is also a substantial non-monetary impact of these incidents on victims, as well as their families and communities. In addition, these tragic incidents contribute to the erosion of trust between law enforcement and the communities they serve. Training that promotes militarization, rather than focusing on de-escalation and limiting the use of force, does not support the goals of the Excellence in Policing Initiative and increases the likelihood that officers will employ tactics that could result in harm to civilians, other officers, and law enforcement agencies/departments.[54]

2. Undermining State-Mandated Training & Safety Initiatives

Several instructors at the Conference mocked, undermined, and disparaged police reform initiatives, mandated police academy training, and public safety initiatives focusing on drunk driving or speeding.

For example, during his presentation, Benigno criticized police academy training, repeatedly asserting that academies do not actually teach officers how to do their jobs. He warned attendees that “police academies, not intentionally, are killing cops. They are fucking killing cops.” To further this point, Benigno told the attendees to watch videos of officers being killed in the line of duty and stated that “90 percent” of those officers were “failed by their academy, their field training, their administrations, the world, and/or themselves.”

Instructor Rizzo appeared to mock the “Excellence in Policing, Policing Reimagined” Initiative, when he discussed policing being “reimagined” in his presentation (see slide from his presentation above). In doing so, he also appeared to mock the LGBTQ community, instructing officers to tell “he or she, him, her, she, him, whatever the fuck you want to call people now” that the police have “reimagined the hell” out of themselves.

Multiple presentations endorsed the idea that a police officer’s sole focus should be criminal “interdiction,” and that other kinds of police work and public safety initiatives are less important.[55] Several instructors made disparaging comments about “sensitivity training” or implied that officers should not have to “accommodate” or be “sensitive to everybody and their condition” or to every “color of rainbow.”

Insisting that officers should be focused solely on identifying criminals, Benigno mocked officers who “hammer[] out fucking tickets like they are going out of style.” He told attendees that police officers do not conduct motor vehicle stops for speeding because they “care about your loved ones” and are trying to save lives. Instead, Benigno noted that Conference attendees would likely stop a fellow officer doing “106 in a 50” and let them go without any enforcement.[56] Instructor Kivet made a similarly disparaging reference, joking about officers in his own department being “ticket Nazis” with the “moustache and everything, man.”[57]

Along the same lines, multiple presenters appeared to suggest that stopping vehicles for drunk driving is less important than “knocking down warrants” or discovering a large stash of narcotics. For example, Benigno expressed annoyance about stopping motorists who are driving under the influence, mimicking their slurred speech and explaining he does not want people “shitting in his back seat.” Kivet also appeared to discount the importance of stopping intoxicated motorists, noting that he used “to be big with that before I really got into narcotics.” According to Kivet, if an officer wants to be respected or have their department respected, they should work hard to shift their efforts away from accidents and traffic violations and focus instead on proactive policing that will result in finding large quantities of drugs in cars.

3. Encouraging Insubordination

Insubordination—commonly defined as the failure to obey a lawful order—has serious implications for policing in New Jersey and can result in major discipline being imposed on an officer, as evidenced from the incidents of insubordination recorded in the Major Discipline Reports from 2020 to 2022.[58] Yet several of the instructors referenced and justified insubordinate behaviors. This included comments that glorified ignoring the direct orders of higher ranking officers, failing to follow the legal advice of prosecutors, and even undermining the decision making authority of the courts. At best, insubordination undermines the proper and efficient functioning of the law enforcement agency. At worst, it can compromise officer safety, the safety of others, and the integrity of the criminal justice system as a whole.

During his presentation, instructor Gilmore shared an anecdote from his career when an officer observed what Gilmore believed to be a hidden compartment under a parked vehicle. Even though the officer’s sergeant apparently instructed him not to proceed with investigating the vehicle, Gilmore, who was not in the officer’s direct chain of command, encouraged the officer to disregard that order and to continue with the investigation, which was eventually taken over by Gilmore’s department. The outcome in that case was touted by Gilmore as being positive because criminal activity was uncovered. But Gilmore did not disclose the outcome for the insubordinate officer during his presentation or discuss the safety issues and other implications of continuing with the investigation without the support of the officer’s department.

Street Cop’s training did not just suggest that officers ignore direct orders. Benigno also attacked police administrations during his presentation, making comments like: “bad [police] administrations are a criminal’s best friend.” During his presentation titled “Constitutional Policing,” instructor Zach Miller stated that there is “misinformation floating around” among departments, prosecutors’ offices, and even judges about what the law is and what officers can and cannot do based on “misunderstandings” of the applicable law. He seemed to suggest that his interpretation of case law is superior to others, and if officers just listen to him, or read case law like he does, they can disregard the opinion of those “misinformed” departments, prosecutors, or judges about what is lawful and how to conduct themselves during investigations.[59]

There were also comments made during the Conference that downplayed the significance of the internal affairs function and discipline imposed for officer misconduct in general. For example, Gilmore made comments about how officers get “kicked in the dick one too many times” or “get in trouble by [internal affairs]” and how that causes them to “lose their motivation.” He also referenced “how many times [he] was kicked in the dick” or “yelled at” but continued with the same conduct. Similarly, during his presentation on Day 2 of the Conference, Benigno made the comment, “You’re the police. You’re supposed to find trouble,” but then clarified that he was not referring to trouble like doing “something stupid and getting your pee-pee slapped around,” which mocked being disciplined for misconduct. These statements are not only inappropriate, but suggest that an officer’s response to receiving a direct order from a higher ranking officer or having an internal affairs complaint made against the officer should generally be to disregard it.

4. Dehumanizing Civilians

Other comments made by instructors at the Conference that undermined the New Jersey police reform initiatives were those that dehumanized civilians or indicated to the attendees that officers or their friends/families would be treated differently than other civilians.

For example, while discussing the correct application of a tourniquet during his presentation, instructor Barnette compared providing medical treatment to suspects, referred to as “gang bangers” and the “pieces of shit of society,” to treating law enforcement officers. He stated that “we don’t like to treat the turds” but these people can be thought of as “live tissue labs” that provide practice or “reps” for when someone needs to provide treatment to a fellow officer who was injured in the line of duty. During these remarks, Barnette acknowledged that this was not a politically correct or “PC” thing to say.

Benigno also asked the attendees “who in this room is addicted to the game,” to “catching mother fuckers” and “bad guys.” Another comment made by Benigno both dehumanized civilians and appeared to contradict the Attorney General’s Use of Force Policy.[60] In discussing the reasons why a civilian would hold their cell phone during a motor vehicle stop, Benigno mocked the “guy who is fucking recording you” and stated that that person was about to “get pepper sprayed, fucking tased, windows broken out, motherfucker.” Based on the scenario posed by Benigno, there appeared to be no justifiable reason to use force against the hypothetical civilian who was simply recording an interaction with law enforcement officers on a cell phone.[61]

Instructor Rizzo described a scenario in which officers were filmed or photographed shaving people experiencing homelessness. Rizzo stated that, while this was presented as “great PR” and “community outreach,” in reality these pictures were taken to “bust balls” of other officers. This comment mocked community outreach that would improve the relationship between law enforcement and the communities they serve and appeared to counter the larger message of the presentation, officer resiliency.

Multiple presenters also used videos and memes to suggest civilians were stupid and, in some cases, akin to animals. For example, instructor Kivet showed an offensive meme of a monkey in a shirt after describing a motor vehicle stop of a “75 year old Black man coming out of Trenton.” The image from Kivet’s presentation is below.

To achieve change, the law enforcement community must overcome “resistance from the subculture of the police, a subculture that is focused on danger, authority, and efficiency,” a culture of policing that has “successfully resisted, and in fact defeated, change attempts.”[62] Unfortunately, these comments made throughout the Conference were not reflective of a shift towards community or problem-oriented policing, as envisioned by the Excellence in Policing Initiative, but rather supported an approach in which the ends justified the means used to identify and pursue criminal suspects.

D. Instructors Made Over 100 Discriminatory and/or Harassing Comments

Conference attendees were inundated with discriminatory and harassing comments, lewd gestures, and offensive and crude remarks that touched on characteristics that are protected under the New Jersey Law Against Discrimination (NJLAD) and/or applicable anti-discrimination and harassment policies.

1. New Jersey Law Against Discrimination

The NJLAD prohibits discrimination and harassment based on actual or perceived race, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, and other protected characteristics in employment, housing, and places of public accommodation.[63] The NJLAD also prohibits police officers and agencies from harassing members of the public, regardless of their being in police custody or not, on the basis of any protected characteristic. According to the New Jersey Attorney General’s Office, “[d]epending on the circumstances, even use of a single slur by an officer in a police encounter may violate the [NJLAD].”[64] Moreover, the law is clear that, regardless of whether the discrimination, harassment, or hostile work environment created was intentional, the NJLAD applies because “it is at the effects of discrimination that the [NJLAD] is aimed.”[65] That is, even so-called “jokes” which lead to subjective feelings of humiliation can be found to violate the NJLAD.[66]

OSC asked whether Street Cop believed the NJLAD applied to its training events. In response, Benigno acknowledged that the Company “understand[s] the basics of the laws against discrimination” and does their “very best to ensure” that they “are conforming with those guidelines of those laws.”

2. New Jersey Policy Prohibiting Discrimination in the Workplace (the Policy)

The New Jersey Policy Prohibiting Discrimination in the Workplace (the Policy) is a “zero tolerance” policy that prohibits employment discrimination and harassment based on race, creed, color, national origin, nationality, ancestry, age, sex/gender, pregnancy, marital status, civil union status, domestic partnership status, familial status, religion, affectional or sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, atypical hereditary cellular or blood trait, genetic information, liability for service in the Armed Forces of the United States, or disability. The Policy also plainly states that it applies to “persons doing business with the State,” which includes vendors like Street Cop that accept state funds. In relation to the Conference, Street Cop accepted funds from multiple state agencies to train state law enforcement officers on how to perform their official function. The Policy applies not only to the workplace but also to “conduct that occurs at any location that can be reasonably regarded as an extension of the workplace,” and to “third party harassment,” which is unwelcome behavior involving any of the protected categories . . . that is not directed at an individual but exists in the workplace and interferes with an individual’s ability to do his/her or their job.” All employees are encouraged to promptly report violations of the Policy, but reporting violations is mandatory for all supervisors.

OSC asked Benigno whether he was aware of this Policy. In response, Benigno said he was aware the Policy exists, but could not recall reviewing it, and was unsure if the fact that state employees attended the Conference meant that it applied at the Conference.

3. Other Applicable Anti-Discrimination and Harassment Policies

OSC also obtained copies of workplace harassment policies, directives, rules, and regulations (collectively “the policies”) from the employers of the various New Jersey law enforcement attendees of the Conference. Based on a review of these documents, OSC found that most, if not all of the policies were implicated in some way by many of the speakers at the Conference. When OSC asked Benigno whether he was aware if local department anti-harassment and discrimination policies would apply to officers attending the Conference, Benigno said he was “unfamiliar” with that.

The policies reviewed were variations on a common theme—that discrimination and harassment are prohibited in the workplace and that employees often have a duty to prevent and stop such behaviors, including by reporting such conduct when it occurs. Some policies explicitly prohibited officers from using unwanted nicknames, and making insensitive comments, off-color jokes, and “so-called innocent remarks.” Some policies also explicitly prohibited officers from using sexual innuendo, and discussing “sexual prowess or sexual deficiencies.” Like the State Policy, many of the department policies similarly placed additional responsibilities on supervisors and made clear they apply to any location that could be considered an extension of the workplace. Below are some prohibited activities described in selected excerpts of anti-discrimination and harassment policies from departments that had officers in attendance at the Conference.

4. New Jersey State Police Policies

The State Policy described above applies to the New Jersey State Police (NJSP), which had multiple troopers in attendance at the Conference. In addition, NJSP has its own policies that address the need to report problematic training. It also has a unique reporting requirement imposed by state law that mandates any member of New Jersey State Police who attends a training course or program to “report to the superintendent, through the chain of the command, if the member knows or reasonably should know that the instruction provided during the course contradicts any Division of State Police rule, regulation, standing operating procedure, or operations instruction relating to any applicable non-discrimination policy established by the Attorney General; the law of arrest, search, seizure or equal protection; or the manner for lawfully conducting motor vehicle stops or post-stop enforcement actions.”[67]

Even though violations of these anti-discrimination and harassment policies at the Conference were rampant, as discussed below under Section E, OSC’s investigation did not identify a single report from the period before its investigation began by a New Jersey officer or trooper in attendance regarding any concerns or negative feedback about the 2021 Conference.[68]

5. Costs Associated with Violations of the NJLAD and State and Local Policies

In New Jersey, millions of dollars are spent by the State, counties, and municipalities on litigating cases brought against law enforcement agencies and officers under the NJLAD. Since 2019, New Jersey police departments “have agreed to pay at least $87.8 million to resolve claims of misconduct by its officers,” and many of those claims involved harassing and discriminatory behaviors.[69]

Discrimination, harassment, and hostile work environment cases brought by officers in New Jersey against their employing departments alone have resulted in multiple settlements costing $1 million or more. A sample of just 12 of those cases resolved between 2018 and 2023, some with multiple victims, totaled almost $22 million in payouts. This is only a fraction of the public funds spent on the litigation and settlement of the NJLAD cases within New Jersey law enforcement agencies, and it does not include any complaints made by civilians.[70]

The non-monetary effects of harassment and discrimination on the police force are equally, if not more, costly. Major discipline has been imposed on law enforcement officers for behaviors on and off duty that were discriminatory or harassing. As recorded in the Major Discipline Reports from 2020 to 2022, in just three years, there were administrative charges brought for at least 20 incidents described as “discrimination,” “violates Policy Prohibiting Discrimination in the Workplace,” “harassment,” “harassment in workplace,” “discrimination that affects Equal Employment Opportunity (‘EEO’) including sexual harassment,” “cyber-harassment,” and incidents involving “inappropriate relationships.” Discipline imposed in these instances ranged from suspensions to termination from employment, and even issuance of summonses and criminal charges.

New Jersey law enforcement agencies also face great difficulty in hiring a diverse workforce. Although the New Jersey Attorney General and police agencies acknowledge the need to diversify the police force, 2022 data shows that 72 New Jersey police departments were staffed by only White officers, while 108 departments were staffed by only men. Women apply to the job at much lower rates than men and that number decreases throughout the application, graduation, and promotion process. Meanwhile, racial and ethnic minorities combined apply at higher rates but are hired and promoted at a disproportionately lower rate.[71] It has been recognized that “[i]n a state as diverse as New Jersey, it is imperative that law enforcement reflect the diversity of the communities we serve, especially as we seek to build trust between police and the community members they are sworn to protect.” Training that normalizes harassment and discrimination has the potential to seriously undermine the ongoing attempt to recruit, hire, and retain a diverse police force.

Despite the extensive monetary and non-monetary costs and consequences of harassment and discrimination to agencies/departments, officers, and communities, OSC found that throughout the Conference, speakers made over 100 comments that touched on one or more of the protected characteristics under the NJLAD or otherwise violated the plain language of applicable anti-discrimination and harassment policies.

A sampling of the over 100 comments made at the Conference are described below.[72] The prevalence of these discriminatory comments completely overshadowed those aspects of the Conference that otherwise provided appropriate police training.

a. Protected Category – Gender/Sex

As discussed above, while the law and applicable policies prohibit discrimination and harassment on the basis of gender/sex, OSC found extensive comments made by speakers and instructors at the Conference that implicated this protected category.

On Day 2 of the Conference, in a presentation titled “15 Tactics for Greater Success,” instructor Benigno made several comments touching on the protected category of gender/sex. Benigno glorified being surrounded by “hookers and cocaine,” made light of police leadership pursuing sexual relationships with young police dispatchers, asked if it would be weird to perform a sex act on an officer that endorsed his training, and talked about the size of his penis (a comment later referenced by other speakers). Benigno also described a suspect as not a “runway model” and told someone who criticized his training not to be a “fucking bitch.” Benigno also started his presentation with a song that included the word “bitch” which could be heard multiple times as Benigno approached the stage.

On Day 3 of the Conference, during the presentation about “Tradecraft and Criminal Behavior,” instructor Pardazi compared approaching criminal suspects to approaching people at a nightclub. In the course of this comparison, Pardazi utilized several sexually suggestive, gender/sex-based slang terms including “booty-booty,” “punanny,” and “poontang,” and stated that someone should act like a “fucking gigolo” and not sound like “casting couch” when they make their approach. He stated that “This ain’t tinder. You ain’t just swiping right and left.” He continued the nightclub analogy later in the presentation and stated that while someone might still be evaluating how to make their approach, someone else has already left the club to take an “Uber somewhere.” Pardazi prefaced his comments with the statement that he has “no fucking filter.”[73]

Several instructors used images or videos along with their unacceptable gender/sex-based comments. During another presentation on Day 3 titled “Criminal Vehicles and Occupants,” instructor Ferreiro used a video clip from a women’s mixed martial arts (MMA) fight to demonstrate a point about making eye contact with drivers during motor vehicle stops—a tactic that he repeatedly referred to as “eye fucking.” Prior to playing the video, Ferreiro stated “no disrespect to any females in this room” and after it concluded, Ferreiro described the video as a male “catching himself looking” at the female MMA fighter. He stated that the male’s eyes trigger a physical response in his body and that the male was “adjusting himself,” as Ferreiro then demonstrated. Later in the presentation, Ferreiro described an interaction he had with a suspect during a motor vehicle stop and stated that he “eye fucked the shit out of the female driver. She doesn’t want to fuck me back though.”

Similarly, on Day 4, during a presentation titled “The Gun Game,” instructor Brooks described a behavior he had observed with criminal suspects that he called the “sneaky peek.” To illustrate this behavior, Brooks used a video clip of a person dressed in form-fitting pants and a cropped shirt while reaching for an item on a shelf. While the video played on a loop, Brooks demonstrated taking a “sneaky peak” at the person’s body while faking a phone call.[74]

During the presentation titled “Drug Identification,” held on Day 5, instructor Kivet used images of the Street Cop Training company employees. In thanking the staff members, he called these women “the real housewives of Street Cop Training.” Then in referring to the male instructors at Street Cop Training, he stated “You are not as pretty as these girls. Some of them are single. Buy them a drink tonight.” Later in his presentation, Kivet displayed a video depicting women dancing on top of a police vehicle in Chicago. His usage of this video clip appeared to be entirely gratuitous.

During a presentation on Day 5 of the Conference titled “Social Media Investigations,” instructor Nick Jerman, current law enforcement officer, Montgomery County Police Department, utilized several images of women in lingerie apparently from social media, one of which he referred to as a “human trafficking victim.” The use of these images did not further his presentation in any relevant way. Jerman also suggested that attendees use the investigative techniques learned in his class to their advantage in their “personal lives” and discussed uncovering information online about a woman before approaching her at a wedding. He also utilized an image during his presentation that said “work stuff, not porn.”

OSC found that instructors engaged attendees of the Conference in their harassing behaviors at times as well. During his presentation on Day 2 of the Conference titled “The Sheepdog,” speaker Kennedy pointed at audience members and asked if they would “whip” him. Kennedy also referred to “buying a bitch” during a counter human trafficking operation and having a “soiree in a hotel room” with multiple women after an MMA fight. He also repeatedly referred to women in derogatory and demeaning terms.

At the beginning of his presentation on Day 3 of the Conference titled “Life or Death Medical Knowledge for Police,” Barnette stated that the presentation was “rated mature” because he likes to “say fuck a lot” and that any sexual content in the presentation does not include pictures of himself. Later in his presentation, Barnette compared the use of the medical techniques he was teaching to having sex for the first time. He then pointed to an audience member and indicated that the audience member “would not know what that feels like.” Instructor Barnette later used a volunteer from the audience for a demonstration of how to rake a person’s body for bullet entrance wounds. After he released the volunteer back to his seat, Barnette stated that the volunteer had “nice pecs by the way, just saying for the ladies.” At the end of this presentation, Benigno can be heard telling the audience that Barnette would be at the hotel spa later to answer questions “with nothing on.”

During his presentation on Day 2 of the Conference, Gilmore stated that officers should be suspicious if a suspect uses a women (mother, grandmother, etc.) as an excuse in an interview during a motor vehicle stop because women are associated with “innocence.” On the other hand, Kivet referred to a man owning a candle as a reasonable basis to believe that the item was associated drug paraphernalia because “why would a man have a small candle.”

The prevalence of these gender/sex-based comments, references, and images/videos throughout the entire Conference flouted applicable laws intended to eradicate the “cancer of discrimination” in New Jersey and showed blatant disregard for anti-discrimination and harassment policies.[75] These remarks increase, rather than decrease, the risk that New Jersey law enforcement officers and agencies will face civil liability for allegations of sexual harassment, hostile work environment, and discrimination. Additional lewd and inappropriate comments, some of which also touched on the protected category of gender/sex, are discussed below under subsection d.

b. Protected Categories – Color, Race, Ethnicity, and/or National Origin

OSC also found that many comments were made during the Conference that touched on the protected categories of color, race, ethnicity, and/or national origin. During the block on “Tradecraft and Criminal Behavior” on Day 4 of the Conference, instructor Pardazi used a variety of accents, indicating that he “play[s] Mexican when I walk into the gas station” by using names like “Juan one day, Jose, Mario” and stated that depending on “what part of the south” he was in, he might “be Italian.” He then stated that he had multiple personality disorder. Pardazi also made a number of comments about people of Middle Eastern descent, including stating that he himself is from the Middle East where “everything is a business,” including marriage arrangements, and for “150K you can have her all day long.”[76] He then remarked that the “Middle Eastern folks in the class are like dude shut up.” Pardazi also indicated that he works in counter-terrorism because “takes one to know one” and referred to the Taliban as “bringing my cousins into it.” Pardazi also made a comment about human bodies versus car bodies and stated “whoa he went there” and it was “Middle Eastern shit.” He also indicated surprise during an interaction with a suspect and stated, “I am the Middle Eastern guy and mother fucker trying to sell me some shit.”

During the block on “Mastering Interdiction” on Day 3 of the Conference, instructor Williams used a video of a motor vehicle stop in which he was questioning an Asian male suspect. He stated that “you can even teach guys that don’t speak that good English” to handcuff themselves (a technique he was seen using in several of the videos during the Conference). He also used a clip from an action/comedy movie about police officers where a Black actor speaks in a derogatory manner to an Asian actor. His presentation also started with a song that included the N-word, which was heard as Williams approached the stage.

Other comments touching on these protected categories included: Instructor Morgan referred to the “hood and the woods” in describing the county he works in New Jersey (identified as Camden County from images used during the presentation) and utilized images of a drug addict, as well as a clip from a movie which reinforced stereotypes. Instructor Rizzo played a video of a newscaster mistakenly using racially offensive names during a report about a plane crash and he added another racially offensive name after the clip was played.

c. Other Protected Categories – Sexual Orientation/Gender Identity or Expression, Religion or Creed, and Disability

OSC found that instructors and speakers at the Conference made numerous comments and references that touched on other protected categories. Some examples are below.

As discussed above, Rizzo stated during his presentation titled “Lead Me” on Day 3 of the Conference that if the audience members are questioned by someone about whether the police have “reimagined” themselves, they should tell “he or she, him, her, she, him, whatever the fuck you want to call people now” that they have “reimagined the hell” out of themselves. Another speaker indicated that it was burdensome for officers to be sensitive to the needs of the LGBTQ community and to understand “every color of the rainbow.”

In addition, during his presentation titled “Flipping Informants” on Day 3 of the Conference, Morgan utilized a picture of a transgender celebrity when describing how confidential informants would only be referred to as “he/she or they” in a report, as not to reveal an informant’s identity. The use of the image was demeaning to transgender and non-binary people. During his presentation, Benigno mocked officers, who he said drink a “gay ass” brand of alcoholic beverages on the weekends with only male friends and “not one girl.”