The Department of Corrections’ Internal Affairs Unit Failed to Adequately Investigate Abuse Allegations

- Posted on - 06/6/2024

Table of Contents

Introduction

The Office of the State Comptroller (OSC) initiated an investigation into the processes and practices of the Special Investigations Division (SID), the internal affairs unit within the Department of Corrections (DOC), upon receipt of complaints alleging that SID’s investigations and record-keeping practices were inadequate. SID is responsible for investigating and uncovering, among other things, allegations of correctional police officer misconduct. In that capacity, SID is intended to function as a vital tool in exposing and preventing such abuses.

OSC’s investigation revealed deficiencies in the thoroughness and objectivity of SID’s investigations. OSC identified two incidents in which correctional police officers at Bayside State Prison appear to have used excessive force against incarcerated people. In one, an incident from 2019, an incarcerated person was struck in the face multiple times and wrestled to the ground, but surveillance video showed no visible provocation or threat against the officer. In the second, an incident from 2018, an incarcerated person was pepper-sprayed and wrestled to the ground, again with no visible provocation or threat against the officer. In each instance, the assigned SID investigators failed to interview key eyewitnesses, raising concerns that the investigations were inadequate and casting doubt on their integrity and effectiveness in cases that clearly called for extensive scrutiny and fact gathering. As a result of these deficiencies, DOC did not identify likely cases of excessive force, and the officers involved received no discipline.

SID’s failure to conduct comprehensive investigations was not limited to these two incidents. For this investigation, OSC examined a sample of 46 case files from internal investigations involving allegations of assault, excessive force, and violations of the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) by DOC staff against incarcerated people at three state prisons from January 2018 to August 2022. In 22 percent of the cases reviewed, SID investigators did not conduct the most basic investigatory step of interviewing all eyewitnesses. In addition, in most cases, SID did not recommend dispositions or clearly articulate whether an allegation was substantiated by the evidence. Further, key evidence was missing from nearly 13 percent of the investigative files reviewed. Several factors contributed to these deficiencies, including a code of silence in law enforcement, a lack of clear policies and procedures, and inadequate training.

These findings follow multiple reports documenting abuses by DOC staff members against incarcerated people. In 2020, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) found that DOC failed to keep incarcerated people at the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women (Edna Mahan) safe from sexual abuse by staff. DOJ also found that SID failed to conduct adequate investigations into allegations of sexual abuse at the facility. Similarly, correctional police officers and supervisors at Edna Mahan were criminally indicted after officers at the facility were accused of assaulting several inmates in January 2021.

Likewise, in May 2023, a DOC correctional police officer at Bayside State Prison was sentenced to 30 months in prison for conspiring with others to physically assault inmates in what was deemed a kitchen “fight club.” More recently, in February 2024, a former correctional police officer at Bayside State Prison pled guilty to violating the civil rights of incarcerated people in his custody after he failed to intervene in or report multiple assaults of incarcerated people.

The public has a vital interest in ensuring that all internal investigations into allegations of correctional police officer misconduct against incarcerated people are thorough, objective, and impartial in ensuring that appropriate discipline is imposed. The State also has a legal duty to ensure incarcerated people are safe and their rights are protected while they serve their sentences. Internal affairs investigations are effectively a form of self-policing—and to be effective, they must follow strict protocols. Without a robust internal affairs process that ensures correctional police officer misconduct is not covered up, the deficiencies identified by OSC will persist, resulting in a lack of officer accountability, more abuse of inmates, and further damage to public trust.

During the course of this investigation, DOC restructured SID’s management and instituted a number of reform measures to address some of the deficiencies identified by this investigation. Those measures represent positive initial steps, but additional action is required. To that end, OSC makes eleven recommendations for DOC to address the findings contained in this report, and has referred these findings to the Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson (OCO), an office tasked with providing independent prison oversight to protect the safety, health, and well-being of incarcerated people.[1]

Background

A. New Jersey Department of Corrections

The mission of DOC is to “advanc[e] public safety and promot[e] successful reintegration in a dignified, safe, secure, rehabilitative, and gender-informed environment, supported by a professional, trained, and diverse workforce, enhanced by community engagement.” DOC seeks to accomplish this mission through effective supervision, classification, and appropriate treatment of incarcerated people. DOC consists of multiple program areas and divisions, including the Division of Operations, which operates its correctional facilities. DOC operates nine correctional facilities across the state, housing approximately 13,600 incarcerated people in minimum, medium, and maximum-security level facilities.

Among its other functions, the Division of Operations is responsible for maintaining security at all the state’s correctional facilities. To support this security function, the Division of Operations employs approximately five thousand uniformed correctional police officers. Correctional police officers are responsible for the day-to-day operations of the DOC facilities to which they are assigned and report to the facility’s administrator. A facility’s administrator is responsible for all facets of a correctional facility’s operations, including issuing discipline to custody staff when warranted.

Both correctional police officers and SID investigators are sworn law enforcement officers. These officers are empowered to exercise full police powers and to act as peace officers at all times for the detection, apprehension, arrest, and conviction of criminal offenders.[2]DOC is the largest employer of police officers in the State.[3]

B. The Special Investigations Division within the Department of Corrections

SID functions as DOC’s internal affairs unit and is responsible for investigating alleged improper or illegal behavior committed by any DOC employee, incarcerated person, or other individual involved with a DOC facility. SID’s internal affairs function includes investigating allegations of officer misconduct, such as the use of excessive force.

SID consists of sixteen units performing a variety of law enforcement functions. Eleven units are responsible for conducting internal affairs investigations, including a field unit at each of DOC’s nine primary prisons. Two additional investigative units are the Professional Services Unit and the Special Victims Unit[4] (SVU). The remaining SID units handle various duties, including drug interdiction, training, recruitment, locating fugitives, law enforcement technical support, intelligence, and analytics. SID employs approximately 110 individuals, 87 of whom are sworn law enforcement investigators.

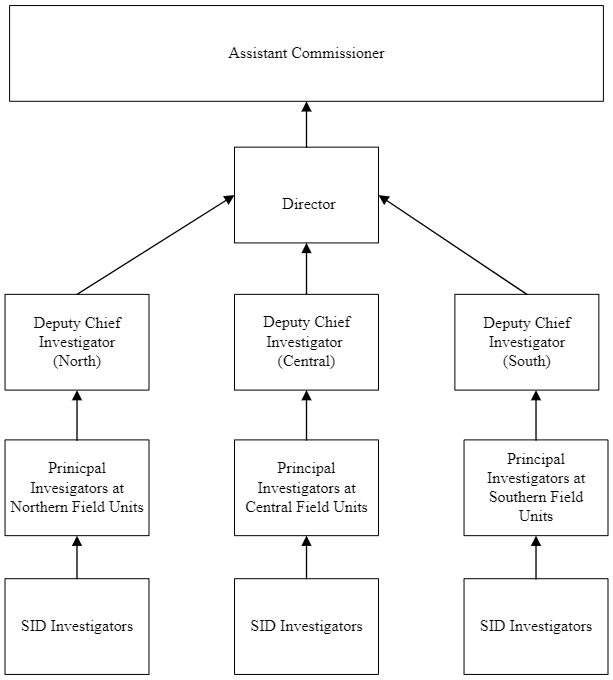

In January 2022, DOC restructured SID’s command structure by dissolving its Chief position and creating a higher-ranked Assistant Commissioner to oversee SID. The Assistant Commissioner-SID reports directly to the Commissioner. According to DOC, the individual serving in this role must be an attorney with experience in the field of criminal justice. In December 2022, DOC created the position of SID Director. This individual reports directly to the Assistant Commissioner-SID. Figure 1 below sets forth SID’s restructured command structure:

Figure 1: SID Command Structure

Each SID investigator is required to attend and complete a basic training course for investigators administered by the Department of Law and Public Safety, Division of Criminal Justice (DCJ). The training covers general topics such as the investigative procedures essential to a successful investigation.

C. SID Policies Governing Investigations

SID relied on three policies that governed its investigations and were in effect during the period of OSC’s review. The first, titled “Investigation Procedures,” effective June 2004, mandated that SID investigations be “professionally, objectively, and expeditiously investigated in order to gather all information necessary to arrive at a proper disposition.” It directed investigators to “examine the initial information available to determine how best to proceed with the case.” The policy listed “considerations” for investigations, including “the witnesses needed, the evidence available, what further evidence should be sought, reports and other records that are available, the order in which witnesses should be interviewed, the technologies needed and whether assistance from any outside agencies might be necessary.” The policy, however, did not provide specific direction or set forth the investigative steps necessary to conduct a complete and thorough investigation.[5]

The second policy, titled “Investigative Interviewing Procedures,” effective February 2015, set administrative procedures for interviews, such as requiring all interviews to be recorded. The policy also detailed when witnesses are allowed to have union or legal representation present during an interview. It did not require specific witness interviews to be conducted or include guidance on interviewing techniques.

The third policy, titled “Investigative Reports,” effective May 1993, established administrative procedures for preparing and submitting investigative reports, such as the appropriate forms to use. The policy did not establish how SID should report its findings or require investigators to recommend a disposition.

D. The Attorney General’s Internal Affairs Policies and Procedures

In 1991, the Attorney General issued the Internal Affairs Policies and Procedures (IAPP), which established statewide rules and standards for internal affairs investigations. In 1996, the Legislature passed a statute requiring all law enforcement agencies to adopt and implement guidelines that are consistent with the IAPP.[6] Since its issuance in 1991, the Attorney General, through directives, has revised the IAPP several times, with the most recent revision in November 2022. However, certain requirements under the IAPP have remained unchanged for over two decades.

The IAPP requires the internal affairs unit of each law enforcement agency to conduct investigations into allegations of serious misconduct, including “criminal activity, excessive force . . . differential treatment, serious rule infractions, and repeated minor rule infractions.”[7]

The IAPP stresses that thorough, objective, and impartial internal affairs investigations of alleged officer misconduct are necessary to maintain public trust in law enforcement officers and equates them in importance to criminal investigations.[8] To that end, the IAPP contains specific requirements to be followed by law enforcement personnel and articulates investigatory best practices for internal inquiries. The IAPP:

- Directs investigators to use any lawful investigative techniques, including inspecting public records such as agency reports, surveillance videos and recordings, and electronic records, interviewing fact witnesses, and interviewing the subject officer.[9]

- Highlights the importance of witness interviews to the investigative process and instructing that investigators should conduct comprehensive investigative interviews, including interviews of the complainant, all witnesses to the matter, and the subject officer, starting with “the complainant and other lay witnesses . . . prior to interviewing sworn members of the agency.”

- Requires investigators to generate investigative reports detailing, in an impartial manner, all relevant facts obtained during the investigation and articulating a recommended disposition for each allegation examined.[10]

- Mandates that investigators prepare a “Summary and Conclusions Report” consisting of a summary of the allegations, a summary of factual findings that outlines the evidence and states a conclusive finding on whether each allegation is to be recorded as exonerated, sustained, not sustained or unfounded, and a section describing any final discipline imposed.[11]

- Directs law enforcement agencies to maintain complete internal affairs investigative files with the investigation’s entire work product, including the investigator’s reports, transcripts of statements, and copies of all documents and materials relevant to the investigation.[12]

Under the Criminal Justice Act of 1970, the Attorney General is designated “the chief law enforcement officer of the State, in order to ensure the uniform and efficient enforcement of the criminal law and the administration of criminal justice throughout the State.”[13] The law requires law enforcement officers to cooperate with and aid the Attorney General in the performance of these duties.[14] In light of these duties, it has been broadly accepted that Attorney General directives like the IAPP have the force of law and are binding on law enforcement agencies such as DOC.[15] However, in historical practice the application of certain law enforcement directives, including the IAPP, to DOC has been uncertain because DOC, and not the Office of the Attorney General (OAG), oversees correctional facilities.

DOC’s Commissioner stated the IAPP has historically been applied to municipal, county, and state police departments, rather than DOC. But she nonetheless shared that she has instructed SID to review the IAPP to determine to what extent DOC can comply. The Assistant Commissioner of SID told OSC that DOC is a law enforcement agency subject to the IAPP, but the Department struggles to apply certain sections of the policy because of its unique jurisdiction. It is unclear whether SID investigators perceived that the IAPP applied to their investigations during the timed period reviewed by OSC.

E. Use of Force in Correctional Facilities

It is well-established that incarcerated people retain their constitutional rights while imprisoned. The United States Supreme Court and New Jersey Supreme Court have recognized that “prison walls do not form a barrier separating prison inmates from the protections of the Constitution.”[16] Therefore, while correctional police officers are authorized to use “non-deadly” force in correctional facilities, such force is only permitted under limited circumstances, and courts have recognized factors that, when present, establish an unconstitutional use of excessive force.

“Non-deadly” force includes both physical and mechanical force.[17] Physical force is defined as “contact with an individual beyond that which is generally utilized to effect a law enforcement objective.”[18] Examples of physical force include “wrestling a resisting individual to the ground, using wrist locks or arm locks, striking with the hands or feet, or other similar methods of hand-to-hand confrontation.”[19] Mechanical force is defined as “the use of some device or substance, other than a firearm, to overcome an individual’s resistance to the exertion of the custody staff member’s authority.”[20] Examples of mechanical force include “the use of a baton or other object, canine physical contact with an individual, or use of a chemical or natural agent spray.”[21]

Physical and mechanical force may be used in a correctional facility in certain enumerated circumstances:

- To protect self or others against the use of unlawful force;

- To protect self and others against death or serious bodily harm;

- To prevent damage to property;

- To prevent escape;

- To prevent or quell a riot or disturbance;

- To prevent a suicide or attempted suicide; and

- To enforce departmental/correctional facility regulations where expressly permitted by NJDOC regulations or in situations where a custody staff member with the rank of Sergeant or above believes that an inmate’s failure to comply constitutes an immediate threat to correctional facility security or personal safety.[22]

Even when the use of force is permissible, correctional police officers may only use the amount of force objectively reasonable under the totality of the circumstances to gain compliance. Officers are required to reduce the degree of force used once an incarcerated person begins to comply.[23] In determining whether force was reasonable, or whether it was excessive, courts consider the following factors: (1) the need for the application of force; (2) the relationship between the need and the amount of force that was used; (3) the extent of the injury inflicted; (4) the extent of the threat to the safety of staff and incarcerated people, as reasonably perceived by the officer using force; and (5) any efforts made to temper the severity of the force.[24]

In 1985, the Attorney General issued a Use of Force Policy, with revisions in 2000 and 2022, applicable to all law enforcement agencies. The 2000 revision, which was applicable during the time period reviewed by OSC, directs law enforcement officers to “exhaust all other reasonable means before resorting to the use of force” and states that “the use of force should never be considered routine.”[25] The policy authorizes the use of non-deadly force when a law enforcement officer reasonably believes force is immediately necessary to (1) overcome resistance directed at the officer or others; (2) to protect the officer, or a third party, from unlawful force; (3) to protect property; or (4) to effect other lawful objectives, such as to make an arrest.[26] The policy also requires all law enforcement agencies to conduct semi-annual use of force training.[27]

The Attorney General revised the Use of Force policy in April 2022 to provide more detailed guidance on the use of force, including the requirement that force must only be used as a last resort.[28] The 2022 policy, in addition to a 2020 Attorney General Law Enforcement Directive, expressly imposes a duty on the officer to attempt to de-escalate the situation before resorting to force.[29] De-escalation is defined in the policy as “the action of communicating verbally or non-verbally in an attempt to reduce, stabilize, or eliminate the immediacy of a threat.”[30]

Prior to 2022, the Use of Force policies did not specifically list DOC as a law enforcement agency bound by the policy, although arguably, as discussed above, the earlier Use of Force policies were always binding on DOC. However, the Use of Force policy was revised in 2022 to specifically include DOC, stating that “[e]very law enforcement and prosecuting agency operating under the authority of the laws of the state of New Jersey, including the New Jersey Department of Corrections and county correctional institutions, shall implement or adopt policies consistent” with the policy.[31]

Since at least 2004, DOC has implemented its own use of force policy.[32] The policy in place during the large majority of the time period reviewed by OSC—revised in 2009 and again in 2019—made it clear that correctional police officers may only use force that is “objectively reasonable and necessary.” Importantly, the policy provides that “the utmost restraint should be exercised and the use of force never considered routine.” Most recently, DOC revised its Use of Force Policy in August 2022 following the release of the Attorney General’s 2022 Use of Force policy. DOC’s 2022 Use of Force Policy incorporates the Attorney General’s 2022 Use of Force policy and specifically states that force shall only be used as a last resort. It also imposes a duty to de-escalate before using force. DOC’s regulations controlling use of force, however, have not been revised since the release of the Attorney General’s 2022 Use of Force policy.

Detailed procedures for implementation of this policy are outlined in a separate Internal Management Procedure (IMP) that has been in place since 2006. The IMPs in place during the relevant time period reviewed by OSC state that correctional police officers may only use force that is objectively reasonable under the totality of the circumstances, and may only use the amount of force necessary to accomplish the law enforcement objective. Those IMPs state that the degree of force must be reduced “as soon as the individual submits.” However, OSC was informed that DOC’s training on the use of force consists of a supervisor reading the Attorney General’s Use of Force Policy.

Methodology

OSC commenced its investigation into SID’s processes and practices following receipt of complaints alleging that SID’s investigations and record-keeping practices were inadequate. In particular, OSC received complaints alleging SID investigators (1) failed to interview individuals who submitted allegations of excessive force and (2) failed to properly maintain evidence of investigations involving officer misconduct.

To conduct this investigation, OSC examined a 20 percent sampling of SID investigative files from cases involving allegations of assault, the use of excessive force, and violations of Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) by DOC staff against incarcerated people at three DOC prisons—New Jersey State Prison (NJSP), East Jersey State Prison (EJSP), and Bayside State Prison (Bayside)—from January 2018 until August 2022. In examining the investigative files, OSC viewed all available video of the incidents. OSC also viewed recorded interviews of complainants, witnesses, and subjects of the investigation and reviewed all documentation contained in the investigative files, including special custody reports, use of force reports, and medical records. Further, if documentation was identified in an investigative report, but not contained in the file provided by DOC, OSC specifically requested that information from DOC. In addition, OSC reviewed all applicable statutes, regulations, Attorney General directives, and SID policies.

OSC staff conducted 18 interviews with DOC personnel, including the Commissioner, Assistant Commissioner of Operations, the Assistant Commissioner of SID, the administrators of two correctional facilities, the Director of SID, the Deputy Chief of SID, two principal investigators, and a senior investigator. OSC also interviewed two correctional police officers who were the subject of excessive force complaints. During the course of their respective interviews, both officers exercised their right against self-incrimination under the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution when presented with questions about their respective uses of force. In addition, OSC interviewed the incarcerated person involved in Bayside Incident 1.

OSC sent a discussion draft of this Report to DOC to provide it with an opportunity to comment on the facts and issues identified during this investigation.

In its response, DOC stated “this NJDOC Administration unequivocally condemns the use of excessive force and employs a zero-tolerance approach to ensure safety, sexual safety, dignity, and rehabilitation for the population.” DOC also stated that beginning in June 2021, it mandated and instituted a number of reforms to remedy the deficiencies uncovered during OSC’s investigation and improve the way in which SID handles accusations of excessive force. This report discusses those specific reforms below, where appropriate.

Investigative Findings

OSC’s investigation uncovered deficiencies in the thoroughness and objectivity of some of the SID investigations sampled, including a failure to interview all witnesses, failure to objectively interview witnesses, failure to include recommended dispositions in investigative reports, and failure to properly maintain SID files. These deficiencies prevented full and fair investigations, especially in those cases that resulted in a decision not to formally discipline the subject officer.

Two SID investigations, in particular, stand as examples of the harms resulting from improper investigations. In both cases, the available evidence strongly suggested that the correctional police officers’ use of force was unjustified and SID’s investigations into those matters were deficient. In turn, what clearly appear to be instances of excessive force by the correctional police officers were not thoroughly and objectively investigated, and the correctional police officers were not disciplined.

A. OSC’s Review of the Available Evidence in the Sample of SID Files Revealed Two Likely Incidents of Excessive Force at Bayside State Prison

OSC’s review of SID case files identified two instances in which it appears that correctional police officers used excessive force against an incarcerated person. Both incidents were captured by surveillance video. The surveillance videos do not appear to show the incarcerated people exhibiting any physically threatening behavior before or at the time force was used. Both officers, however, stated that the incarcerated people involved in those incidents allegedly failed to comply with orders and made verbal threats. The surveillance videos that captured these incidents do not contain audio.

OSC’s review of the videos determined that both officers appear to have unnecessarily escalated each situation and used inappropriate force against incarcerated people.

1. Bayside Incident 1

In 2019, a correctional police officer punched an incarcerated person in the face multiple times and wrestled him to the ground without any visible provocation.

Surveillance video of the incident shows that the incarcerated person was wearing a lanyard around his neck, which is not permissible under DOC policy. The video shows the incarcerated person standing in front of a security desk, on the proper side of the designated “security line,”[33] speaking to someone at the desk who is not initially visible in the frame. The incarcerated person then removes the lanyard from his neck. The video shows him continuing to speak with the person at the desk for a few more moments.

Then, the person at the desk—the subject officer—walks from behind the desk and into camera view. The subject officer crosses the security line, walks up to the incarcerated person, and stands directly in front of him. The incarcerated person steps back from the officer and creates space between the two, but the officer, again, steps in closer to him. The two continue to talk in close proximity to each other. The officer then punches the incarcerated person in the head three times and wrestles him to the ground. A second officer then walks up from behind the desk and into camera view. The second officer assists the subject officer in restraining the incarcerated person. During this interaction, another individual, who appears to be a civilian, can be seen standing in a doorway witnessing the entire encounter.

The video does not show the incarcerated person displaying any type of physically threatening behavior justifying the use of force. The video shows that the incarcerated person did not raise his hands at any point—they remained palms up and at waist-level throughout the interaction. Rather than attempt to de-escalate the situation, the subject officer moved toward the incarcerated person, who took a step back. The subject officer then stepped closer to the incarcerated person and punched him, using so much force that the two ended up on the other side of the room at the end of the incident. The incarcerated person did not fight back after he was first punched, meaning there was no justification for any continued use of force. During the encounter, the subject officer broke his hand and was placed on medical leave for approximately seven months.

In both a written report and in the officer’s interview with an SID investigator, the subject officer claimed that his use of physical force was justified because the incarcerated person verbally threatened him. The subject officer stated the incarcerated person appeared agitated, raised his hands while speaking to him, and said, “when I give [the lanyard] to you I'm gonna have to punch you in your face.” The video does not contain audio to corroborate that such a threat was made, but shows the officer initiating physical contact that is disproportionate to the incarcerated person’s alleged verbal statements. The officer consistently moved closer to the incarcerated person, including by stepping over the security line. Rather than stepping away from the incarcerated person after the alleged verbal threats, the officer stepped toward him and punched him multiple times before wrestling him to the ground.

2. Bayside Incident 2

The second use of force involved an officer spraying Oleoresin Capsicum (OC), commonly referred to as “pepper spray,” in an incarcerated person’s face without any apparent provocation or justification.

Surveillance video of this 2018 incident shows the subject officer and incarcerated person conversing in a common area of the facility’s housing unit. The subject officer is sitting behind the security desk, while the incarcerated person is standing behind the security line talking to him. The incarcerated person never crosses the security line or approaches the desk. During the conversation, the subject officer suddenly stands up, pepper sprays the incarcerated person, and tackles him to the ground. The incarcerated person was looking away from the subject officer at the time he was sprayed.

In both a written report and during an interview with SID investigators, the subject officer claimed the incarcerated person verbally threatened him. He said the incarcerated person was recently disciplined for failing to obey an officer’s instructions and was required to perform extra cleaning duties that day. The officer stated the incarcerated person began complaining about the extra work, at which point the officer ordered the incarcerated person to return to his cell. According to the officer, the incarcerated person responded, “no I’m not going anywhere, but over there to beat your [expletive].”

The subject officer told SID he pepper sprayed the incarcerated person because he felt threatened. The video, however, does not show the incarcerated person motioning towards the correctional police officer or the security desk, or otherwise demonstrating physical aggression towards the officer before the officer deployed the OC spray. During the entire incident, there was a desk between the officer and the incarcerated person. Furthermore, a second officer seen on the surveillance video sitting at the desk next to the subject officer remained seated and writing in a notebook throughout the entire incident. The second officer did not react in any way to the incident, such as by looking up when the alleged threat was made, which appears to contradict the subject officer’s claim that he was threatened and thus justified in using physical force.

B. In Both Cases Identified by OSC, the Inmate Faced Disciplinary Charges While the Officer Did Not Face Any Disciplinary Action

In both incidents, the subject officers claimed that their respective uses of force were justified because the incarcerated people allegedly made verbal threats. This led to disciplinary charges for threatening against both incarcerated people, who then had to proceed through a disciplinary process. Most of the charges were dismissed by hearing officers for insufficient evidence, which suggests the hearing officers did not believe the subject officers’ statements.

DOC regulations identify specific prohibited acts, the violation of which can result in disciplinary charges against an incarcerated person.[34] The regulations require that a finding of guilt at a disciplinary hearing must be based on substantial credible evidence that the incarcerated person committed the act.[35]

As a result of the first incident in which the subject officer punched and wrestled the inmate to the ground, the incarcerated person received three disciplinary charges: (1) threatening, (2) conduct which disrupts, and (3) refusing to obey an order. At the disciplinary hearing, a hearing officer dismissed the threatening and conduct which disrupts charges, but found the incarcerated person guilty of refusing to obey an order based on the allegation that he refused to give the lanyard to the officer. The incarcerated person was sanctioned to 30 days administrative segregation[36] and 10 days loss of recreation privileges.

The hearing officer’s dismissal of the threatening charge, in particular, indicates that the hearing officer found the officer’s testimony to be not credible based on the evidence or to be otherwise unreliable. The disciplinary adjudication form indicated that the hearing officer dismissed that charge for lack of evidence after watching the surveillance video and finding that the incarcerated person had not threatened the officer.

As a result of the second incident, the SID report notes that the incarcerated person received disciplinary charges of (1) threatening, (2) conduct which disrupts, and (3) refusing a work assignment. OSC was informed that these disciplinary charges were subsequently dismissed, meaning there was insufficient evidence that the incarcerated person had threatened the officer and indicating that the hearing officer did not credit the officer’s version of events.

Neither officer received any type of disciplinary action as a result of their respective uses of force.[37]

The Attorney General’s 2022 Use of Force policy imposes an affirmative duty on every officer to report any improper use of force. While not applicable at the time of this review, DOC should extend this affirmative duty to hearing officers who, as in the Bayside cases, find insufficient evidence to support an officer’s statement offered to justify the use of force. In cases like this, simply dismissing the disciplinary charges against the incarcerated person based on a finding that undermines an officer’s justification of force fails to hold the officer accountable for a probable use of excessive force.

C. SID Failed to Interview Eyewitnesses in 22 Percent of its Investigations into Allegations of Excessive Force, Including the Bayside Incidents

SID investigators are tasked with obtaining all information necessary to conduct a thorough, objective, and impartial investigation. Identifying and interviewing individuals who were involved in or observed the relevant events is a basic step in any investigation, which is why the IAPP directs internal investigators to interview all witnesses to an incident.[38]

Overall, OSC reviewed a sample of 46 SID investigative files and found that the investigator failed to interview critical witnesses in 10 of those cases, representing 22 percent of files reviewed. In eight of those cases, the SID investigator failed to interview a correctional police officer who was either assisting the subject of the investigation or located in immediate proximity to the incident. In another case, the SID investigator failed to interview a correctional police officer and civilian who observed the incident. In the remaining case, neither the subject officer nor correctional police officers who observed the incident were interviewed. Figure 2 below identifies the allegations submitted to SID and the eyewitnesses who were not interviewed.

The failure of an investigator to interview all witnesses calls into question the thoroughness, accuracy, and integrity of investigations regarding officer misconduct. Without obtaining statements from all relevant witnesses, an inquiry may only provide a partial picture of an incident and leave potentially incriminating or exculpatory evidence uncovered.

In both Bayside incidents discussed above, OSC found that SID failed to interview key eyewitnesses and that SID’s interview of the subject officer in the first incident was not objective or impartial.

Figure 2: Witnesses Not Interviewed in Reviewed SID Files

|

Facility |

Allegation |

Witness(es) Not Interviewed |

|

Bayside |

Incarcerated person alleged that a correctional police officer (CO) assaulted him without any apparent provocation (Bayside Incident 1). |

A CO and unidentified individual who witnessed the incident were not interviewed. |

|

Bayside |

Incarcerated person alleged that a CO engaged in excessive force by deploying pepper spray without any justification (Bayside Incident 2). |

A CO stationed at a security desk with the subject officer was not interviewed. |

|

Bayside |

Incarcerated person alleged that a CO assaulted and verbally harassed him while being transported between facilities. |

A CO who was present during the transport was on leave during the course of the investigation. That CO was never interviewed. |

|

NJSP |

Incarcerated person alleged that a CO threw him against a fence and forced him to the ground during a transport between facilities. |

A CO who assisted with the transport was not interviewed.

|

|

Bayside |

Incarcerated person alleged that a CO assaulted him during an emergency at the facility. |

A CO who witnessed the alleged incident was not interviewed and a CO sergeant who may have witnessed the incident was not interviewed. |

|

NJSP |

Incarcerated person alleged that a CO inappropriately touched him during a pat-search. |

A CO who was present in the area of the alleged incident was not interviewed. |

|

Bayside |

Incarcerated person alleged that a CO brought him to a location that could not be captured by the facility’s surveillance system and physically assaulted him. |

Two COs who were identified by a witness as being present during the incident were not interviewed. A CO sergeant who allegedly was told about the incident was not interviewed. |

|

Bayside |

Incarcerated person alleged that a nurse inappropriately touched him during a medical examination. |

Two CO’s who were present during the medical examination were not interviewed. |

|

Bayside |

Incarcerated person alleged that a CO inappropriately touched him in violation of PREA during an escort. |

The CO who assisted with the escort and was present at the time of the incident was not interviewed. |

|

Bayside |

Incarcerated person alleged that a CO assaulted him during an emergency at the facility. |

A CO sergeant and multiple other CO’s who witnessed the alleged incident were not interviewed. |

1. SID’s Investigation into Bayside Incident 1

As detailed above, in the first incident, the officer alleged that force was necessary because the incarcerated person failed to obey an order and made verbal threats to the officer’s safety. However, SID investigators did not interview the second officer on the scene or a civilian eyewitness, both of whom could have corroborated either the subject officer’s or the incarcerated person’s account and shed light on whether the use of force was appropriate.[39] The SID investigator later acknowledged in an interview with OSC that the video did not show any visible threats against the officer by the incarcerated person, and that his failure to interview key witnesses was improper and inconsistent with investigative best practices:

Q: Looking back at this [investigation], do you feel those subjects were—could have been important witnesses?

A: Absolutely.

Q: To properly investigate the incident that was captured on this video, should all those witnesses have been interviewed? Would that be proper practice?

A: That would be proper practice, yes.

Further, the investigator’s interview of the subject officer raises concerns that the investigation was not objective and impartial. Instead of asking open-ended questions and allowing the witness to answer, the investigator largely asked leading questions that provided the officer with a justification for his actions. For example, the interview proceeded as follows:

Q: Did he -- I believe [the incarcerated person] verbally threatened you, didn’t he?

A: Yes.

* * *

Q: Alright. Okay, and at the time when he said he was going to, you know, punch you in the face, you obviously perceived this as a threat . . .

A: As a threat.

Q: and you did what you had to do to protect yourself . . .

A: Yes.

Q: . . . and anyone else that was in the area. Do you recall striking the inmate?

A: Yes.

In addition, the SID investigator failed to review the video of the incident with the subject officer during the interview. The interview lasted approximately eight minutes.

In an interview with OSC, the SID investigator admitted that his interview of the subject officer was flawed. He acknowledged that he should not have asked leading questions and should have allowed the subject officer the opportunity to complete the answer.[40] The investigator confirmed that he failed to ask a number of questions that would have provided material critical to the investigation and disposition of the incident, including asking the correctional police officer whether he felt threatened, why the officer proceeded to step closer to the inmate if he felt threatened, and why the officer proceeded to step beyond the security line intended to protect the officer.

The investigator’s failure to conduct an objective interview of the subject officer, his failure to probe the readily apparent inconsistency between the video and the officer’s account, and his failure to interview the two other witnesses resulted in a one-sided and incomplete account of the incident.

2. SID’s Investigation into Bayside Incident 2

Similarly, in the second incident, the investigator inexplicably failed to interview the second officer who was seated next to the subject officer and could have heard any threats made by the incarcerated person. The only materials in the investigative file from the second officer were two brief Special Custody Reports the officer completed after the incident. Neither of these reports, however, contained details about the incident. One report stated that the officer called an emergency code due to the inmate’s actions but did not provide a description of the incident or the incarcerated person’s actions. The other report stated only that the officer called an emergency code.

Both the assigned investigator and his supervisor at the time admitted that the investigation was deficient because the investigator did not interview the second officer. The investigator acknowledged that an interview with the second officer would have assisted in gauging whether the incarcerated person threatened the subject officer, a line of questioning that could have helped evaluate whether force was justified. The investigator could not provide an explanation for his failure to interview the second officer. The supervisor concurred, and stated, “[the second officer] should have been interviewed. I mean, she was there.” The supervisor also stated that the investigator should have “known better” and that the conduct of the investigation was inadequate.

D. SID Failed to Recommend Dispositions Regarding the Allegations of Excessive Force

Requiring recommended dispositions helps ensure that thorough investigations are conducted by compelling investigators to gather sufficient evidence to support their finding that an allegation is “substantiated” or “unsubstantiated.”

The importance of this practice is emphasized by the IAPP, which requires internal affairs investigators to provide agency decision-makers with an investigative report that includes recommended dispositions (sustained, unfounded, exonerated, or not sustained based on the evidence) for each allegation based on the facts disclosed by the investigation. PREA, too, requires investigators to recommend a finding that the allegation was substantiated, unsubstantiated, or unfounded.

OSC’s review of the 46 SID investigative files found that SID investigators did not consistently include recommended dispositions in their respective reports. Overall, 31 of the sample SID files contained recommended dispositions, while 15 did not, including the investigative reports for the two Bayside incidents. OSC found that 20 of the 32 cases that did contain a recommended disposition arose under PREA, indicating that SID generally only makes recommended dispositions when required by federal law. SID’s investigative reports of the Bayside incidents did not include any recommended disposition or finding of whether the allegations of excessive force were substantiated, or, if unsubstantiated, why SID was unable to verify the claims.

SID management advised OSC that SID does not make recommended dispositions because the Division’s role is limited to gathering all relevant evidence so that the appropriate DOC official can make an informed decision on discipline. In the case of administrative misconduct involving officers, the civilian administrator of the prison facility renders a decision. Two prison administrators confirmed that the decision to issue discipline in officer misconduct cases rests with them, with input from DOC’s Office of Employee Relations.

However, limiting SID’s role to simply gathering relevant evidence for DOC’s administration leads to reports that appear perfunctory and often fail to paint a comprehensive and accurate picture that would allow civilian administrators to appreciate the seriousness of the allegations. This effectively diminishes the facility administrator’s ability to exercise oversight. For example, in the Bayside investigations, the SID reports simply contain summaries of the incarcerated persons’ and subject officers’ conflicting stories. In the first Bayside incident, the report does not analyze, or even summarize, the surveillance video, which clearly shows the officer escalating the situation. It is unclear from the report whether the investigator, like the hearing officer in that case, watched the video and also determined that the incarcerated person had not made a threat. In the absence of a thoroughly documented investigative file, it is unlikely DOC administrators can make informed decisions regarding the serious issue of officer misconduct.

E. SID Failed to Adequately Preserve Key Evidence

OSC’s investigation revealed that SID failed to preserve key evidence in 6 of the 46 SID investigations reviewed by OSC. In three of the files, SID was unable to locate recorded interviews conducted during the investigation, including interviews of the incarcerated person and the subject officer. In the other three files, SID was unable to locate the surveillance video of the incident. Figure 3 below identifies the evidence missing from the SID case file reviewed by OSC.

Figure 3: Missing Evidence in Reviewed SID Files

|

Facility |

Allegation |

Missing Evidence |

|

Bayside |

Incarcerated person alleges that he was verbally harassed and touched in a sexual manner while being strip-searched. Subject officers denied allegation. |

The recording of the subject officer’s interview. |

|

Bayside |

Incarcerated person alleges excessive force following a pat search request that resulted in the CO using OC spray. |

The recording of the incarcerated person’s interview. |

|

Bayside |

Incarcerated person alleges a CO took him out of view of the surveillance camera and slapped and punched him in the face. Two COs deny the incident occurred; three incarcerated people corroborated that it occurred. |

The surveillance video from the area. |

|

NJSP |

Incarcerated person alleges a CO inappropriately touched him during a pat frisk. |

Surveillance video referenced in the SID report.

|

|

NJSP |

Incarcerated person alleges he was assaulted by staff while being kept in isolation unit due to suicide risk. Surveillance video did not support allegations. |

The recorded interview of a subject officer. |

|

NJSP |

Incarcerated person alleges that COs poured wax on him while he was sleeping and sexually assaulted him. |

Missing surveillance video referenced in SID report. |

OSC’s request for the complete SID files revealed issues in DOC’s file maintenance practices. Several files originally produced by DOC referenced evidence that was not in the files provided to OSC. OSC sent subsequent requests seeking the missing evidence. DOC initially advised OSC it was unable to locate certain evidence. But, in a subsequent interview, SID personnel stated they later discovered some of the missing evidence on external hard drives that investigators used during the investigations, and provided it to OSC.

The internal affairs process of law enforcement agencies must be designed to instill confidence in the public that allegations of officer misconduct are taken seriously, and that the disposition of those allegations are the result of a thorough, objective, and fair process. Failure to maintain key evidence undermines oversight and raises doubts in the minds of the public that investigations into alleged police misconduct were conducted with integrity. This is of particular importance when the matters involve allegations of excessive force.

The proper retention of evidence such as the recorded statements of complainants, accused officers, witnesses, surveillance video, and other video recordings is also vital to any investigation. By not properly maintaining its evidence, DOC could significantly hamper itself in defending civil lawsuits and prevent an accurate accounting of events in the event that SID’s files are audited.

Proper maintenance of evidence is also crucial for review and oversight by SID management. To that point, DOC advised that in August 2022, the Commissioner and the Assistant Commissioner-SID instituted an internal audit program intended to “improv[e] operations.” Under this new program, senior SID management examines, among other things, the status of open investigations, the proper documentation of evidence in logbooks, and the three most recently completed investigative files at the time of the audit. SID senior management reviews the investigative files to determine whether the investigation was “thorough, unbiased, complete, and credible.”

Although the internal audit program is a step in the right direction, the limited nature of the investigative file review may limit the efficacy of the program. In examining only three investigative files, SID senior management may curtail its ability to identify troubling trends and uncover incidents similar to Bayside 1 and Bayside 2. As such, SID senior management should expand the internal audit program to include a separate review of a greater number of investigative files across a larger time period, and scrutinize additional investigative files from investigators whose performances were found to be deficient.

The internal audit program will also benefit from inclusion of personnel from the Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson (OCO). Tasked with providing independent prison oversight to protect the safety, health, and well-being of incarcerated people, OCO is uniquely qualified to provide valuable insight and expertise. The inclusion of OCO will add an additional layer of objectivity to the process. As such, DOC should coordinate its audit activity with OCO. In so doing, the two entities should memorialize the coordination in a memorandum of understanding that, among other things, sets forth an audit schedule and requires DOC to provide OCO with copies of the documents and materials to be reviewed at least one week in advance of each audit.

F. OSC Identified Three Factors that Contributed to SID’s Deficient Investigations

SID’s failure to interview witnesses, include recommended dispositions in investigative reports, and properly maintain evidence can likely be resolved by DOC’s full implementation of the IAPP. However, OSC’s investigation revealed three additional factors that may have contributed to SID’s investigative deficiencies: (1) law enforcement’s code-of-silence culture; (2) lack of direction in SID policies and procedures; and (3) inadequate training of SID investigators.

1. Law Enforcement Culture

The tendency of correctional police officers to protect each other and the belief that they will not participate honestly in investigations very likely contributed to SID’s failure to interview critical witnesses. During this investigation, an SID investigator articulated this concern when asked why he failed to interview an officer who witnessed an incident involving the use of force. The investigator expressed a sense of futility, stating that correctional police officers “like to stick to each other’s stories.”

OSC questioned two additional SID personnel on this issue. Both personnel denied a wide-spread law enforcement culture of officers protecting each other, and stated that whether an officer will engage in that type of behavior depends on the individual officer. Both personnel candidly provided examples of investigations in which SID found that an officer lied in a statement to cover for another officer’s misconduct. They explained that in those examples, SID had additional evidence to disprove the officers’ stories and uncover the truth. However, they explained that in some cases, even if the investigator has a hunch that officers are lying, SID cannot prove it without additional evidence.

Another SID investigator, on the other hand, acknowledged that this issue does exist, and told OSC that it is SID’s responsibility to “root that out” and discover the truth. He explained that it is possible to penetrate this barrier through proper interviewing techniques and provided examples of lines of questioning he uses in his own investigations when he believes an officer is being untruthful or evasive.

Whether widespread or not, it is well-documented that some police officers will protect their colleagues by not reporting misconduct. This reality should not prevent SID from interviewing all available witnesses, including correctional police officers. Rather, this tendency justifies increased vigilance and highlights the importance of thorough investigations. SID investigators must interview all eyewitnesses, scrutinize all available video of the incident, exercise a heightened level of professional skepticism, and ask incisive questions that effectively probe the subject officer’s version of events.

DOC and SID can also take immediate and proactive steps to address this problem. Footage provided by body-worn cameras may help overcome a culture in which correctional police officers may stick to each other’s stories by providing investigators with additional perspectives of an incident. These cameras allow for an electronic audio and video recording of incidents that take place during the performance of official law enforcement duties. These cameras are particularly important for an investigator examining a matter that occurred outside the view of a prison’s surveillance system. In its response, DOC advised that as of early 2024, all correctional police officers who interact with incarcerated people have been fully outfitted with body-worn cameras.

SID’s ability to conduct arm’s length, independent investigations may also be compromised by DOC’s practice of selecting SID investigators exclusively from the population of correctional police officers. Hiring at least some non-correctional police officers to serve as SID investigators and rotating officers between facilities may improve the quality and objectivity of the investigations. DOC should also consult with other agencies and offices that have experience, and are charged, with the independent oversight of police officers, including OAG, OCO, and the DOJ.

2. SID’s Policies and Procedures Governing Investigations are Inadequate

The SID internal policies on investigative procedures applicable during OSC’s review period did not provide comprehensive direction on how to conduct investigations or how to maintain evidence, resulting in a grant of broad discretion to SID investigators.

SID’s policy on “Investigation Procedures” was revised in December 2023, with approval from DOJ. However, the version of the policy governing SID investigations during OSC’s review period did not provide specific direction or set forth required investigative steps to conduct a complete and thorough investigation—such as a requirement to interview any witness that can be seen in video footage of an incident. Rather, the policy provided investigators with vague guidance and wide discretion in conducting investigations, stating SID investigators should “examine the initial information available to determine how best to proceed with the case.” According to the policy, “considerations include the witnesses needed, the evidence available, what further evidence should be sought, reports and other records that are available, the order in which witnesses should be interviewed, the technologies needed and whether assistance from any outside agencies might be necessary.”

While the SID policy did not articulate a specific process for conducting investigations, two principal investigators explained that the process generally followed by an investigator should include interviewing all individuals involved in the incident and any witnesses. During an exchange about investigative best practices, one principal investigator told OSC, “[I]f someone was identified from a video, you’d make every effort to interview them.” Yet, in both Bayside investigations, key witnesses seen on the videos were not interviewed. The inconsistency between what individual SID investigators identified as best practices and OSC’s findings highlights the need for clear, comprehensive policies.

SID policies regarding maintenance of evidence applicable during OSC’s review period do not contain specific instructions or guidelines detailing the evidence that investigators must maintain in the investigative files. Interviews with SID management, however, confirmed that investigators are taught to retain all evidence obtained during the investigation in the investigative file, including all documents, interview videos, and surveillance videos.[41] According to SID personnel, if surveillance video exists, the investigator is expected to download it in the appropriate format and retain it in the investigative file. One SID supervisor indicated that, in addition to keeping a copy of the video in the investigative file, the investigator should also download it to a separate external drive for a backup. But, again, OSC found investigation files in which the evidence was not properly preserved.

The absence of formal direction on investigative steps and the maintenance of investigative files in DOC policies likely contributed to the deficiencies identified by OSC. During OSC’s investigation—specifically, in March 2024—the Assistant Commissioner-SID instituted a Directive addressing the maintenance of investigative files. The new Directive states that evidence must be properly logged and stored to maintain legally sufficient chain-of-custody. However, additional detailed policies are still needed to minimize variation and promote quality investigations through consistent implementation of processes and procedures. A detailed policy will also set expectations and provide a mechanism for accountability if investigators fail to conduct thorough, objective, and impartial investigations.

During this investigation, DOC, for its part, advised OSC that it is in the process of drafting a policy governing “Investigations of Officer Misconduct,” but that the Department requires “guidance from [OAG] on certain provisions contained in the IAPP.” OSC recommends that DOC expedite the finalization of its policy, and that it include mandatory investigatory and evidence retention practices.

SID investigators and supervisors may have also benefitted from checklists that identified the investigative steps and materials to be maintained in the file, similar to the checklist issued by DOJ for PREA investigations.[42] The use of these checklists can help investigators prepare and plan for an investigation, protect against the unwarranted exercise of discretion, and ensure that the investigative file contains all necessary materials. Checklists would also support SID management’s oversight of investigators.

In its response to a draft of this report, DOC advised that in May 2023, the Assistant Commissioner-SID and SID Director finalized an investigative checklist for use by SID investigators and supervisors to ensure specific steps have been taken to complete a thorough investigation. The checklist is also designed to ensure that outside law enforcement agencies are notified when appropriate.

The creation of the checklist is a positive development. The checklist, however, will only be effective if routinely used by SID investigators and supervisors. SID investigators must use the checklist in planning and executing investigative activities. Likewise, SID supervisors should review investigative files against the checklists to ensure that staff are conducting thorough and objective investigations. DOC would benefit from a written policy requiring routine use of the checklist by investigators and supervisors. Checklists alone, without effective oversight of SID by DOC and OCO, are unlikely to result in sustained reform.

3. Lack of Post-Academy and In-Service Training for SID Personnel

Prior to 2023, SID had not adopted a formal post-academy training program specific to investigating internal affairs matters or an annual in-service training program. Individuals chosen to become SID investigators attend a five-month training course administered by DCJ prior to joining SID. The training includes, among other things, courses on report writing, interviewing techniques, and use of force. Following graduation from DCJ training, SID investigators also historically attended a two-week training administered by SID that largely covered the function of its different units. That program did not train the new investigators on techniques and tactics specific to internal affairs investigations. Further demonstrating the lack of clarity around implementation of the IAPP, a senior investigator explained that investigators do not receive any training on that directive.

Rather, new investigators learn investigative techniques specific to internal affairs investigations by shadowing experienced investigators as they perform various investigative tasks. One principal investigator explained the on-the-job training as ad hoc in nature, indicating that he attended certain functions in order to “see how [the process] works.” SID supervisors also described a similar on-the-job training process for principal investigators. In particular, principal investigators told OSC that they did not receive any formal supervisory training. Instead, they learned how to perform supervisory duties from principal investigators with whom they worked. A supervisor also spoke in favor of a formal training process, stating “the more training the better.”

Shadow training is only as effective as the investigator being shadowed and can lead to inconsistent training among new investigators. This type of training assumes that an experienced investigator is both a good investigator and an effective teacher, neither of which may be true. Without clear direction through formalized training, a new investigator may adopt bad habits displayed by the training investigator.

A lack of a formalized post-academy and annual in-service training programs likely contributed to the deficiencies identified in this report. Although SID investigators learn certain investigative techniques at the DCJ course and by shadowing more experienced investigators, SID investigators would benefit from additional formal training specific to SID’s internal investigations that includes topics such as the receipt and review of officer misconduct complaints, interviewing law enforcement personnel, and ethical issues confronting SID investigators. Likewise, annual supervisory training that focused on, among other things, the completion of investigative steps and a review of investigative files would also help prevent the deficiencies identified above from reoccurring.

The current DOC administration has recognized that the lack of ongoing training for SID principals and investigators is a serious issue. To address this concern, DOC created a Training and Recruitment Unit specifically for SID personnel in March 2023. SID managers advised that SID has special needs that require training other than what is required by the Attorney General. The Training Unit’s primary function will be to find or create training to address those needs. As an example, SID officials stated that in the past a senior investigator would not receive any supervisory training after their promotion to principal investigator. Now, through the Training Unit, all new principals will receive supervisory and leadership training. In its response, DOC advised that supervisors are scheduled for a seven-day training session through the unit in spring 2024. This training will address specific issues relating to their supervision of an SID unit.

The creation of a training unit is a positive and necessary change. In adopting and implementing new training protocols, DOC should create training programs for newly appointed investigators and new principal investigators, and implement an annual in-service training program for all investigators. To ensure the training addresses the deficiencies identified in this report, the training programs must include discussions on identifying witnesses, conducting comprehensive interviews with fact witnesses and investigative subjects, obtaining and maintaining evidence, current developments and trends, report writing, and ethics. It is also necessary that the training instruct SID personnel on overcoming culture that leads to a code of silence in law enforcement and the steps necessary to conduct a comprehensive investigation.

G. DOC Should Seek Guidance from OAG on Application of Certain Portions of the IAPP

Although DOC told OSC that the IAPP is designed more for municipal, county, and state police departments, rather than DOC, Department management, nevertheless, instructed SID to review the IAPP to determine to what extent DOC can comply. DOC advised it might not be able to implement select portions of the IAPP because of the unique environment of prison facilities and the role of SID in conducting investigations at those facilities. In particular, DOC stated that the IAPP’s requirement that an investigator recommend dispositions of “sustained,” “not sustained,” “exonerated,” and “unfounded” differ from the requirement of PREA, which requires an investigator to use the similar, yet different terms of “substantiated,” “unsubstantiated,” or “unfounded.” DOC stated that it also requires guidance on the IAPP’s requirement that an internal affairs unit generate two reports, one of which requires recommendations on discipline, because DOC’s administrators and its Office of Employee Relations, as opposed to SID, are tasked with that responsibility. Lastly, DOC raised the concern that allowing officers to bring a recording device to an investigative interview—something the IAPP expressly permits—may violate DOC’s regulations. DOC advised that it recently renewed contact with OAG to resolve these issues.

OSC recommends that DOC continue to resolve any issues concerning the application of the IAPP with OAG. When those issues are resolved, DOC should memorialize any permitted deviations in policy that, like the IAPP, is made public.

It is important to note that DOC has not asserted an inability to comply with two of the deficiencies identified above: (1) that SID investigators interview all witnesses to an incident in order to conduct thorough, objective, and impartial investigations and (2) that SID preserve all relevant evidence in its investigative case files. Thus, while DOC is working with OAG on the issues above, it can take immediate steps to ensure that those two issues are remedied.

Recommendations and Referral

As noted above, DOC has taken several steps to address some of the deficiencies OSC identified herein, but more must be done to fully remedy those deficiencies. OSC recommends the following:

- DOC should re-open and reexamine the two incidents of apparent excessive force at Bayside identified in this report. In doing so, DOC should ensure that all witnesses seen on the surveillance videos are identified and interviewed, and that the subject officers are properly and objectively re-interviewed. At the conclusion of the investigations, DOC should institute any appropriate employee discipline and refer and share any evidence with prosecutorial authorities as appropriate.

As part of this reexamination, DOC also should review the conduct and performance of the SID investigators who conducted the investigations into the two incidents and their supervisor(s) to determine whether any discipline or re-training is warranted.

- DOC should formulate comprehensive policies, procedures, and/or regulations to standardize its SID investigations and, at the same time, implement the IAPP as fully as practicable. It is critical to both DOC and the public that DOC and OAG promptly resolve any issues with DOC’s ability to fully implement the IAPP. Any deviations from the IAPP approved by OAG should be memorialized by DOC and incorporated into their relevant policies and/or rulemaking. DOC’s policy implementing the IAPP and creating uniform standards for SID investigations should be made readily available to the public, and all SID investigators should be retrained on proper application of the IAPP. DOC should work expeditiously to resolve these issues.

- DOC should engage an independent monitor to examine SID’s case files to determine if the deficiencies identified in this report, as well as other deficiencies, are present in other facilities operated by DOC.

- Because correctional police officers are sworn law enforcement, DOC should accept, as a policy matter, that all Attorney General law enforcement directives are presumptively applicable to it. In doing so, DOC should conduct a comprehensive review to ensure it is in compliance with all such directives and that its policies and regulations are in alignment with the Attorney General’s directives. To the extent DOC determines certain aspects of these directives are impracticable as to DOC operations, it should seek legal advice from OAG and address those issues in a manner that is transparent to incarcerated people, their families, and the public.

- DOC should expeditiously engage in rulemaking to update its regulations to expressly incorporate the Attorney General’s revised Use of Force Policy. In an effort to ensure that correctional police officer misconduct is addressed, DOC’s new rules should also require hearing officers to report instances of excessive force observed during their reviews.

- DOC should create and implement an independent, objective, and comprehensive oversight program to ensure that the investigative deficiencies identified in this investigation are remedied. To that end, SID management advised that it adopted and implemented an internal audit program in August 2022. Although the implementation of that program is a positive initial step, the internal audit program should be strengthened and expanded. SID management should consider expanding the internal audit program to include a separate review of a greater number of investigative files across a larger time period, and a review of additional investigative files from investigators whose performance was found to be deficient.

The internal audit program will also benefit from participation of personnel from OCO. OCO may provide valuable insight and expertise, and add an additional layer of objectivity to the process. DOC and OCO should memorialize OCO’s participation in the audit program in a memorandum of understanding that, among other things, sets forth the audit schedule and requires DOC to provide OCO with copies of the files to be examined with sufficient time to allow OCO to fully review each file and prepare questions. The results of each audit should be memorialized and preserved.

In addition to the audit program, DOC should implement oversight procedures that include, but are not limited to, a mechanism to receive and review anonymous tips, frequent and regularly scheduled oversight meetings, and regular reporting of investigative activity by SID’s principal investigators to SID senior management.

- DOC’s training practices for newly appointed investigators and new principals have created a risk that the deficiencies identified in this report will be perpetuated. DOC, for its part, created the SID Training and Recruitment Unit in March 2023 to provide for improved training of SID staff. To ensure that its new training protocols protect against the deficiencies identified in this report, DOC should consult and coordinate with DCJ and the Police Training Commission to continue to build out its new training protocols. These protocols should include training programs for newly appointed investigators and new principal investigators. The SID Training and Recruitment Unit should also implement an annual in-service training program for all investigators. In addition to topics specific to their roles, all training programs should include discussions on identifying witnesses, conducting comprehensive interviews with fact witnesses and investigative subjects, obtaining and maintaining evidence, current trends in correctional investigations, report writing, and ethics. To be fully effective and address the issues identified in this report, the training must also instruct SID personnel on overcoming the culture within law enforcement that results in a code of silence and the steps necessary to conduct a comprehensive investigation.

- The use of checklists can help SID investigators prepare and plan for an investigation, protect against the unwarranted exercise of discretion, and ensure that investigative files contain all necessary materials. Checklists can also support SID management’s oversight of investigators. DOC advised that it finalized and adopted an investigative checklist to ensure specific steps are taken to complete a thorough investigation. DOC should take all necessary steps, including drafting policies, to ensure that investigators use the checklist to plan and execute each investigative step and that SID management uses the checklists as oversight tools to confirm investigators have conducted thorough and objective investigations.

- DOC should open its SID investigator recruitment efforts to other sworn law enforcement officers who do not serve as correctional police officers, and consider rotating existing investigators among different facilities. A combination of investigators with DOC experience and non-DOC investigators may ensure organizational specific knowledge is preserved while also bolstering the independence of investigators and, by extension, the internal affairs process. DOC, as necessary, should work with the Department of Labor and Workforce Development, Civil Service Commission, to determine the proper title for such employees and to draft a job description that eliminates any requirements that result in investigators coming exclusively from the ranks of those they are charged with investigating.

- DOC should enact policies for the review of SID files and decisions to refer matters for prosecution that memorialize what decisions were made, why they were made, and by whom they were made.

- Transparency regarding law enforcement internal affairs investigations is necessary to foster strong community relationships and public trust. As such, DOC should provide transparency to the public about its complaint management processes. To that end, DOC should include on its website a description of the internal affairs complaint management process and instructions to incarcerated people, or anyone on their behalf, on how to file a complaint. DOC should also post on its website the number of complaints SID has received in the prior year, the categories of those complaints, the dispositions of those complaints, and any corrective actions implemented as a result of those complaints.

OSC will refer the findings of this investigation to OCO. N.J.S.A. 52:27EE-28(a) permits OCO to accept, respond to, and resolve complaints received from governmental agencies, such as OSC. As such, OSC is referring the findings identified in this report to OCO so it can monitor SID’s compliance with the IAPP and its own internal policies; review SID files to ensure that the investigations are thorough, objective, and impartial; and take any other action it deems warranted.

Footnotes

[1] N.J.S.A. 52:27EE-26 to -28.6.

[2] See N.J.S.A. 2A:154-4. The legislative history for this statute, amended in 2017, shows that it was designed as part of a broader statutory scheme to confirm the law enforcement powers that were already held by state correctional police officers.

[3] DOC’s recruitment website encourages individuals to “[j]oin the ranks of the largest law enforcement agency in New Jersey, working to improve safety in our communities.” State of New Jersey, Department of Corrections, Correctional Police Officer Recruitment, https://www.nj.gov/corrections/OfficerRecruitment/

pages/index.shtml (last visited January 5, 2024).

[4] The SVU unit is a specialty unit within SID possessing expertise in sexual abuse investigations. The unit is comprised of one supervisor and eight investigators who, according to DOC, receive frequent, particularized, and relevant training in sexual abuse investigations. This unit was created in June 2022.

[5] As discussed in Section IV(F)(2) below, this policy was amended and finalized with DOJ approval in December 2023.