Delaware • New Jersey • Pennsylvania

New York • United States of America

The Delaware River and its tributaries provide water for many different purposes:

- Drinking Water Supply

- Industrial Needs

- Power Generation

- Water Quality Maintenance

- In-Stream Flow Needs - for aquatic life and recreation (e.g., fishing & boating)

There are no dams on the mainstem Delaware River. There are reservoirs on its tributaries that are used for a variety of purposes: drinking water, water supply, flood mitigation and/or recreation.

The Flexible Flow Management Program, approved by the decree parties (Del., N.Y., N.J., Pa. and NYC) in October 2017, is the current flow management plan for the Delaware River Basin. Learn more about the FFMP and the decree parties below.

DRBC's Flow Management Program

- Ensures that there is enough water in the Basin for all competing needs during normal conditions and especially in times of drought

- Manages water stored in reservoirs that can be released during dry periods to bolster flow levels and/or help repel salinity in the Delaware Estuary to protect drinking water supplies

- Implements Drought Operating Plans that are based on available storage in several Basin reservoirs

- Works with multiple government, NGO, academia and other stakeholders on flow management in the Basin

- Performs modeling and other analyses, in particular to study flows and salinity in the Basin

DRBC's use of science, adaptation and collaboration demonstrates its leadership to build knowledge and consensus, as well as seek creative, win-win solutions to water resource challenges. Planning for future water needs will be coordinated with the decree parties and Basin stakeholders.

See Also

Conflict in the Upper Delaware

The Catskill Mountain region of the upper Delaware River Basin is approximately 100 miles from the New York City metropolitan area. Back in the early 1900s, New York City was aware that the upper Delaware watershed was an excellent source of high quality water, and was interested in accessing that water for the city.

But, the Delaware River does not flow into New York City, as New York City is not in the Delaware River Basin. Instead, the headwaters of the Delaware River drain to New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware, supplying water to numerous down Basin communities, including the Philadelphia metropolitan area.

In addition to drinking water, the Delaware provides valuable habitat and is an outstanding recreational resource.

These multiple demands have led to intense competition for the waters of the Delaware.

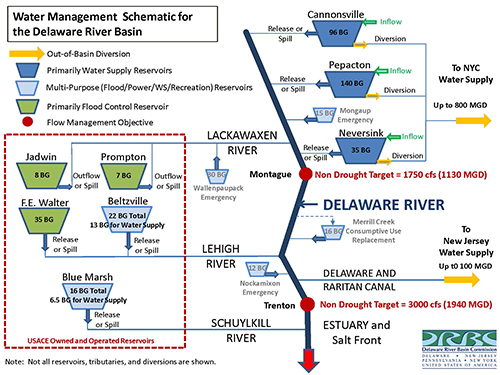

Today, New York City obtains more than half of its water supply from three major reservoirs in the upper Delaware River Basin: Cannonsville, Pepacton and Neversink. This all started with a lawsuit between states, State of New Jersey v. the State of New York and New York City.

1931 & 1954 U.S. Supreme Court Cases

When one state sues another state, original jurisdiction lies in the U.S. Supreme Court. A lawsuit between states is one of the few instances in which the U.S. Supreme Court hears a case that has not come up through the trial and appellate courts.

In this particular instance, there were five parties before the U.S. Supreme Court – the four basin states (Del., N.J., N.Y., and Pa.) and New York City. These are the decree parties.

On May 4, 1931, the United States Supreme Court issued a decree authorizing New York City to divert an average of up to 440 million gallons of water per day (mgd) from the Delaware River Basin to its water supply system in the Hudson River Basin. The decree was issued to settle the case of the State of New Jersey v. the State of New York and New York City and resolve an interstate dispute over the allocation of water in the basin. The decree required that New York City release sufficient water from its DRB reservoirs to maintain a specified flow in the Delaware River at Port Jervis, N.Y. and at Trenton, N.J.

The 1931 decree was amended on June 7, 1954, establishing an equitable allocation under federal common law that is still in place today. The amended decree established the following terms:

- Allocated to New York City the equivalent of 800 million gallons per day from the city’s three Delaware Basin reservoirs, effective when all three of those reservoirs were fully constructed, which occurred in 1964.

- Required compensating releases to maintain a minimum flow objective of 1,750 cubic feet per second (cfs) at Montague, N.J. (the Montague flow target); eliminated the 1931 minimum flow objectives at Port Jervis, N.Y. and Trenton, N.J.

- Established an Excess Release Quantity to be released from the reservoirs each year; and

- Authorized the state of New Jersey to divert an average of 100 million gallons per day from the Delaware River Basin to the Raritan River Basin through the Delaware and Raritan Canal (D&R Canal).

The amended decree established the chief hydraulic engineer of the U.S. Geological Survey, or that official's designee, as the River Master.

USGS Delaware River Master

The River Master's job is to insure that the provisions of the 1954 decree are met. The daily operations are conducted by the Deputy River Master through a field office of the U.S. Geological Survey in Milford, Pennsylvania. The Deputy River Master reports to the River Master, whose office is located in Reston, Virginia.

The duties of the River Master include the observation, measurement, correlation, interpretation, and reporting necessary to accurately administer the provisions of the 1954 decree. The River Master provides the technical measures by which the implementation of the decree formula for the drainage area upstream of Montague can be judged. The annual River Master report to the Supreme Court provides a detailed daily accounting of all flows and directed releases used to fulfill the decree requirements.

The River Master is also directed by the decree to conserve the waters of the basin. In addition to coordination with New York City, the River Master works with upstream hydro-power generators to determine their release schedules; if they are generating, those planned releases are considered when determining needed releases from NYC's reservoirs. The neutrality of the River Master, as an official of the U.S. Geological Survey, has been an important factor in the administration of the decree provisions.

DRBC's Formation in 1961

Water supply shortages and disputes over the apportionment of the Basin's waters were among the primary reasons that led to the creation of the DRBC in 1961.

The Delaware River Basin Compact (pdf), which is federal law and law in the four basin states, grants the Commission broad powers to plan, develop, conserve, regulate, allocate and manage water resources in the basin.

However, the DRBC's power to allocate the waters of the basin is subject to an important limitation: sections 3.3 and 3.5 of the Compact prohibit the Commission (comprised of the four basin states and the federal government) from adversely affecting the rights and obligations of the parties to the U.S. Supreme Court Decree of 1954 without the unanimous consent of the decree parties (the four basin states and NYC). In other words, the Compact provided the Commission with authority to modify the diversions and releases of the 1954 decree conditioned on the unanimous consent of the five decree parties.

The DRBC has exercised this authority and the decree formulae have been modified on numerous occasions.

DRBC's first important challenge came with multiple years of drought in the 1960s. It became obvious from the 1961-1967 "drought of record" that NYC could not withdrawal 800 mgd and still have enough water for the required compensating releases to the Delaware River to meet the Montague minimum flow objective of 1,750 cfs.

A new operating regime was needed to (1) conserve storage and ensure flow augmentation during a repetition of such conditions, and (2) to address a flow need not recognized by the Supreme Court in 1954 – the need for minimum flows (or "conservation releases") to sustain aquatic life. There were two choices – resort to further litigation or test the value of the DRBC to develop an equitable solution. Luckily, the latter alternative was chosen.

Negotiations began in 1978 and culminated five years later in the Good Faith Recommendations (pdf). Drought management aspects of the 1983 Good Faith Recommendations were included in the DRBC regulations known collectively as the Water Code (pdf), and conservation releases from the NYC Delaware reservoirs for the protection of fisheries were established in a DRBC docket (D-77-20 CP). The decree parties unanimously consented to each of these instruments – the docket and the regulations.

The Trenton Flow Target

The drought management program adopted by the DRBC in 1983 included the establishment of a minimum flow objective at Trenton, N.J. of 3,000 cfs, in addition to the Montague flow target.

DRBC is responsible for meeting this flow target through releases from two Pennsylvania reservoirs owned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Blue Marsh Reservoir (located on the Tulpehocken Creek, a tributary of the Schuylkill River) and Beltzville Reservoir (located on the Pohopoco Creek, a tributary of the Lehigh River). DRBC owns water storage in these two reservoirs for this purpose, which is financed by surface water users under a water charging program implemented by the DRBC.

The Trenton flow objective is intended to ensure that enough freshwater flows into the estuary to repel the salt front, protecting drinking water and industrial intakes in the Delaware Estuary around Philadelphia and Camden.

Storage in Blue Marsh and Beltzville reservoirs is also used to trigger drought warning and drought operations in the Lower Delaware River Basin - that portion of the basin downstream of Montague, N.J. This allows for reductions in the Trenton flow target and the New Jersey diversion when lower basin conditions are drier than in the upper part of the basin. Accordingly, lower basin operations are controlled by both basinwide or lower basin storage triggers, with the most limiting restrictions controlling.

DRBC has taken on the responsibility of meeting the Trenton flow target and has received the cooperation of the River Master in this activity. The River Master has continued to be responsible for administration of the decree provisions for the drainage area upstream of Montague, N.J., and any modifications resulting from the DRBC operating plans.

Flexible Flow Management Program (FFMP)

The mainstem Delaware River is also susceptible to flooding. Three serious main stem Delaware River floods between September 2004 and June 2006 added yet another important management issue for consideration: the potential use of NYC's water supply reservoirs to enhance flood mitigation.

And, these reservoirs are also being studied to see if they can be better managed to enhance fisheries and protect in-stream flow needs.

As such, the decree parties - with hydrologic modeling expertise and facilitation support provided by DRBC staff - have been engaged in a complex, collaborative effort to balance the multiple, sometimes competing uses of NYC's water supply reservoirs while recognizing the rights established by the 1954 decree.

- The most recent Flexible Flow Management Program was approved by the decree parties in October 2017

- DRBC issued a press release recognizing the October 2017 approval

- Implementation Performance Reports for the Flexible Flow Management Program (published once a year by DRBC)

The 2017 FFMP was modified in 2018, amended in 2023 and has an expiration date of May 31, 2028.

Looking ahead, DRBC staff continues to work closely with the decree parties on flow management in the Basin.

Presentations & Webinars

- Building Blocks of Water Resilience: Highlights from the Delaware River Basin Commission (pdf; CDRW conference, Sept. 2024)

- The Flexible Flow Management Program: Effects on the Delaware River Basin (pdf; CDRW conference, Sept. 2023)

- The Flexible Flow Management Program: Effects on the Delaware River Basin (pdf; CDRW webinar, May 2023)

- Basin Wide Cooperation for Drought Resilience: DRB Case Study (pdf; UPenn presentation, March 2023)

- The Science of Flow Management (pdf; WRADRB webinar, 2020)

- A Fishable, Swimmable (and Drinkable) Delaware River Estuary (pdf; Delaware River Watershed Forum, 2020)

- State of the Basin 2019: Flow Management (pdf; 2019)

- History of the Salt Front (pdf; Delaware River Watershed Forum, 2019)

- Flow Management in the Delaware River Basin (pdf; presentation, 2018)

- DRBC Drought Management (pdf; presentation to the WMAC, 2016)

Reports & Resources

- Modernized DSS: A Habitat Model for the Upper Delaware River (NJ, NY, PA) (pdf; report, June 2022)

- Implementation Performance Reports for the Flexible Flow Management Program (updated annually)

- Delaware River Basin Planning Support Tool (DRB-PST): a publicly available tool used by DRBC and stakeholders to examine flow and drought management alternatives

- Hydrology Dashboard: updated daily, highlights key data for flow and drought management in the Delaware River Basin

- R scripts: updated graphics that show water yields for basin subwatersheds, discharge data for the mainstem Delaware and Schuylkill rivers and surface water elevation in the tidal Delaware River

- Water Management Schematic for the Delaware River Basin (pdf)

Copyright © Delaware River Basin Commission,

P.O. Box 7360, West Trenton, NJ 08628-0360

Phone (609)883-9500; Fax (609)883-9522

Thanks to NJ for hosting the DRBC website